Editorial

Since our inaugural issue 0, most editorials have addressed in one way or another what expositions of practice as research are, and what they can be. In many of these editorials, ontological, institutional and also political concerns stood in the foreground, as JAR has worked to navigate and contribute to a field. At the same time, there are also some editorials that focused more on the material making of expositions: JAR3 looked at issues of design as specific distributions of media; JAR6 highlighted the role process can play; JAR8 discussed practices of appropriation etc. We found our feet over these first few years and, since then, some editorials have aimed to draw more specific conclusions about expositionality: JAR11, for instance, called for a ‘fuller image’ in ‘sufficiently complex articulations;’ JAR15 characterized this as emergent mediality; and JAR28 saw in expositions specific, directed relationships between knowns and unknowns.

Looking back, it is striking how language veered towards the abstract the more concrete the phenomena at hand were, in terms of their own, specific modes of sense-making. Of course, this fact should not come as a surprise given how delicate the concrete here is: we can show and understand it in its richness, but we cannot explain it to the same degree. It is as if, in reading an exposition, we must go through at least some of an exposition’s many operations, and to see (or hear!) sense, not only being made for us on a page but also inside us and in our imagination. What does this say about the communicative nature of expositions and the mode audiences are informed of artistic research?

To answer this question, let’s dig into our memory of an exposition we deem valuable. Yes, I may remember its title or the name of the author, but this may often be just a handle, in particular when I link the exposition up with other works. More important than this is the memory of certain moments when I remember an exposition working. These are not directly accessible, even in my memory; rather, time is needed to render active these moments, and this may not happen on a first read or even retrospectively. In some cases, these moments of work just fall into place, in others it can be hard work to get to these points and in others still, despite my best efforts, I feel left out.

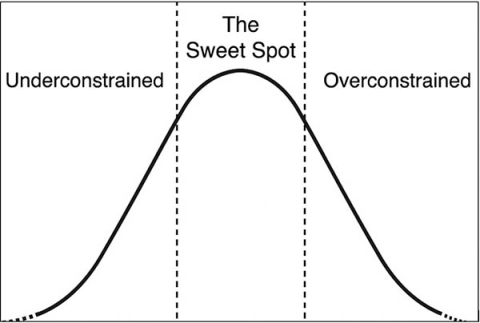

When I say that it takes time, what I actually mean is that I cannot recall straight away the point at which sense is made; rather, I have a vague memory of where it is and what in its proximity is required, but I must see these things connected again to access meaning. Strangely, though, in expositions, things are also connected in other ways, which has the effect that in my memory of an exposition, alongside the connections, I also remember tensions, that suggest at times contradictory modes of reading. Relations are multiple and seemingly changing as points of reference are moved In other words, I remember the meaning of an exposition as a whole as fluctuating, its fabric as plastic.

The strange thing is, that both the screen and my imagination seem often – but not always – able to hold such multiple or even contradictory things, and we could argue that therein lies the whole purpose of expositions: to render possible the holding of complex thought as sharable form. This is, of course, what we usually refer to as reading and writing, but approached through the practice of exposition we highlight both their material and medial dimensions: material, since expositions are made up of concrete things, even on a computer screen; medial, since in expositions these things come together to operate in specific, at times multiple ways.

From these speculations we may derive an explanation why it is so hard and rare that expositions reference other expositions, since a point of reference is not just stable and given. We may also understand that cases of ‘best practice’ cannot easily be listed, since what is best practice must differ from case to case. And we may also understand why in so many cases, we also see fail-safes built into expositions that reduce complexity and increase propositional content. Abstracts, introductions, or contextual sections often work to this end. In fact, we may not yet have seen full examples of expositional referencing or, for that matter, radical expositionality. How would this look like?

Returning to the question of communication, with expositions we don’t just share new meanings and understandings as information about something. Here, information is not content held in a form, but the process by which meaning comes to be held in a form as a mode of its propagation. Implied, though, is that each material context not only links up things differently but also in multiple ways. This creates a setting where the sender and receiver – to maintain those outdated notions – may, after the communicative act, remain interlinked, since the things that I hold, or the thing that I am, may connect in the same way, breaching the confines of what we usually call a message. It would not be too difficult to imagine that all things remain connected in much more fundamental ways, both spatially and temporally.

Michael Schwab

Editor-in-Chief