The ‘True Truths’ in the Research of Artists Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa

Carolina Benavente Morales

In this reflection, I am interested in exploring the role of artistic research in and in response to the so-called post-truth regime. I will address this question through two proposals by Chilean artists: one of them is La memoria en el cuerpo (The Memory in the Body), by Janet Toro (1963), a montage of "performative traces" (Barría, in Toro, 29/09/2023) that revives two works from the nineties around the torture methods used by the Chilean civic-military dictatorship between 1973 and 1990; the other proposal is the Library of Non-History, by Voluspa Jarpa (1971), an installation and relational work from 2010 about declassified archives of the intervention of the United States of America (USA) in the coup d'état that originated this dictatorship, on September 11, 1973. While the visit of Janet Toro's recent exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of Chile motivated me to make this contribution, I decided to add Voluspa Jarpa's proposal after seeing a presentation by the artist on the subject at a seminar of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the same institution. These proposals, which refer to what could be two poles of the fabrication of a Latin American dictatorship and the responses it provokes from contemporary art, also indicate the relevance that artistic research can acquire facing of post-truth, as well as the peculiar configuration it acquires at the local level.

Truth and post-truth in Chile

Toro and Jarpa's artistic proposals involve research practices that coincide in safeguarding the truth of recent historical events. In Chile we are commemorating the 50th anniversary of the civilian-military coup in the midst of denialism unparalleled since the recovery of democracy in 1990. Indeed, doubts have been sown about the human rights violations that have occurred since the coup d'état that overthrew President Salvador Allende and the Popular Unity government (1970-1973), with torture being described as "urban legends." This denialism is linked to recent events. The Constitutional Convention that gave rise to the Social Outbreak of 2019 sought to change the foundations of the neoliberal model established in dictatorship and developed in post-dictatorship through the 1980 Constitution, provoking a disinformation reaction reminiscent of Brexit or the irruption of the Alt-Right1. While these latest events explain the consecration of post-truth as the word of the year 2016, what happened in Chile is more dramatic because there are practically no counterweights to the oligarchic media and even less to the digital platforms controlled from abroad. Thus, even as a result that can also find other factors, the proposal of the Constitutional Convention of 2022 was rejected by 62% of voters. Inflamed by this and other recent electoral successes, some sectors are openly denying or even validating the outrages of the civilian-military regime.

In a previous approach, the situation described had not yet been presented, but somehow it was foreseen. I approached post-truth in order to understand the artistic turn that was taking place in a Chilean interdisciplinary doctorate and in my own academic practice. Although the RAE (2022) defines it as the "distortion of a reality, which manipulates beliefs and emotions in order to influence public opinion and social attitudes", post-truth does not refer so much to these operations, which have always existed, as to a new regime, that is, following Michel Foucault, to a set of procedures and institutions of knowledge-power. For this reason, post-truth also designates an unprecedented era in which, under the influence of digital social networks, social and political relations are reconfigured as citizen expression is favored, but according to immediatist and uncritical modes that threaten democracies. From this point of view, I pointed out the importance of the experiments of truth that, through mutual appropriations of the 'objective' truths of the sciences and the 'subjective' truths of art, take place in the intricacies of the academy. Thus, I outlined an ambiguous space generated by embodied knowledge "where the logical-rational component is conditioned by and also subject to the persuasive-affective procedures that are deployed in the classroom, the academic field, the public space and culture" (Benavente, 2020, 121). On that occasion, I sought to validate as interdisciplinary research competencies some of the ways in which the social sciences and humanities turned to the arts, with post-truth as an epochal background. In this reflection, I am interested in how the confluence of the arts with other disciplines generates devices of knowledge-power aimed at sustaining, updating and disseminating 'true truths'.

I adopt the notion of 'true truths' from the musical Manifesto of Víctor Jara (1974), who created this song in the tense context that would lead to his assassination on September 16, 1973. The expression is not redundant, since truths are statements about the real that are socially constructed, and can acquire different values. In the text mentioned above, I referred to the objective truth of science as a truth "sufficiently proven and recognized as real, but always in function of socially constructed or imposed premises that legitimize the relevance of establishing it" (118-119), which presupposes the action of the communities involved. Víctor Jara's True Truths put before that the political component of making uncomfortable the Truths established by the Powers from an experiential knowledge that, however, can always be controversial. In fact, although erroneous or intentionally false truths are imposed more easily than before in post-truth, the salient phenomenon is that the true is relativized to the point of dissolving into a sea of opinions that are not subject to test or debate. For this reason, they should not be confused with the subjective truths of art, which would involve genuine debates with the self, others and the environment, as well as a validation by the critic – within the complexity of its configuration. But my argument is that, in the post-truth regime, certain artistic initiatives decouple themselves from the mere manifestation of subjective truths, seeking to safeguard the very status of truth through processes of investigation, testing and debate that they take charge of; and that this aspect contributes, among other factors, to understanding the rise of artistic research, if it is understood that research seeks to establish truths, even provisional ones, about matters that arouse curiosity or concern. The concern underlying the search for truth is what would allow us to speak of true truths that maintain an accentuated political and poetic sense, but reinforced in their veracity through the use of research tools.

Truth is a critical topic in the South American Cone countries because, along with justice and reparation, it responds to demands that have been raised in the face of different atrocities perpetrated throughout history in the region. Often used with an initial capital letter, such as "Truth", the term arises from memories of oppression, not from wills to impose; from concrete experiences of repression, not from a mere plane of speculation; and from ongoing traumas to the present day. The demands for truth raised by the direct victims of the politicide carried out by the dictatorial regimes from the 1960s to the 1980s have been extended to include indigenous peoples, women, sex-gender diversities and the environment. In turn, the term 'politicide' is related to genocide, ethnocide, femicide and ecocide, but designates the actions of states that, in Chile and other countries, affected left-wing militants during the Cold War, for the purposes of effective annihilation and terror. More broadly, it has recently been established that the demands for truth, justice and reparation concern the very possibility of living together democratically on the basis of a "civilizational minimum" that is respect for human rights, although from an understanding of the dignity of life that tends to extend them to social and not human rights.

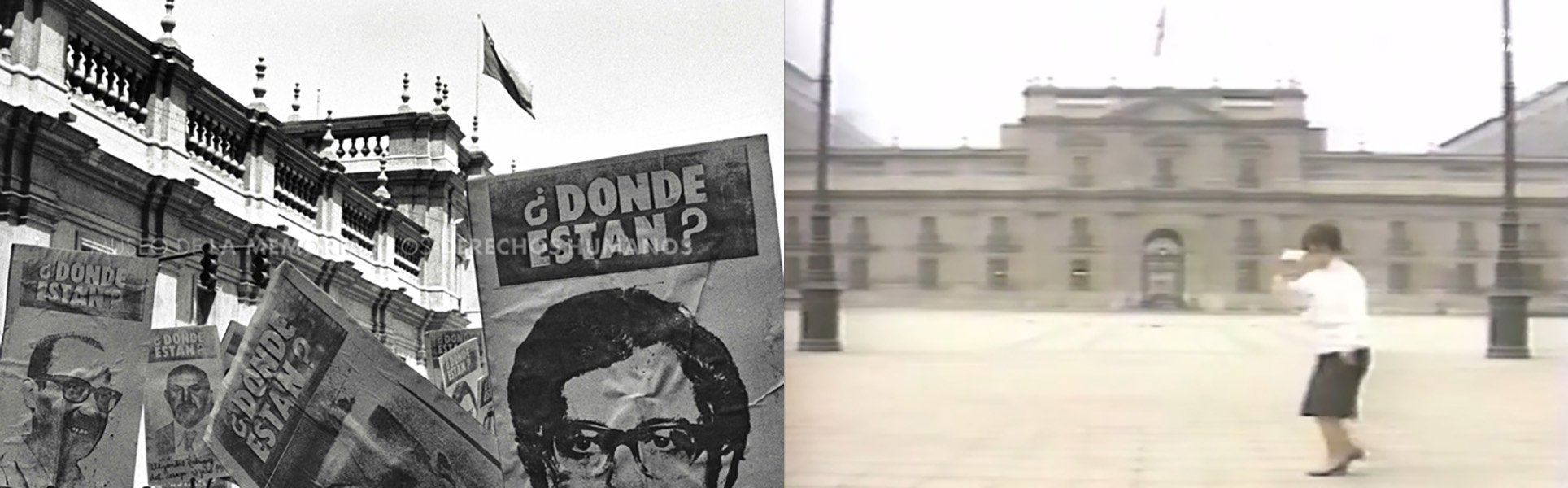

Despite the fact that violations of these rights are unquestionable realities from the point of view of their victims and protectors, their defense on a legal level has been active from the beginning, precisely because of an understanding of the socially constructed nature of the truth, and the need for its political-institutional sanction. The arts have been involved in this process in different ways, renewing their resources according to the contexts. In Chile, the "¿Dónde están?” (“Where are they?")2 poster or the "La cueca sola3" dance —reappropriated in the song "They dance alone", by Sting (1987), or in the performance La conquista de América, by Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis (1989)—, are part of this history of artistic and activist circulation of truth in the 1970s and 1980s, along with many others in those decades and the following. Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa participate in this history in the context of the "supervised" democracy of the post-dictatorship in which practices marginal to artistic institutions began to be welcomed and promoted by them. This evolution is significant, in that it legitimizes the artistic status of eclectic proposals, where creation is imbricated with action according to non-traditional aesthetic and poetic criteria. However, the aspect I wish to outline refers to the parallel and connected evolution of the investigative development of these same proposals, as a way of expanding the conditions for establishing the truth.

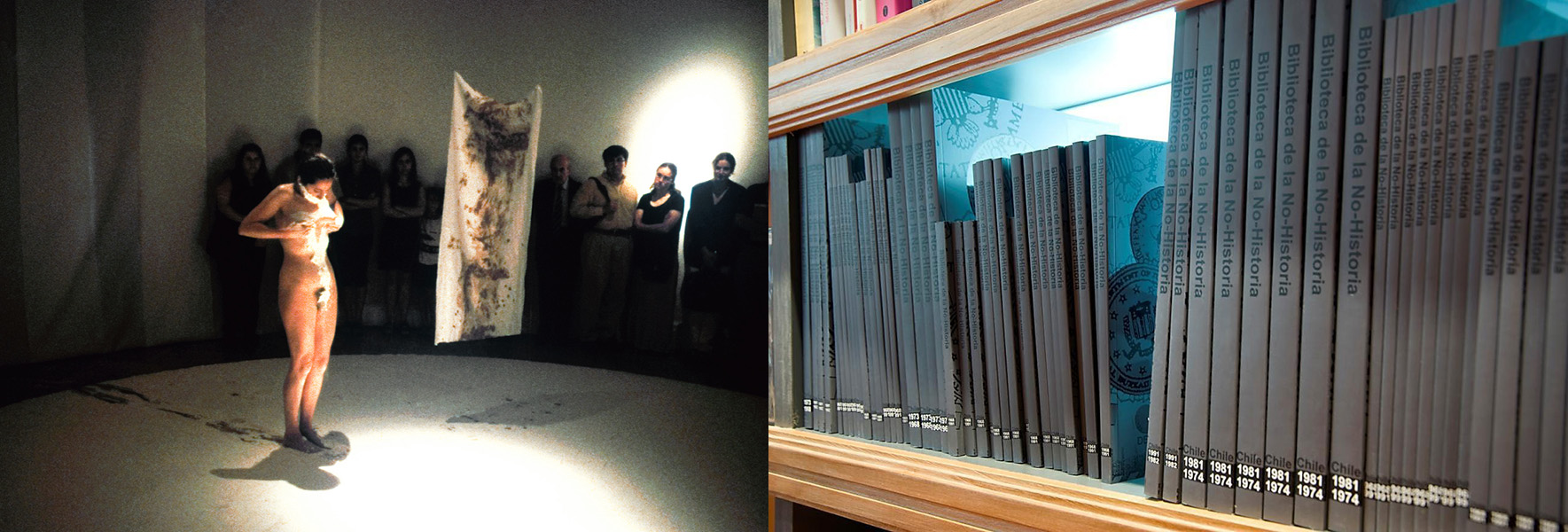

Janet Toro (1963) is a visual and performance artist who participates in different arts and resistance collectives during the dictatorship (1973-1990), after which she continues her work individually and moves to Germany for fifteen years, until returning to Chile in 2014. Her exhibition La memoria en el cuerpo is a reposition of two previous proposals: 1) the performance La sangre, el río y el cuerpo (The Blood, the River and the Body), from 1990, in which she walks with her naked body along an islet of the Mapocho River, impregnating a large white canvas with blood of slaughterhouse animals with which she wraps herself and then lies on the ground – "The most essential thing was my feeling of absolute intensity and veracity", she recalls (in Artishock, 18/09/2023)—; and 2) K (The Body of Memory), presented at the II Biennial of Young Art of the National Museum of Fine Arts in 1999, and consisting of performing the methods of torture used by the dictatorship, for which he uses chalk, flour, the canvas of 1990 and her own body. Her actions take place between the museum and different places of murder, torture and political prison. She points out those places in the public space through marks and poetic inscriptions made during kilometer barefooted walks in which she wears a canvas as a shroud. In 2023, La memoria en el cuerpo dialogues at the MAC with other exhibitions commemorating the 50th anniversary of the coup d'état, inverting in its title the terms of the original exhibition to underline the idea of the body itself as a repository of memory. The body can also be conceived as a support of truth in a biological and affective sense, given that the artist has made explicit her condition as the niece of Enrique Segundo Toro Romero, who was arrested and disappeared from his home on July 10, 1974.

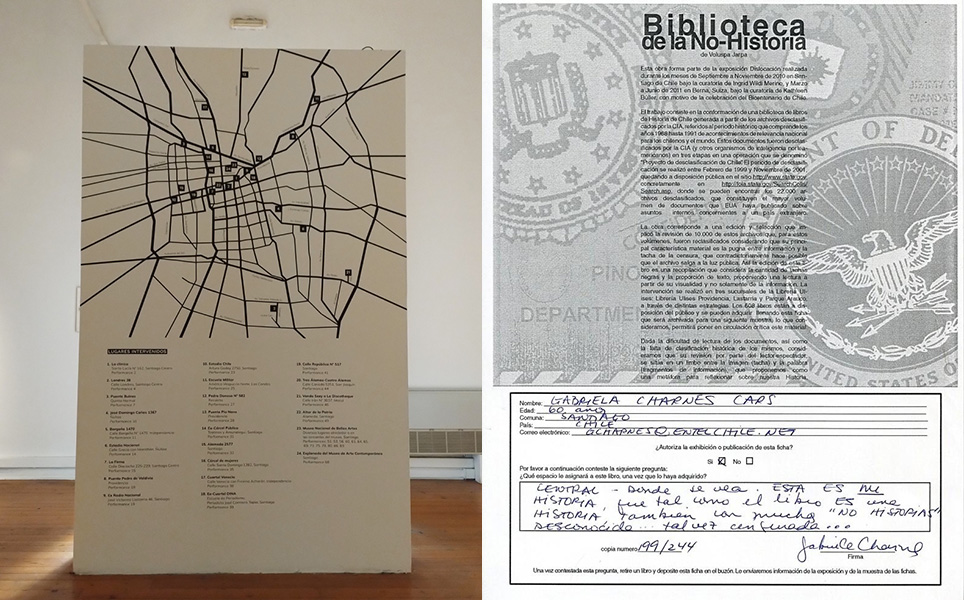

Voluspa Jarpa (1971) shares this memory of oppression, since, after the coup d'état, her family went into exile in Brazil, returning to her native country in 1989 to study arts at the University of Chile (like Toro). Painter, initially, she moved towards other materials and techniques to address the problem of "history as hysteria". The Library of Non-History is a series of exhibitions whose first version was held in different venues of the Ulises Bookstore in 2010, the year of the Bicentennial of Independence, within the framework of the collective exhibition Dislocation (Wildi Merino, 2010). Its axis is the files of the intervention of the CIA and other USA intelligence agencies in the Chilean coup d'état of 1973. The country declassifies them after being pressured to collaborate in the trial of the Chilean dictator captured in London in 1998, at which point Jarpa begins an investigation into the matter that culminates in 2018. In the bookstore, the installation on a shelf of books made from these archives is accompanied by the delivery of copies to the public, in exchange for answering a question on the subject. The following year, Jarpa participated with La no-historia in the Mercosur Biennial of Porto Alegre, pointing out that his exhibition "reveals through the documents and its exhibition device how our national histories have not yet begun to be narrated with the veracity of the events that have occurred" (Jarpa, 2012, 104).4 In 2023, the artist will not remount her exhibition, but will present it at the seminar 50 años: la Unidad Popular interrumpida (50 years: The interrupted Popular Unity)5, organized by the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Chile (FACSO, 23/08/2023).

It can be said that, from a strong socio-political involvement, Janet Toro works around the truth of the violated body in its integrity, while Voluspa Jarpa elaborates the truth of the violated nation-state in its sovereignty. This common search entails the realization of research that must be understood in a loose way, since it is not entirely articulated from the enunciations of the artists, nor do they originate expositional publications similar to those of JAR —for example or notably—. This could be due to a generational factor, since the institutional deployment of artistic research in Chile and, more particularly, its recognition at the doctoral level is little more than a decade old. However, it could also be due to the preferential adoption of what Michael Schwab (2011) designates as "channels" that "amplify" expositionality. But, in spite of this, in this case the amplification is not carried out from an exhibition publication format, but by channeling the research towards different types of collaborations, audiences and spaces; although in a way that is susceptible, in turn, to becoming a publication. What is remarkable, from a cultural point of view, is that the searches of both Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa give rise to configurations where knowledge is generated at the complex intersection of different artistic, political and academic fields, beginning to be made explicit by the artists themselves.

Therefore, it can be thought that the development of the arts as research becomes necessary to contribute to the establishment of truths through a more involved and at the same time a more shared doing. In this work, the enunciation of the artists themselves takes on a relevant role as a basis of support. In fact, although they continue to have the support of critics, theorists and researchers, in accordance with the traditional configuration of knowledge in the artistic field, they begin to engage in a dialogue with them on an equal footing that emancipates them from epistemic subjections and, at the same time, holds them ethically responsible. It is as if the "truth" alluded to in expressions such as "the truth of art" or "the truth of poetry" needs to be underpinned, reducing to a certain extent the polysemy intrinsic to any artistic proposal in order to underline the existence of such a truth, so conceived, so established, one could say, alliterating Foucault when he points out that criticism is the disposition to "not be governed in such a way" (2007, 8). In this way, paradoxically, a more categorical form of truth is reached, since it is a truth that is laid bare in its own mechanisms, exposing and debating even those aspects that are reluctant to be elucidated, to be illuminated; in a poetic-epistemic chiaroscuro that evades both the pretense of clarity of science and the obscurity of post-truth.

From this point of view of artistic research, the task of establishing truths can be approached at different levels. There are different ways of conceiving artistic research in its plurality, but my concern is not to propose a model in this regard or to point out what its phases and characteristics are. In a rather intuitive way, although with some theoretical supports—the development of which exceeds the purpose of this reflective text—I observe parallels between what was carried out by the artists under consideration. These common axes are related to processes of truth-making; truth is its matrix, though imbricated with research. I propose to associate the aforementioned levels with the tasks of research, interpretation and debate: research refers to the collection of data or information related to the issue of concern in its factual dimension, by means of different methodologies; interpretation refers to the organization of both the research and the information gathered through certain perspectives; and debate refers to the sharing of the previous steps, in order to discuss them within a community interested in knowing and, eventually, contributing to the process. At any of its levels, this process may involve the use of artistic methodologies, combined with those of other disciplines.

The artistic investigations of Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa

In both Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa, research is associated with file management. Janet Toro tracks down information about torture in court documents and human rights organizations, as well as in victims' testimonies that she collects. When she carried out this work, there was already a report by the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission or Comisión Rettig (1991),6 which states that 1,068 people were murdered and 957 were detained and disappeared by the dictatorial regime between 1973 and 1990. But it is only the first report of the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture or Comisión Valech (2005)7 that states that there were 9,795 victims of detention and torture, adding 30 additional victims to those of the Rettig Report8. For this reason, Toro anticipates the facts and contributes to raising them, by participating in the creation of a favorable climate for the establishment of a new official truth in this regard. Voluspa Jarpa, for her part, collects the first declassified files of the USA intelligence agencies regarding their intervention in the coup d'état, and she immerses herself in reading them. This intervention was somehow always known, but the declassification allows it to be measured. To this day, there are unknown aspects in this regard, which is why a delegation of USA parliamentarians recently visited Chile to express their willingness to request the declassification of new files.9

Although this work with archives is related to the bureaucratic tasks that, according to Ignacio Irazuzta (2020), are professionalized around the defense of human rights and, in particular, around the searches for the disappeared in Latin America, Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa resort to them with a different intention. This intention can be deduced from the operations they carry out. Regarding the reports that proliferated in the post-dictatorship period, Sergio Rojas states that they involve "a form of necessary relationship with what happened that differs substantially from the narrative (history, testimony, chronicle, etc.)," since they renounce "judging relations of meaning, and then all the elements enter a 'foreground' that is a neutral plane" (Rojas, 1999, 242-243). From the above, it can be said that for Toro and Jarpa it is a matter of generating or working around reports to safeguard the truths they contain about "what happened", but seeking to delve into their sensitive and perceptual dimensions to unveil other truths about it. These other truths refer either to the political-bodily affectation referred to in the documents, or to the functioning of the documents themselves that convey the non-history of this affectation. Establishing them involves analytical and interpretative activities in the manner of visual or performance studies, but also and above all concrete processes of artistic creation.

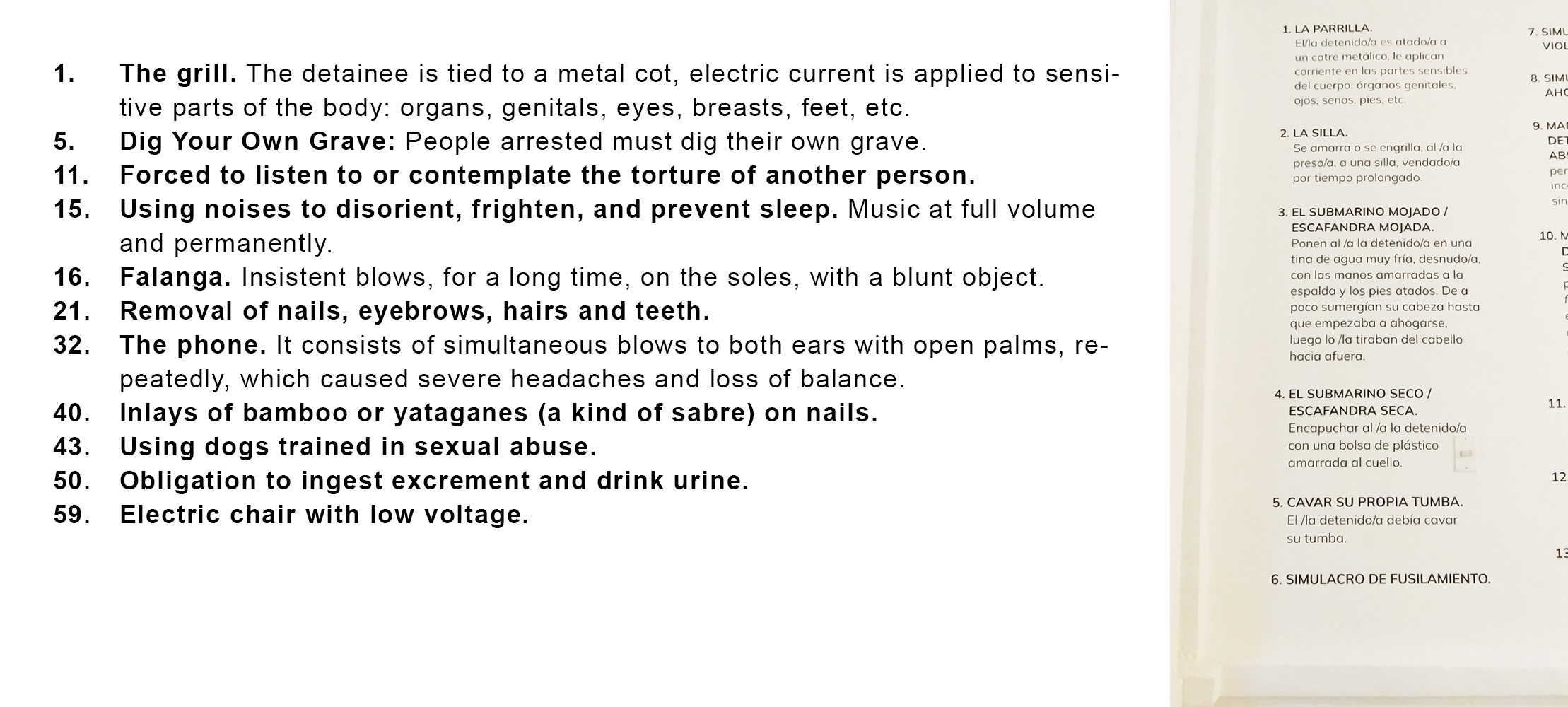

In the case of Janet Toro, the artist examines between the lines the materials collected to establish 62 "physical and psychological methods of torture applied in Chile," as well as some of the sites associated with it in Santiago, Chile. In her recent 2023 exhibition, she lays out a map of these sites and details torture methods. These methods are written on the wall of one of the narrow rooms adjacent to the main rooms, which include photographs, videos, and the canvas of the ninety 1990 and 1999 performances and installations that she made from them. Some of the methods she introduces us to are:

This numbered list of torture methods is a report, but its order seems random, it is not systematized and does not contain explanations. It is not a medical, psychological or legal report. In the Valech report, the methods appear in the description of when and how the victims were imprisoned according to different periods, without details of their name, age, work and militancy, and there is a special section entitled "Methods of torture: definitions and testimonies" (Comisión Valech, 2005). The information is provided mainly by the victims and the case is reconstructed by the officials10 in the "neutral" way pointed out by Rojas. In Janet Toro's artwork, the methods of torture are approached with succinct descriptions that evoke that neutrality but reorient them towards a way of doing with the body. According to the artist, through performance her intention is not to illustrate or represent torture in a "theatrical" way or "through simulations", but to approach it "in a real way", so that on each occasion she lives experiences close to drowning or blindness, among others, which arouse sensations of anguish or pain (Toro, 29/09/2023). The purpose, she suggests, is to "open the folds of the dark memories of that harsh reality, attached to the organism", from the premise that "memory is not only a functional activity of the mind, but a bodily experience: we remember with the body" (Artishock, 19/08/2023). Janet Toro reactivates in the present the suffering of the Chilean body politic, confronting her viewers with the historical, physical and psychic truth of the "shock" (Klein, 2010).

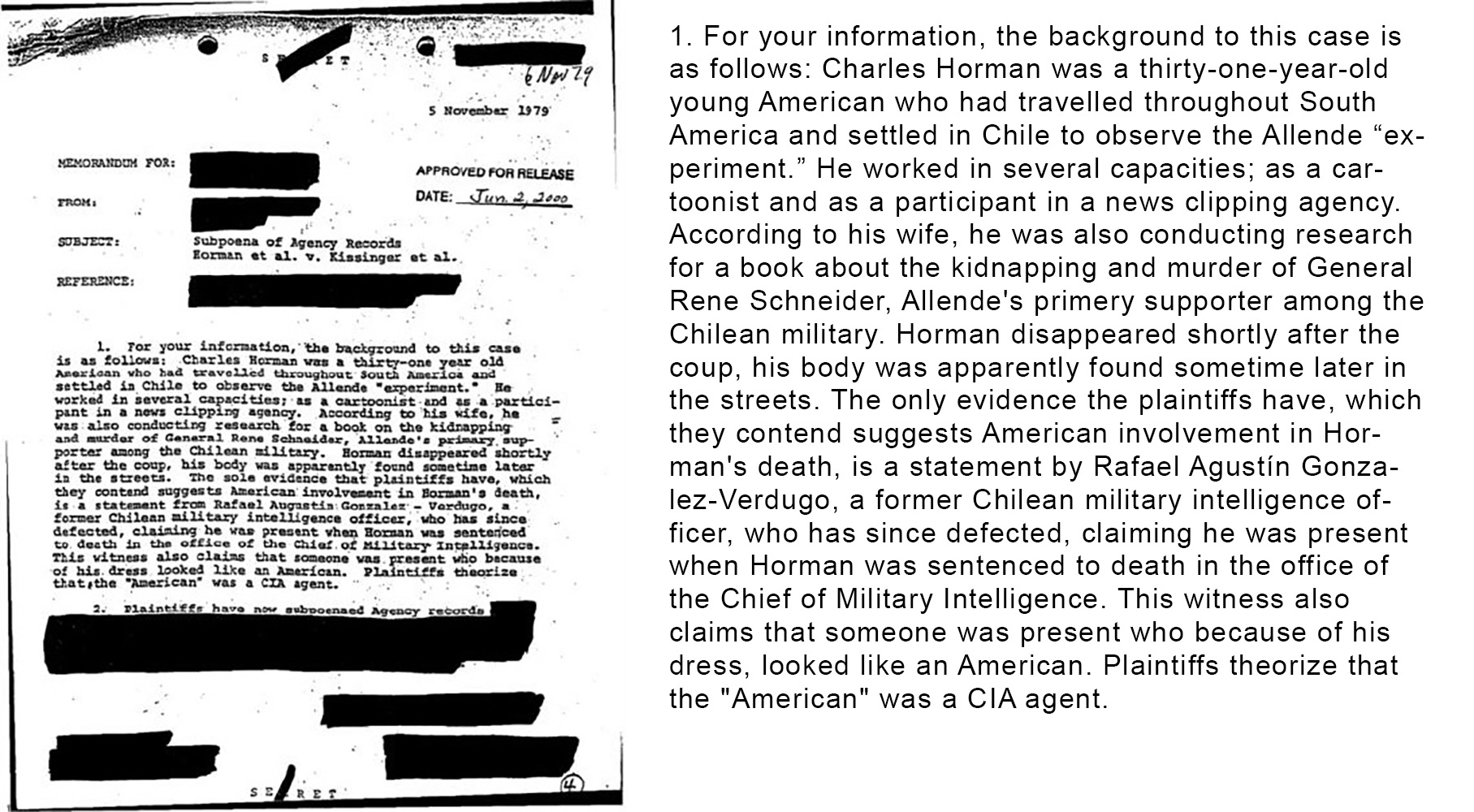

In the same way, when working with declassified CIA documents, Voluspa Jarpa certainly contributes to making visible the truth of the USA intervention in Chile, but her approach and method are not historical, geopolitical or intelligence, without ceasing to resort to these disciplines, since her research on the subject is eminently visual and artistic. Through her Biblioteca de la no-historia, this artist intervenes in the headquarters of the Ulises bookstore through installations and relational actions that interrupt the usual flow of library spaces. Moreover, the conventional bookish device is disturbed by both the exhibition and the delivery of volumes that she conceives as "non-books." Among the ten thousand declassified archives that she reviews to create 608 books of five different types and formats (Jarpa, 2012, 90), the following is counted:

For me, as surely for many people of my generation and those before it, Charles Horman's story is reminiscent of the film Missing, directed by Costa-Gavras (1982), which he did inspire. The selection of this page is no coincidence. However, Voluspa Jarpa stresses that, beyond the content of the CIA documents, she seeks to question or interrogate the visual modes of operation of this agency in relation to a history of classifications, declassifications, visibilizations, erasures, strikethroughs that unveil the truth in order to continue veiling it: "I could speculate that at first they are texts (documents), back at the origin of their production; however, I might think that once they have been declassified (deleted) and reproduced, they have fallen, perhaps under the regime of the image, or at least, they have remained in an intermediate zone between the two," she reflects, adding that "one sees a fragmented text and the strikethrough of it, but the strikethrough is at the same time a black and abstract figure" (Jarpa, in Tala, 2012, 9-11). Thus, the artist brings to the surface a non-truth that has numerous declensions.

Although the proposals of Toro and Jarpa differ in terms of artistic references and procedures, since the former participates in performance in the manner of Viennese actionism, while in the latter the influence of conceptual art and post-structuralism is noticeable, both converge in an auratization of the bodies erased from history, as well as of the erased body of history itself, seeking to preserve its memories. In El cuerpo de la memoria, Janet Toro sets up a sepulcher space in one of the rooms adjacent to the central exhibition, filling it with dust on the floor through the use of flour, while in the Biblioteca de la no-historia Voluspa Jarpa backlights the shelves of the non-books so that they stand out in the space of the bookstore, in a way that evokes the tombs embedded in the walls of churches and cathedrals. In the silence and seclusion that this sepulchral dimension entails, in its predominantly black and white tones, crossed in red in Janet Toro, both proposals establish a continuity with the experience of violence and death in the dictatorship in Chile. They respond to the still stunned or suffocated context of the post-dictatorship, although in a particular way, which entails a displacement towards the city, towards the urban space, towards non-traditional places of exhibition, looking in the street or the shopping centre for unforeseen or unaccustomed spectators. In this way, they also contribute to Chilean society looking at itself and recognizing itself in a history that many do not know or would like to forget. This restless but controlled post-dictatorship context contrasts with the din of true truths that characterized the Social Outbreak of 2019; A racket silenced, in turn, by the current disinformation and denialist scream of the Chilean far right.

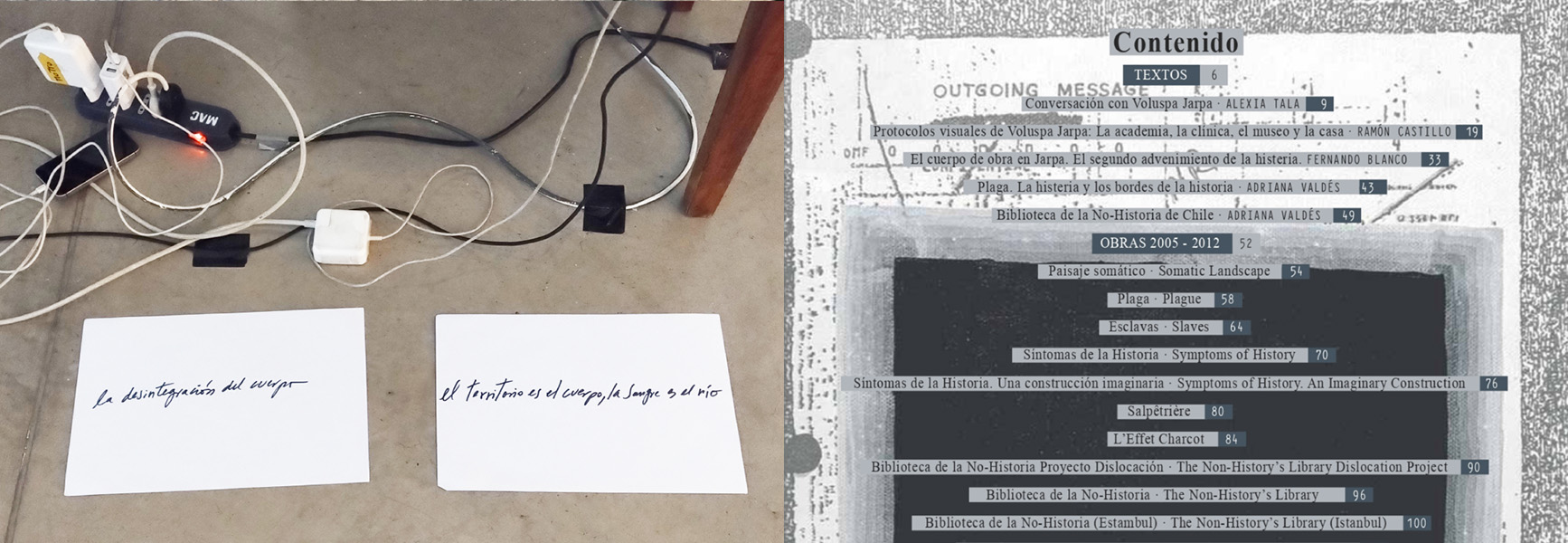

It is in this latter context, however, that an additional level to research and interpretation is best appreciated, which is that of communication and debate of processes and results. This aspect, which seems now fundamental for the social construction of a true truth, is most evident in the production of Voluspa Jarpa. In fact, on the one hand, the file of the question to the public that she uses in Biblioteca de la no-historia (2010) includes the background information about its exhibition and a request for authorization for the publication of the answers. For this reason, it can be said that it constitutes a kind of informed consent form similar to those used in the sciences and, in any case, different from the less formalized (or even parodic) questionnaires that are usually used in the arts. Thus, it can be seen that relational practice is accompanied by a genuine desire to generate knowledge. On the other hand, this artist documents the work she is producing from early, generating textualities about it through descriptions, files, oral or written interviews or, likewise, the publication of books. These books can even have an expository character, depending on how one could conceive of expositionality in JAR in terms of a text-medial or text-visual articulation of the research carried out, as noted in her Historia / Histeria. Obras 2005-2012 dossier (Jarpa, 2012). Now, through these productions that break into the traditional writing work of curators, theorists, and researchers in the field, the artist gives an account of her motivations, problems, perspectives, methods and results in a way that is not so attached to these categories, but quite thoroughly, which responds to the fact that she herself characterizes her processes of production of work as research.

Janet Toro also includes statements on her website and her catalogues of her work, although to a lesser extent. The expositional nature of her proposal can be seen above all in La memoria en el cuerpo, especially through the inclusion of the list of torture methods and the mapping of the sites intervened during her performative tour in 1999. This schematic map corresponds to the city of Santiago and the highlighted points are not random: they indicate the different places near the National Museum of Fine Arts where she made his interventions, but above all those places that functioned as centers of detention, torture and death during the dictatorship and that in recent decades have been converted into sites of memory. In Santiago, they are mainly located in the historic center of the capital, but in some cases the artist took her practice to peripheral sectors, within the great ring delimited by Américo Vespucio Avenue. Because of the information provided by signaling of places, this map is also a kind of special report, which this time has a spatial emphasis. Both through the list of torture methods and through this map, Janet Toro gives additional information to the purely visual or corporeal, providing elements that sustain it, and transform it. This artist also conceives her artistic practice as research, but from the body, as she puts it in response to a question I ask her in one of the conversations held in La memoria en el cuerpo:

Normally I do a lot of research before doing something, I go to the places, I feel the places, I talk to the people who live there, I ask about the history of the place, what happened in that place, all that, before doing a job, I take photos, I make sketches, that is, there is a whole previous work that is hidden, but for me it is fundamental because it also gives consistency to a work. In the later works, as in El cuerpo de la memoria, in the post-dictatorship period, too, the same, only that I integrate much more methodologies and practices of body work, for example, yoga; then also progressive muscle relaxation, eutonia, I am always discovering other methods that allow me to be whole, that also allow me to have a good circulation, have your muscles well prepared for those tremendous walks, and so on. In other words, I also see there a need to know my body deeply, to know its limits, its weaknesses and its capabilities in order to be able to respond in a more comprehensive and also deeper way (Toro, 05/09/2023).

Precisely, where perhaps the participation of both artists in a sphere of research is most noticeable is in their recent participation in forums that involve other disciplines and where they debate about their processes. In the case of Janet Toro, this takes place in two conversations, including the one mentioned, in which theorists Isabel Jara, Sergio Rojas and Paulina Faba, on the first day, and Joselyne Contreras, curator of the exhibition, Mauricio Barría and Paola Nava, producer of the MAC, on the second day, refer to the exhibition. But the artist also elaborates on her production and research processes, and it is interesting to note that the second conversation takes place in one of the rooms of her exhibition, intervening the floor in front of the headboard with handwritten notes on paper referring to her work. In a poetic way, as she did in the public space in her 1999 performance El cuerpo de la memoria, she makes explicit some of the meanings of her proposal, referring in this quote to her 1990 performance La sangre, el río y el cuerpo: "the territory is the body, the blood is the river" (Toro, 29/09/2023).

In the case of Voluspa Jarpa, the interdisciplinary dimension is more accentuated, since she is invited to present her research together with sociologists Alberto Mayol and Rodrigo Baño at the aforementioned Seminario 50 años: la Unidad Popular interrumpida, on August 23, 2023. Along with Jarpa's historical accent and Toro's spatial accent, there is once again an important difference between the conceptual and theoretical approach of the former and the corporal and practical approach of the latter; as well as in a differentiated type of referents of thought and production, which in Jarpa have a rather intellectual and learned character, while in Toro they are preferably part of a social or popular environment. An interesting aspect of Voluspa Jarpa's presentation is the willingness to dialogue that she demonstrates when she alludes to what was raised by the colleague who preceded her, Alberto Mayol, incorporating on several occasions in her own speech some of his ideas, such as those related to truth, the narration of history or communication. For example, she observes the following:

What's interesting when you look at the strikethroughs in that sense, in relation to what you're talking about as the truth, and the truth necessary for the construction of the historical meaning of a society, is that we inevitably have to see ourselves reflected in that colonial or neocolonial fabric where part of the things that we live we don't know, we didn't know, and we probably won't know; and that this is a state of condition of this State and of other States. So, what I find interesting about these strikethroughs is that the strikethroughs are the present, while the text is the past. In other words, the strikethroughs are what I can't read today because it's active, somehow, today. Therefore, it is the present that I cannot see, while that which was transformed into text is that which I can already access because it has already passed. But that chaos of truth and history that is implicit in that document partly reveals some of our problems (Jarpa in FACSO, 23/08/2023, 03:06:03).

In this way, a set of ideas that are usually rather implicit in works today tend not only to be made explicit and shared, but also to interweave with others in the public space through oral and written statements that could come to form a consolidated and expanded corpus of artistic research for truth. For the rest, there are many more presentations that both artists are currently making to new audiences, with other researchers and even in other countries.

To close

Truths are social constructs, so they can or often are the object of socio-political disputes. Today, this dispute is more bitter than ever, endangering the truth itself as an eagerness to get closer to reality. Based on Luc Boltanski, Ignacio Irazuzta (2020) conceives the real as that which comes into the "normal" state of reality, which is why it deserves to be investigated. In the post-factual era that is concomitant with the post-truth regime, however, the facts seem unable to impose a reality, but rather succumb to what, from Maurizio Ferraris (2013), could be called 'realityness'. For this reason, neither scientific, legal nor artistic research, although necessary, seems sufficient. Artistic research can make a difference in these conditions, but one that does not respond only or so much to the subjective and more or less expressive or conceptual component characteristic of art, but also to complex, hybrid, documented and interwoven perspectives and methodologies through which we try to establish and settle truths that break the prejudices, assumptions and preconceptions that distance us from reality. In different ways, with different emphases, the artists Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa participate in a movement in this sense, deploying various operations to safeguard the truth so that true truths do not stop breaking in and circulating.

This leads me to a final thought. In a recent book highlighting the appropriations of Dada art by the Alt-Right, Jack Southern (2023, 303-304) asks, in exploring possible "other" drifts on the part of contemporary art, whether "we are beginning to see the emergence of genuine alternatives—a possible antidote to the proliferation of platforms that prioritize consumption and instant reaction, over sustained thinking, reflection and the progressive distribution of ideas", and proposes that the new citizen platforms should be supported by state and government funds. A not insignificant problem, as we are experiencing in Chile, is that for the post-truth forces it is now a matter of dismantling the state apparatus itself, along with any notion of the public, the common and the social, in order to establish the reign of "everyone for themselves". However, as an idea to be expanded perhaps in the future, it is possible that the surroundings of art itself, combining fictions, metaphors, testimonies, documents, imaginaries and arguments, among others, will today become the privileged place for the elaboration of truth. With its focus on artistic research and the multiple resources it has been developing, could JAR somehow anticipate the platforms to come?

References

Anguita, P., Bachmann, I., Brossi, L., Elórtegui, C., Escobar, MJ., Ibarra, P., Lara, JC., Padilla, F. y Peña, P., (2023). El fenómeno de la desinformación: Revisión de experiencias internacionales y en Chile. Santiago: Comité Asesor contra la Desinformación; Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología, Conocimiento e Innovación.

Artishock (19/08/2023). Janet Toro: la memoria en el cuerpo. Artishock. Revista de arte contemporáneo. https://artishockrevista.com/2023/08/19/janet-toro-la-memoria-en-el-cue…

Barría, Mauricio (29/09/2023). Presentation in a discussion forum. In: Toro, Janet. La memoria en el cuerpo (exhibición 14/07-30/09/2023). Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Parque Forestal, Universidad de Chile.

Benavente Morales, Carolina (2020). El giro artístico del DEI UV: investigación artística y formación doctoral interdisciplinaria. In: Benavente, Carolina, ed. (2020). Coordenadas de la investigación artística: sistema, institución, laboratorio y territorio. Viña del Mar: CENALTES / CIA UV. 105-132.

Comisión Valech (2005). Informe de la Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura (Valech I). Ministerio del Interior, Gobierno de Chile. https://bibliotecadigital.indh.cl/items/77e102d5-e424-4c60-9ff9-70478e6…

Dyk, S. van (2022). Post-Truth, the Future of Democracy and the Public Sphere. Theory, Culture & Society, 39(4), 37-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764221103514

FACSO (23/08/2023). Seminario “50 años: la Unidad Popular interrumpida” (second day). Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Chile. https://www.youtube.com/live/Do_0mTWcr_Y

Ferraris, Maurizio (2013). Manifiesto del nuevo realismo. Siglo XXI.

Foucault, Michel (2007). ¿Qué es la crítica? Sobre la Ilustración (pp. 3-52). Tecnos.

Jara, Víctor (1974). Manifiesto. Manifiesto (álbum 33’’). Castle Music Ltd. https://youtu.be/uj-3mpjDC8M?si=8IgqykkFyVqlrESP

Jarpa, Voluspa (2012). Historia / Histeria. Obras 2005-2012 (dossier). Self-publication / Fondart. https://www.voluspajarpa.com/dossiers/historia-histeria/

Johnson, Andrew (1992). La cueca sola, de la Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desparecidos (AFDD). Threads of hope (Hilos de esperanza) (documentary, fragment). Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos. https://www.facebook.com/MuseodelaMemoriaChile/videos/-la-cueca-sola/53…

Klein, Naomi (2010). La Doctrina del Shock. El auge del capitalismo del desastre. Paidós.

Irazuzta, Ignacio (2020). Buscar como investigar: prácticas de búsqueda en el mundo de la desaparición en México. Sociología y Tecnociencia, 10(1), 94–116. https://revistas.uva.es/index.php/sociotecno/article/view/4222

Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis (12/10/1989). La conquista de América (performance). Comisión Chilena de Derechos Humanos, Santiago, Chile. https://www.yeguasdelapocalipsis.cl/1989-la-conquista-de-america/

RAE (2022). Posverdad. Diccionario de la lengua española. Ed. del Tricentenario, 2022 update. https://dle.rae.es/posverdad

Rojas, Sergio (1999). La visualidad de lo fatal: historia e imagen. Materiales para una historia de la subjetividad (pp. 223-248). La Blanca Montaña.

Sting (1987). They dance alone. Nothing like the sun (album). A&M. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MS_bN5ECJTI&ab_channel=StingVEVO

Schwab, Michael (2011). Editorial. Journal for Artistic Research (1). https://www.jar-online.net/es/issues/0?language=es

Southern, Jack (2023). The Multiple Narratives of Post-Truth Politics, Told Through Pictures. In: Hegenbart, Sarah, & Kölmel, Mara-Johanna (eds.). Dada Data: Contemporary Art Practice in the Era of Post-truth Politics (pp. 292-308). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Alexia Tala (2012). Conversación con Voluspa Jarpa. Entrevista realizada vía e-mail en julio de 2011, con ocasión de la 8a Bienal del Mercosur, Porto Alegre, Brasil. Jarpa, Voluspa. Historia Histeria. Obras 2005-2012. Self-publication / Fondart.

Toro, Janet (29/09/2023). La memoria en el cuerpo (exhibición 14/07-30/09/2023). Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Parque Forestal, Universidad de Chile.

Ugarte, Marco (1983). Palacio presidencial de La Moneda, Santiago (w/b photography). Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos. http://www.archivomuseodelamemoria.cl/index.php/158420;isad

Wildi Merino, Ingrid, cur. (2010). Dislocación (collective exhibition). Santiago de Chile. http://www.dislocacion.cl/

Biographies

Carolina Benavente Morales (Chile, 1971). Experimental researcher in art, literature, and culture, see http://www.therealcarolin.cl/novedades

She holds a Ph.D. in American Studies with a specialization in Thought and Culture from the University of Santiago de Chile, and a Bachelor's degree in History and Political Science from the Catholic University of Chile. She grew up in France and Mexico. She co-organized, alongside Ana Pizarro, África/América: literatura y colonialidad (FCE, 2014), edited Coordenadas de la investigación artística: sistema, institución, laboratorio, territorio (Cenaltes, 2020), and authored Escena Menor. Prácticas artístico-culturales en Chile, 1990-2015 (Cuarto Propio, 2018). She co-founded and directed Panambí. Revista de investigaciones artísticas and the Centro de Investigaciones Artísticas (CIA-UV) at the University of Valparaíso (2015-2018). She led the Fondecyt Regular 1151112 research project "Cultural consecration, woman and spectacle in Latin America: Carmen Miranda, Yma Súmac and Eva Perón" and is currently developing the Fondart Nacional 549522 project "Editoriality in Chilean academic journals of visual arts". Since 2021, she has been part of the Editorial Board of the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR).

Janet Toro Benavides (Chile, 1963). Visual and performance artist, see https://janet-toro.com/

Artist with studies in Fine Art at the University of Chile and in Relaxation Pedagogy. She was a member of the Agrupación de Plásticos Jóvenes (APJ) during the dictatorship, as well as the Plástica Social artist group in 1990. After living fifteen years in Germany, she resides in Chile since 2014. Her visual work delves into social, existential, and political themes, drawing upon intuition, extensive research, and personal experience, with an emphasis on resilience. Through controversial actions and installations, she aims to evoke visual and bodily reflections in the audience, creating a space for resistance, poetry, and questioning. She is featured in the exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, curated by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta, and showcased at the Hammer Museum in California, the Brooklyn Museum in New York, and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo (2017-2019). She has taught performance at the Theatre Faculty of the University of Chile. Her recent activities include Femenino(s). visualidades, acciones y afectuosidad at the Mercosur Biennial (2020), the collaborative performance Ausencia / Presencia in the group exhibition Rebeldes - Laboratorio experimental de prácticas feministas at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile (2022), and La memoria en el cuerpo at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Chile (2023). She is currently exhibiting El cuerpo de la memoria at the Peltz Gallery of Birkbeck University and recently gave a lecture at the Centre for Contemporary Art at Goldsmiths University in Britain (2023).

Voluspa Jarpa Saldías (Chile, 1971). Painter and visual artist, see https://www.voluspajarpa.com/

She holds a Bachelor's degree in Art from the University of Chile and a Master's in Art from the Catholic University of Chile, where she also teaches. Her work involves extensive research and creation around the nature of archives, memory, and the cultural and symbolic notion of social trauma, focusing on the Cold War in Latin America, particularly on the declassification process of U.S. intelligence files in recent decades. Her recent concerns delve into the implications of secrecy as a political modus operandi, its effects on the psyche, and exploring ways to emancipate from these structures. Notable solo exhibitions include En nuestra pequeña región de por acá at MALBA in Buenos Aires (2016), and L’effet Charcot at La Maison de l’Amerique Latine in Paris (2010). Her participation in international exhibitions includes False Flag (2022) at the BAM Biennial of the Mediterranean Archipelago, curated by Beatrice Merz; Altered Views, curated by Agustín Pérez Rubio at the Chilean Pavilion in the 58th Venice Biennale (2019); Proregress at the 12th Shanghai Biennial (2018); Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (2017-2018); and the 31st São Paulo Biennial, Brazil (2014). In 2012, she received the Illy Prize at ARCOmadrid for the work Minimal Secret, and recently she received the Julius Baer Award for Latin American Artists for the work Sindemia, exhibited in Bogotá (2021), Santiago de Chile, and Buenos Aires (2023).

- 1For this reason, the current government of President Gabriel Boric commissioned the formation of an Advisory Committee against Disinformation, an initiative strongly resisted by the opposition on the grounds that it would restrict "freedom of expression", but which has already issued its first report (Anguita, Bachmann, Brossi et al., 2023).

- 2As you can see in this photo by Marco Ugarte from 1983: http://www.archivomuseodelamemoria.cl/index.php/158420;isad

- 3The cueca is a traditional Chilean dance that was reappropriated by the Association of Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared to create "La cueca sola", whose first presentation took place on March 8, 1978.

- 4U.S. intervention includes attempting to prevent the inauguration of Salvador Allende, destabilizing his government through propaganda, communicating with seditious people before and after the coup, providing economic assistance for the deployment of neoliberalism, helping to coordinate South American military regimes (Plan Condor), and overlooking systematic human rights violations.

- 5Popular Unity is the coalition of parties that formed the government of Salvador Allende. This government, which achieved great international renown for defending the democratic road to socialism, was permanently sabotaged before being interrupted by the coup d'état of September 11, 1973.

- 6The Commission was established in 1990 by Patricio Aylwin, the first democratically elected president in 17 years, and is known as the Rettig Commission, after the name of the lawyer who chaired it, Raúl Rettig.

- 7Established by President Ricardo Lagos in 2003 and presided over by Monsignor Sergio Valech.

- 8In addition, there are some 200,000 exiles, some 40,000 exonerated and an undetermined number of detainees by the military regime.

- 9Among them, a representative of Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez.

- 10Almost no military personnel collaborate with the democratic and legal establishment of this political, social and bodily truth silenced by the dictatorial regime.