I dedicate this text to the memory of my dear father, Luis Benavente Arnouil, as a

way of continuing our unfinished conversation about this congress

Introduction

The II Latin American Congress of Artistic Practice as Research took place from October 2 to 4, 2024 at the Extension Center of the East Campus of the Catholic University of Chile (UC). It was an unprecedented event due to its scope, since the seventy participants of its first version in 2022 now increased to ninety, two-thirds of them women, mostly from Chile (65), but also from Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and, to a lesser extent, Colombia, Peru and Uruguay, with some binationals for study or work reasons. In addition, the individual and group presentations made, which included performative conferences, account for the experimental diversification of artistic research. A meeting of this type is conducive to forming an updated idea of research in a given area, which is why I attended the Congress as an observer during its three days. Taking into account that artistic research emerged in the continent towards the beginning of the 2010s, from a tradition of writing about the arts, this Congress indicates that it has been consolidated in little more than a decade, which is surprising. However, with the exception of perhaps the case of Brazil, the mainly European origin of its referents raises the interest of knowing the following: what could be some of the distinctive characteristics of Latin American artistic research?

The question I ask myself does not derive from a desire for identity per se, but from a concern for our futures. In Europe, the emergence of artistic research accelerated, especially in the face of the homologation of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees brought about by the Bologna process from the 1990s onwards. In Latin America, the genealogies to be made should bring us more than one surprise, but our extractivist models have not favored research, a fact illustrated and at the same time aggravated by both dictatorships and neoliberal democracies in recent decades. In Chile, only after the intense student mobilizations of 2011 against profit in education, did research begin to have a real boost: it was adopted as a requirement for university accreditation and in 2018 the Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation was founded. While research in general is associated with the search for development in accordance with new technological and ecological challenges, research in the arts and humanities is usually associated with political challenges linked to democratic strengthening and ontological challenges related to the habitability of the planet; all of which occurs in differentiated and unstable ways. While in Mexico President Claudia Sheinbaum would seek to create a Secretariat of Science and Technology, in Argentina it would be a matter of cutting the budget of the area with a sawmill. The threat, in each of our countries, is real. It is also so at the global level, but due to structural asymmetries, it intensifies here. And although it comes from different conservative flanks, in neoliberal democracies the far-right threat is distinguished by waging its 'cultural battle' against the very bases of knowledge and affection.

Because it is emerging as a key area in the latter field, I tried to approach Latin American artistic research in terms of what could be the bases of its own affective knowledge. The area itself involves a complex hybridization that has been sought to capture by raising different models, since these allow schematizing the main elements of a given reality. The cost is to simplify it in aspects that could be decisive, if it changes. Summarizing Robin Nelson (2022), Practice as Research (PaR) is a model of Anglophone and Nordic origin to which I attribute four main elements: practice or praxis as a generator of knowledge; critical reflection on the processes themselves; conceptual and methodological integration situated, articulated and evidenced; and documented communication of processes. The PaR is a model of academic research aimed at artists, which is why Nelson's book even has a guide for doctoral students. However, this author's insistence that they must attend differently to the academy responds to the need to legitimize inside and outside it the radical ethical-onto-epistemological turn that it entails. The objective in my case was the opposite. Seeking to know the political plots that are woven around knowledge about knowledge, I focused on how artistic research presentations accounted for an integration of and into its cultural context. Under this prism, throughout the Congress I looked for significant imputations or deviations from the PaR model.

Since it had parallel tables, I attended about forty presentations divided into three keynote talks and ten tables of twenty-three. I selected them based on the names I knew or wanted to know, the disciplines of visual arts and theatre and the topics of the environment, feminism and technology. My records, abundant, included annotations, photographs and short videos. My cuts, inevitable, also responded to the fact that from each presentation I took elements that were not always substantial in it, but relevant to my approach. Characteristics inherent to the communication of artistic research made the task more complex: in order to join the academy, it requires some verbal explicitation of its processes; to remain artistic, it requires articulating this explicitness to the non-argumentative formats of research, what Michael Schwab calls 'expositionality'. At the Congress, I navigated an expanded expositionality to conversations and interactions in hallways, coffee breaks, eating out, etc. My immersion in the Congress does not ensure a complete or precise knowledge of the event; it only assures that, in my meeting with the meeting, I changed my vision of artistic research. In writing this text, I further schematized the PaR model —according to my interpretation— in four intertwined zones of knowledge, on the basis of which I assimilated the following differences: in the epistemic zone, the vindication of saber/savoir, as opposed to knowledge; in the critical zone, the weight of autoethnographies; in the ontic zone, bodies as neomaterial foundations of knowledge; and in the communicational area, the ethical orientation to a transacademic relationality.

Know

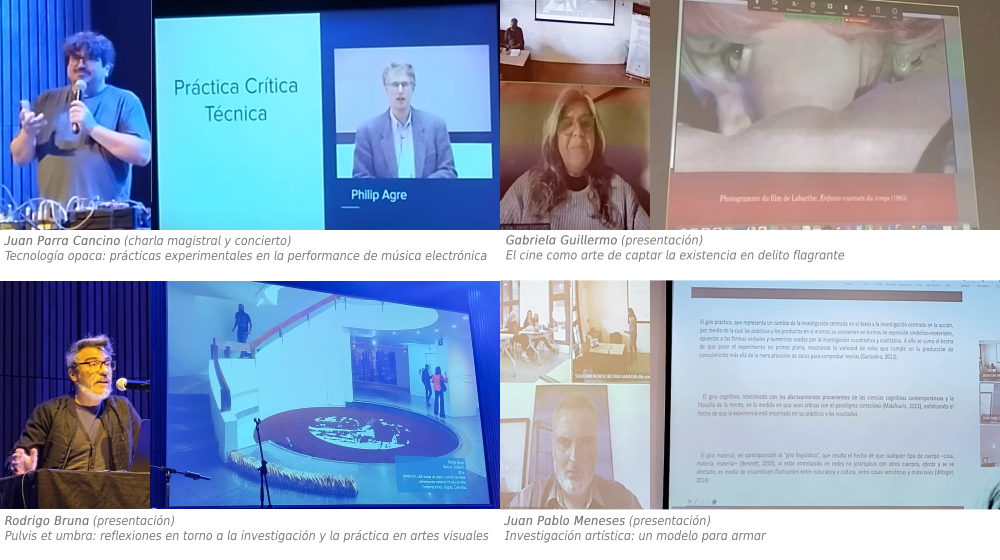

Although it was held under the aegis of PaR, the Congress called for proposals for artistic research in general. In fact, not all of them made an epistemic reflection explicit. This accounts for an openness to different levels of artistic research that is healthy, taking into account the still incipient development of the area. What Juan Parra Cancino (OI, CL/BE) has put forward illustrates well the unusual nature of the meeting, from the point of view of the arts. Within his presentation on technological opacity in musical creation, Parra pointed to the idea of sharing artistic research processes to generate new knowledge potentials. To this end, he referred to the "technical critical practice" of Philip Agre, pointing out that unveiling the "black boxes" of creative processes is part of the "epistemic responsibility" of carrying them out in a research context. Due to the very openness of the meeting, this research context based on PaR faced some explicit and, perhaps, tacit questions. Is the context of artistic research the academy? If this is defined as the space where knowledge is generated and shared, it is, especially if common protocols and standards are adopted to regulate such processes. However, academia is also an institution that has taken on a particular profile in our days; not only or simply because it is hegemonized by science, but also because it privileges the production of knowledge.

In fact, at the Congress it was evident that artistic research does indeed produce knowledge. For example, Juan Parra, articulating a solid theoretical-methodological apparatus and numerous online multimedia archives1, showed the strategies of reappropriation, reconstruction and musical reinterpretation that he uses to explore the constitutive opacity of technologies, contrary to the idea of their supposed 'transparency'. This opacity is manifested through "frictions" of different kinds —for instance, noises— which can be used in turn for musical creation, as he showed in a concert. However, its discovery is part of a process that, in a research context, is shared by resorting to devices that, due to their epistemic nature, differ from those used in musical practice. Moreover, in relation to knowledge, Gabriela Guillermo (ULARE/UP8, UY/FR), when presenting her research-creation on the cinema of André Labarthe, stated that it would allow for a better understanding of it than traditional research. In research-creation, in fact, theory and practice are articulated as "vectors of knowledge" that are not subordinate to each other, but that "share a common epistemology". According to Guillermo, this would allow for "a deeper and more nuanced understanding" of the filmic practice that she herself develops in the film Winter Story, based on experimental procedures observed in Labarthe's poetics of "flagrante delicto".

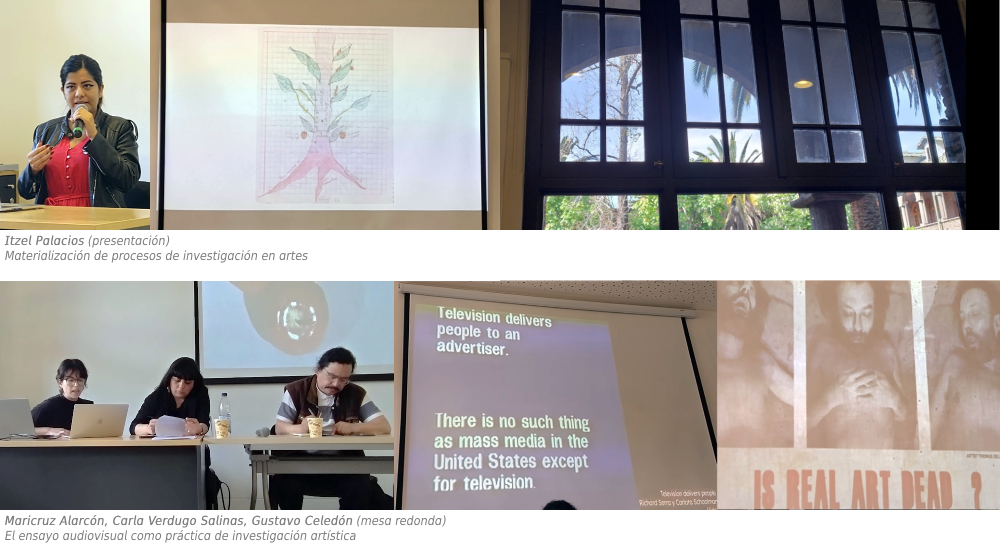

The fact that artistic research generates knowledge from practice raises difficulties to which reference was also made. On the one hand, epistemic difficulties, to which Rodrigo Bruna (UCHILE, CL) alluded when presenting his project "Pulvis et umbra" (dust and shadow), which consists of exploring the social relevance of funerals through installations that have been expanding into multimedia, relational formats and public space. Thus, he noted how, in practice-guided research, the linear model of academic research helps to clarify ideas, but also "contaminates" and "dismembers", often starting the artist at the end. On the other hand, socio-epistemic difficulties were addressed. In his presentation, Juan Pablo Meneses (UASLP, MX) advocated for the validation of the files and devices produced by artistic research beyond the text (logs, diagrams, drawings, etc.), due to the "practical, cognitive and material turn" that it entails. In his discussion with the public, the paradox of universities that refer to complexity, without incorporating it, was confirmed, although it should be noted that they do so only in some aspects. This allows us to understand that Itzel Palacios (UNAM, MX) characterized the academy as a "battlefield", within the exhibition of her eco-epistemosculptural and interdisciplinary process around the "tree of knowledge", as a metaphor that contributes to visualize ideas, socialize practices intermediate to the exhibition and the paper, dimension the continuum between theory and practice and humanize academic work.

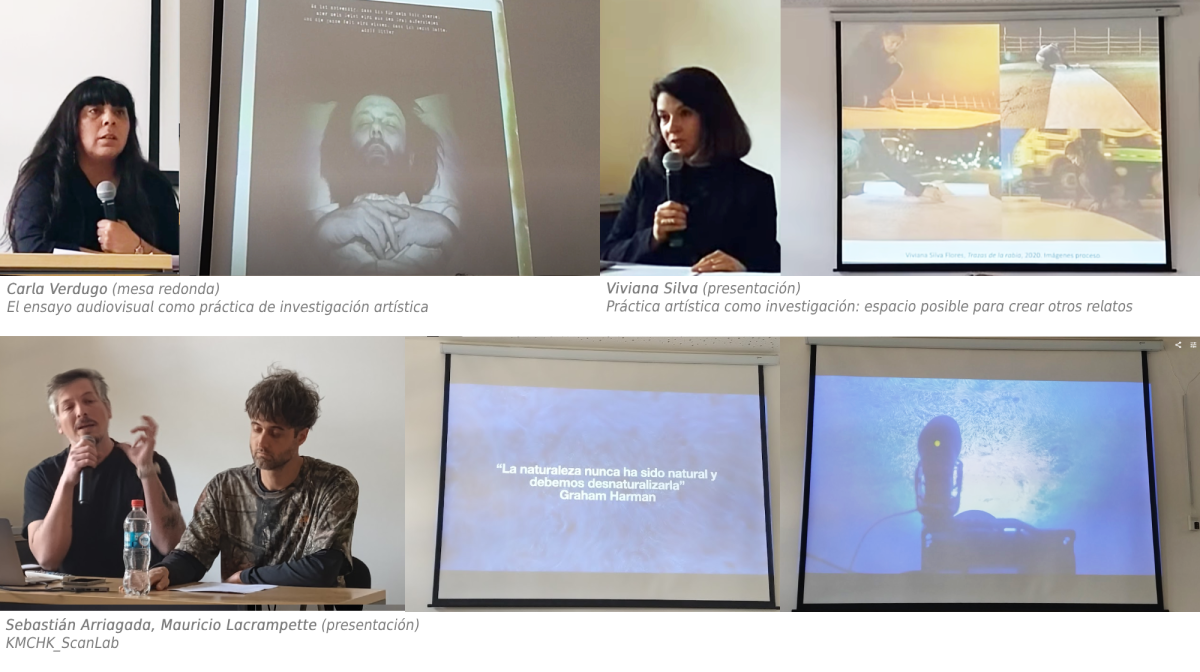

Unlike the previous presentations, the panel on audiovisual essay (UV, CL) directly criticized the idea of knowledge. At this table, Maricruz Alarcón highlighted how, rooted in contemporary art, the film essay "organizes complexities" and raises questions, moving away from mere documentation and aligning itself with artistic research; Carla Verdugo pointed out that it involves montage processes that challenge empirical positivist approaches, by allowing individuals to relate to concrete "things" both in and through images; and Celedón criticized the conception of "artistic practice" as a methodology for producing knowledge, proposing to understand the film essay as part of a broader material montage of diverse saberes/savoirs, in the manner of the Latin American documentary. This critique, in my opinion, is aligned with the notion of "research and creation" with which the place of the arts in the university has been defended in Chile, but showing a turn towards the vindication of its epistemic potential. Recovering the notion of saber/savoir in the perspective of evading the logic of knowledge production seems valuable to me. It cannot be said that artistic proposals in general or the academic ones recently reviewed manage to concretize this evasion, but the notion of saber/savoir offers a guide. Moreover, etymologically, saber/savoir implies the sensoriality of flavour, sabor/saveur, of taste; its kind of understanding implies a sensible experience, a direct contact, a praxis —a word used by Robin Nelson—that brings us back to artistic research to give it a broader, more diffuse and elusive way out of the notion of knowledge. Although the panelists did not address their own creative processes, the first two presentations had a clear expository and visual rehearsal character. This dissociation places them in a diffuse way in artistic research as an area of hybridization that also concerns saber/savoir and knowledge.

Autoethnography

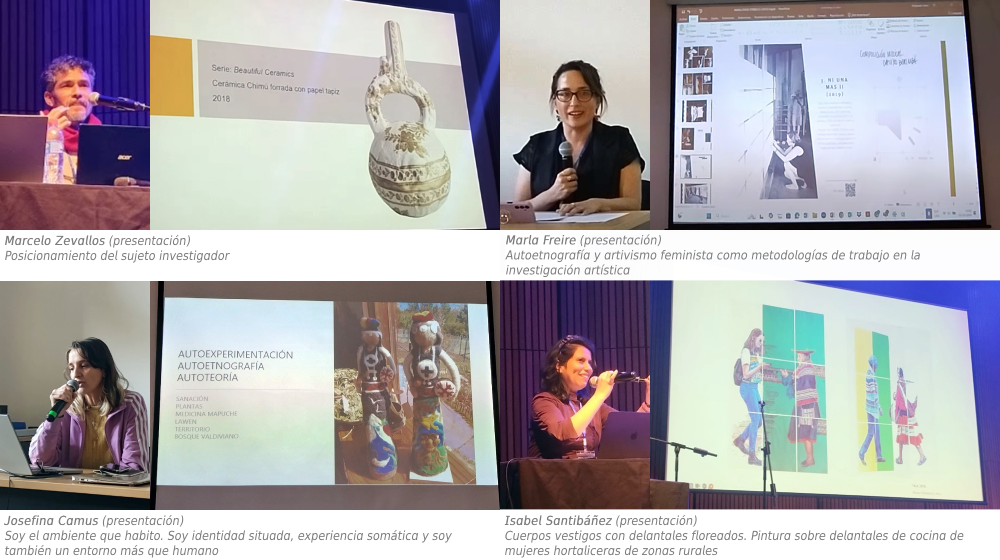

While from the point of view of PaR autoethnography could be considered as one method of knowledge among others, throughout the Congress it was rather outlined as a crucial and distinctive method of self-knowledge. This interdisciplinary tool was the object of explicit and theoretical approaches, but it was also articulated in tacit and performative forms. Marcelo Zevallos (UNLP/ENSAD, AR/PE) reflected on it when addressing the construction of the researcher-creator subject, conceiving it as a methodology that allows exploring the border between personal and cultural experience. Emphasizing that it requires immersing oneself in one's "own wound" and leads to experiencing "lucid suffering," He then presented her own research-creation work around Chimu ceramics, relating it to the experience of racism. Through his presentation, Zevallos, among others, presented at the Congress the model of research-creation, of rather French-speaking origin and which assimilates creation to the arts. Its approximation allowed us to dimension this model in terms of an object/subject axis that, in PaR, is structured around the theory/practice axis.

Marla Freire (UPLA, CL), from research guided by artistic practice, also organized her presentation around the topic of autoethnography, reflexively recounting how she drifted towards it from autobiography while moving from art to theory, activism and artistic research, passing through the social sciences. For Freire, research guided by artistic practice is a feminist strategy for generating knowledge that challenges traditional academic logics. In a similar way to Zevallos, she conceives of autoethnography as an interdisciplinary methodology that allows individual experiences to be connected with social contexts, accounting for the factors that motivated his artivisms against femicides "Ni una Más" (2007) and "Ni una Más II" (2019). Josefina Camus (GOLD, CL/GB), for her part, placed her within a broader set of processes of "self-experimentation, autoethnography and self-theory" that, from feminism, have been fundamental in her practice of artistic research. The artist presented different experimental investigations that she carried out around the connections of body, territory and spirituality through ice sculptures, multisensory spaces and, in the manner of Lygia Clark, therapeutic relational objects. She then referred to his incorporation of non-Western epistemologies and how she came to know in the field, with a machi, the Mapuche concept of "itrofil mogen" or multiversity.

Just as Zevallos and Freire's critical reflections on autoethnography allow us to think of it as a border between the individual and the cultural, Camus's conception contributes substantially to revealing the existence, in artistic research, of a dimension that we could call "autology". This constitutes a crucial departure from PaR, as this model underlines the need to articulate a critical reflection based on a common language and the presentation of evidence, seeking to divest itself of contextualizations and exegesis or personal interpretations. Robin Nelson even warns of a danger in doing so, since in the context of post-truth “individuals assert their viewpoint in defiance of the evidence" (2022, p. 25). For this author, the presence of reflections focused on the self would make it possible to distinguish the model of artistic research —which I take in this paper as a larger area— from the model of PaR. It is not the case to dwell on a point that would take us very far, but the interdisciplinary recourse to autoethnography seems to be precisely a response to this post-truth danger, since it disciplinarily frames reflection on the self or the subject. By the way, I propose to speak of "autology" in order to transcend the ethnographic framework, since we could and perhaps should speak of an autosociography and, even further, of an autoscientography, which would help to situate any research practice in a framework of responsibility and personal ethical commitment. Despite this, autoethnography has a reason to exist, since, especially in Latin America, it places us on the borders of the West.

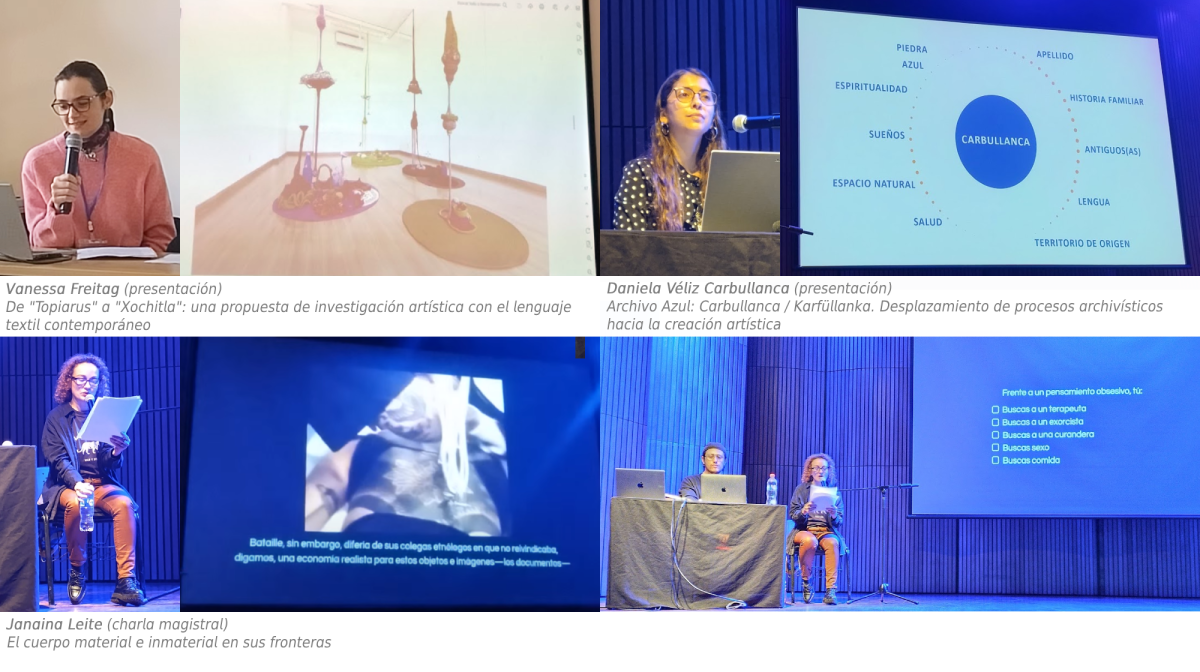

In fact, although it was not always explicit or theoretically elaborated, autoethnography could also be recognized in the references to a past where the family also functions as a border between the individual and the cultural. In Isabel Santibáñez (UC/UACH, CL), the family appeared in relation to the activity of sewing, when she presented her pictorial research on the clothing of Cuzco and Mapuche women, pointing from Ronald Kay to the stain as a symptom of the disappearance of the indigenous female body. Similarly, Vanessa Freitag (UGTO, BR/MX) referred to her Brazilian grandmother's garden to present her textile exploration of gardens, placing it in a global warming and Mexican industrial urban context to embrace recycling, walking or collaboration, but also the Nahuatl notion of 'xochitla', place of flowers. In the case of Daniela Véliz Carbullanca (UDP/UC, CL), the artist presented her "Blue Archive" as part of an exploration of the Mapuche surname inherited from her mother, 'Kallfüllanka', a blue gemstone, highlighting that the archive is not only about past reality, but also allows for the creation of fiction and the future. And Janaina Leite (USP, BR), in her keynote lecture on her research on the body dissociation between the physical body and the virtual body, referred to her own personal experience of progressive deafness, with allusions to her family and friendship ties. In addition, within his careful exhibition proposal, he referred to and exhibited Georges Bataille as the main visual and theoretical reference. Thus, even more than personal or individual self-knowledge, autoethnography is the vector of collective, social and cultural self-recognition. A diversity of invisible or plundered knowledge emerged among the writings and the languages used, which could lead to a term, an image, a sound, a gesture or its interaction, another vision of the world, another cosmovision.

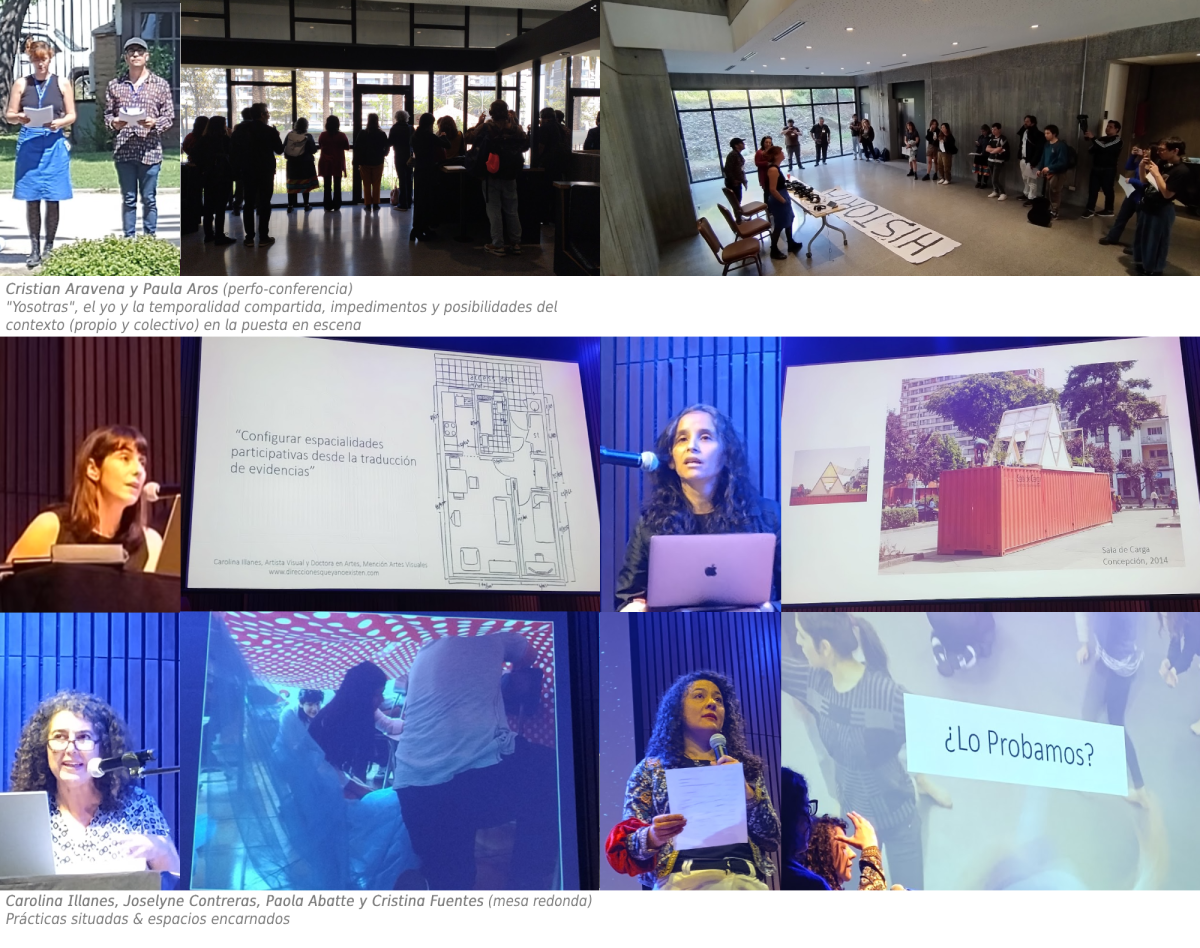

Due to the above, autoethnography can also be associated with the spatiotemporal redimensioning of research and creation practices. By awakening to self-consciousness, objectified subjects activate intersecting futures. The participatory theatrical conference "Yosotras", by Cristián Aravena and Paula Aros (UMAYOR, CL), performed History as an undulating transindividual "network". The experience, which took us out of the auditorium, included actions behind a window, an mp3 that we listened to with headphones and a final conversation around a canvas with the word "HISTORY", along with the delivery of sheets with arrows as vectors of others/our stories. The round table on spatiality by Carolina Illanes, Joselyne Contreras, Paola Abatte and Cristina Fuentes (NIA UC, CL) complemented the previous one. Illanes presented her research on the changes in her house, her neighborhood and her city using legal documents, plans and visual records to explore the right to inhabit through different devices. Contreras approached the curatorship of exhibitions as an activation of "other" relational spaces in the urban environment. Fuentes presented the sensory immersive theater through which she invited during the pandemic to build "houses of emotions" as heterotopic spaces. And, finally, from stage mindfulness, Paola Abatte proposed exercises to become aware of body spatiality, such as feeling the feet root and the heart beating. Whereas decades ago, after quarrelling with history, certain perspectives took refuge in a nomadic space, today it is more a matter of recovering concrete, situated and rooted places of life, without losing a sense of mobility. Moreover, unlike the neoliberal exitist and egoistic self, the ego of affective saber/savoirspeaks, writes, does, and acts not only or simply for itself, but also with others, from a transindividual consciousness.

Corporeality

The above is related to a major epistemic change: the ontological turn towards new materialisms, which attribute agency, relationality, and dynamism to matter. In fact, following Rodrigo Menchón, the realist Quentin Meillassoux criticizes them for escaping anthropocentrism by assuming an anthropomorphism according to which "we must accept that the categories we use to describe ourselves are valid for all of reality" (Menchón, 2021, p. 68). At the Congress, the new materialisms were present above all through references to concepts of feminist and ecofeminist philosophy such as Karen Barad's "ontoepistemology", Jane Bennett's "vital materialism", Barbara Bolt's "material thought" and even, in an intermediate place, Donna Haraway's "agential realism" and "sympoiesis" or co-construction between agents who can be human or non-human. Other thinkers referred to at the Congress cannot be characterized as materialists, but they communicate with this thinking in some ideas, such as Graham Harman and "Object-Oriented Ontology OOO", which highlights the autonomy and depth of objects beyond their relations —he is the main object of Meillassoux's critique of anthropomorphism—, and also Bruno Latour, with his Actor-Network Theory, which highlights the agency of the non-human and the dynamic relationships between actors, especially in the field of knowledge. Thus, Rodrigo Menchón continues, for Karen Barad, "if all entities are vital, active and creative, have feelings and exercise agency, the distinction between the animate and the inanimate also ends" (p. 69).

References to the new materialisms were carried out at the Congress in different and intricate ways. In some cases, it concerned non-human and non-organic entities as active participants in artistic creation, with Barbara Bolt's theory of material thought and Andrea Soto Calderón's performativity of images as common references. Thus, Carla Verdugo (UV, CL) invited us to "not only think about images, but also think about the thinking of images", proposing the film essay as a means of relating individuals with, among other diverse "things", "things-images, and things-catastrophe and things-images-of-catastrophe". Likewise, Viviana Silva (UCS, CL) and Rodrigo Bruna (UC, CL) agreed to claim representation, but now reconsidered based on its capacity to have a specific impact. By exposing her research on memory through performance and disruptive installations, Silva articulated this idea through terms such as re-repeat, re-remember and re-portray, while Bruna exposed how funerary images and materials allow the past to be resignified.

Another type of search, but with some references common to those of the previous presentations, is the collaboration between the artist Mauricio Lacrampette and Sebastián Arriagada (UC, CL), who presented the "Laboratorio de exploración de la niebla camanchaca" or "KMNCHK ScanLab". Based on Andrea Soto Calderón's discussion of the performativity of the image, crossed in this case with Jean-Louis Déotte, this presentation revolved around a technological device created to scan the camanchaca, the thick fog that forms in the Chilean desert. The device consists of a fog catcher equipped with light sensors that "seeks to produce a new encounter between human and non-human agents of the landscape, opening a new threshold of understanding towards this climatic entity through an aesthetic operation on a human scale carried out in the form of a terrestrial expedition" —drifts, détours—. Also referring to Graham Harman, Manuel de Landa, Bruno Latour and Karen Barad, among others, the panelists explained how the camera, as a performative vector and sensory prosthesis, interferes with the materiality of what it records and with which the artists interact, highlighting that "the imaginative power emerges from the bowels of the device".

In the PaR model, Robin Nelson gives Karen Barad's onto-epistemology an important place, since it allows the articulation of being and knowing. However, the anthropomorphism that Meillassoux attributes to the new materialisms leads me to highlight corporeality as a key ontic foundation of this new materialist and feminist knowledge. At the Congress, numerous exhibitions revolved around the human body. In the case of Isabel Santibáñez, as we have seen, it was the body represented by indigenous women in their disappearance. In Viviana Silva's case, it was about the performative body, used in disruptive practices that seek to show relationships that would otherwise be invisible, as she pointed out, referring to the moderator of her table, Natalia Calderón (SPIA UV, MX). In Paola Abatte's work, the sensory body, conceptualized from Spinoza and Gilles Deleuze, was the object of a work of emotional emancipation consisting of creating, in pandemic domesticity and involving especially women, simple scenography of small houses. In Janaina Leite's study, the relationships between the material and immaterial bodies were investigated based on the symptoms of her progressive deafness, with medical, psychedelic, technological and auto/ethnographic experiments. Her announced research on theater and pornography, developed on networks in the pandemic as an experience of "othering" and dispossession, was preceded and gave rise to others, such as the development of pseudoscientific questionnaires, the creation of a 3D virtual space and the projected design of a video game. Through them, Leite pursues the sacred dimension of a body that, confronted with danger or bordering on death, vibrates somatically with the world in the frequency of life.

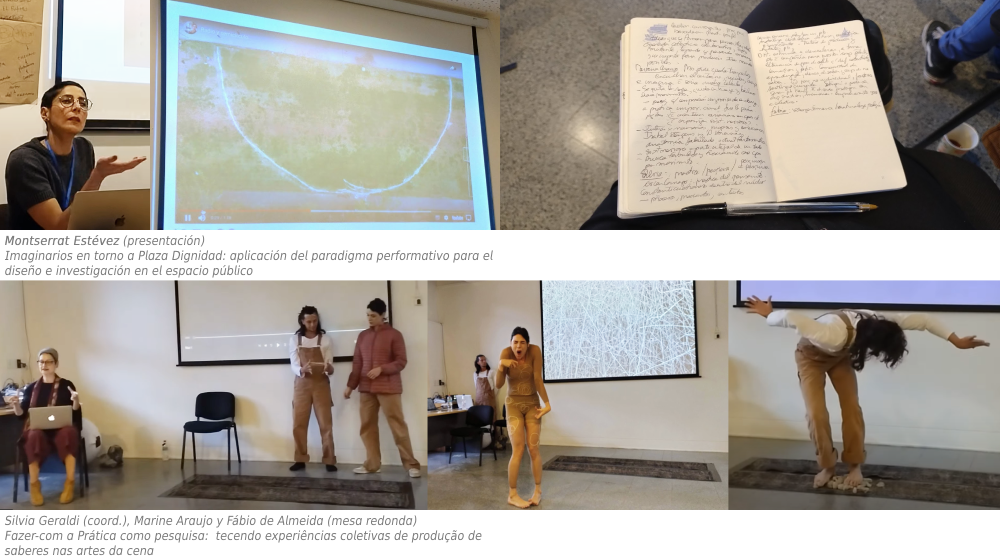

I focus the somatic body through its epistemic articulation to artistic research. It is the self-perceived physical body, but now, following the references to Karen Barad, in an "intraction", that is, co-constituted with the environment. For Josefina Camus, water connects the body as a micro-world with the environment as a macro-world, a perspective of the hydrofeminist Astrida Neimanis that she investigated through ice sculptures, and then opened up to other somatic experiments. In the case of Montserrat Estévez (UC), based on Barbara Bolt, the artist held a meta-discussion on PaR from Brad Haseman's post-qualitative performative paradigm and Karen Barad's onto-epistemological paradigm. Through records of measurement and transposition actions of Plaza Dignidad —the epicenter of the social outburst of 2019— she presented her "performative program" around the "performative data", stressing that this is not immutable, but is born in interaction, and concluding that "I contain the plaza within me". Silvia Geraldi, Mariane Araujo and Fábio de Almeida (UNICAMP, BR), for their part, staged their collaborative and sympoietic perspective by asking us to make a ring, playing string in the back room and giving dance-video conferences around neurons (Araújo) and theater-installation around the landscape and an owl (Almeida). Proposing from Óscar Cornago and Donna Haraway that artistic research is also an "inquiry about research", Geraldi stressed that her group works around the somatic body, while Araujo and Almeida stressed that the forms generated in their performative investigations are intertwined.

Relationality

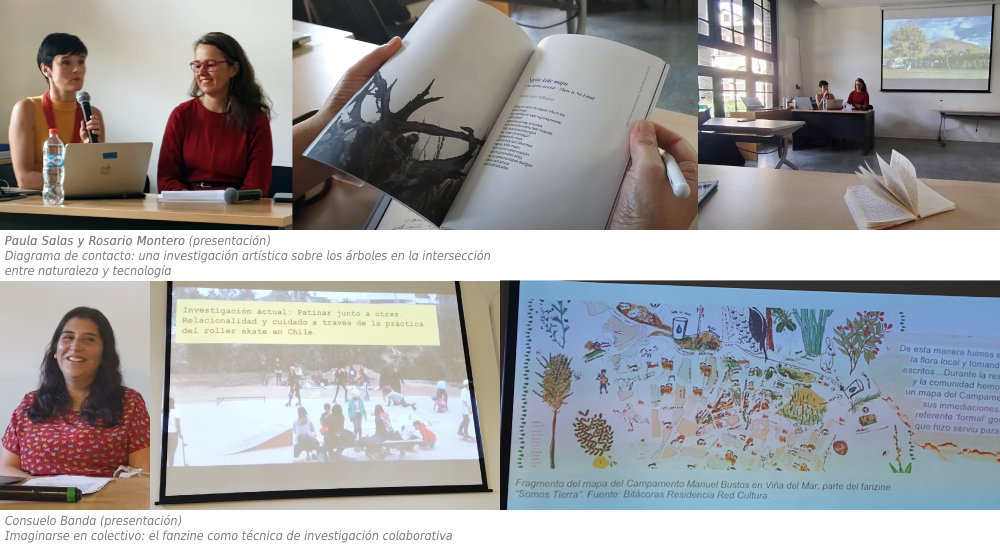

The Congress included a variety of transepistemic relational initiatives, understanding transepistemic as the incorporation of knowledge that overflows and transforms the field of specialized epistemic production. This also constitutes a significant departure from PaR, showing that artistic research communications not only need to address a closed academic community, but can also integrate other actors. In turn, these initiatives are associated with concrete experiences from which we do not simply seek to change things, but rather the way of understanding them. For this reason, the academy becomes a focal and nodal site of agency for the establishment of other relations of knowledge-power. From there, epistemic intraction can arise with any entity: water, lichens, cities, camanchaca, dignity, cells, stones, images or, in Fábio de Almeida, the owl that symbolizes knowledge itself, knowledge of knowledge. Thus, Rosario Montero Prieto and Paula Salas (UC, CL), academics and members of the Agencia de Borde collective, presented "Contact Diagram", a research that combines forest explorations with their families and other artists with the tactile printing of bark on stoneware ceramics as an intermediate materiality, exploring the affectation between humans and trees through media, musical, written and visual collaborations. In a similar, but also different, way, Consuelo Banda (UCHILE, CL) exposed the "fanzine as a collaborative research technique" around intergenerational care in skating. To this end, she referred to experiences of previous editorial laboratories, the generation of narrative consensus and the management of materials, among other aspects, highlighting the challenges that his project entails as a form of representation and empowerment of the community. And it is this openness to the community and its integration into an affective experience of knowing that makes the difference.

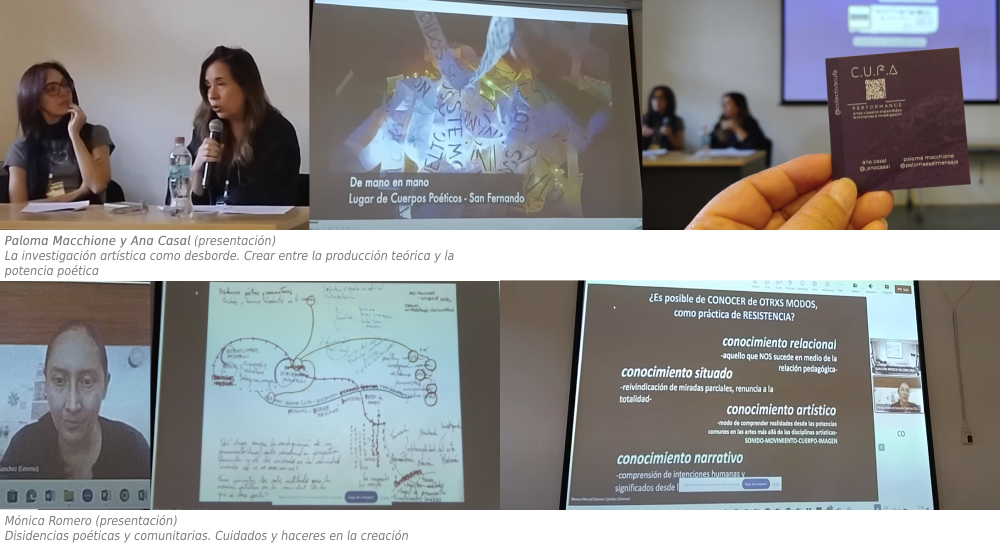

At the feminism table, together with Marla Freire, Mónica Romero (PUJ / UNC, CO) and Paloma Macchione with Ana Casal (UNA, AR) were presented. The latter addressed the "hacking" of patriarchal production that, using transfeminist, post-qualitative and performative methodologies, and from an activist conception of artistic research, they have developed around the relationships between texts, bodies, art and academia with the Unique Collective of Artistic Fabulations (CUFA). Mónica Romero (PUJ / UNC, CO), via Zoom, highlighted the importance of affective communities in the face of capitalist, patriarchal and colonial violence. She defined artistic, relational, situated, and narrative knowledge as practices of resistance, and linked artistic research and teaching to transgress the canon from the edges of academia, creating devices and practices aimed at "emotionalizing" public life with/from the body. The almost zero attendance at this table was surprising, especially considering that two-thirds of the panelists at the Congress were women. This may be due to the exhaustion of the feminist wave, but, considering the transversal references to Donna Haraway, Jane Bennett, Karen Barad, Sandra Harding or Astrid Neimanis, among others, there is no doubt that critical feminisms, more than a topic, are an agency force.

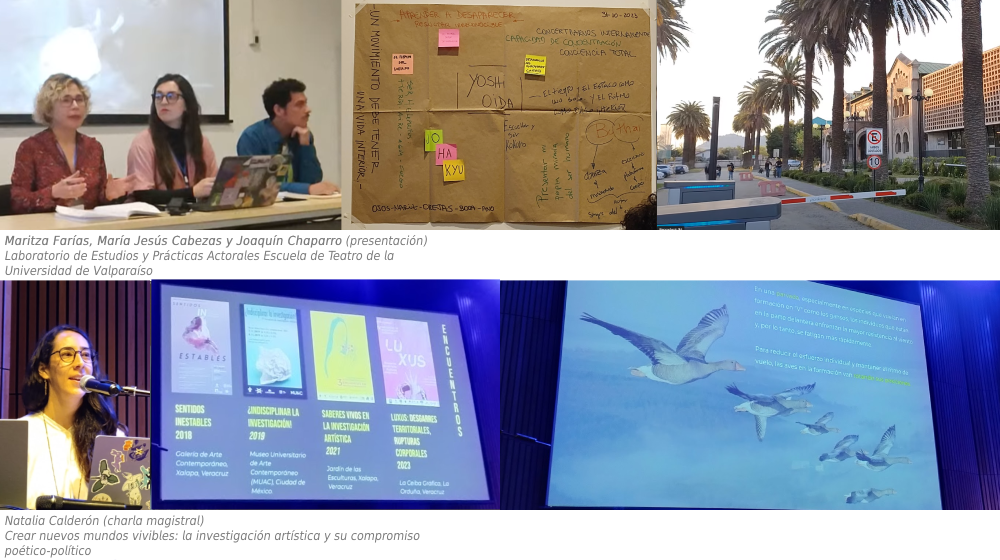

At the edges of academia, some artistic research initiatives have greater institutional support. When presenting the Laboratory of Theater Studies and Practices (LEPA UV, CL), her coordinator, Maritza Farías, explained that she founded it in 2023, after learning about Armando Sergio da Silva's work at CEPECA (USP, BR) in 2011. The LEPA UV, which depends on the School of Theater and receives support from the Centro de Investigaciones Artísticas (CIA UV, Center for Artistic Research UV), seeks to "contemporanize" the training of "researchactors" and provide continuity of studies to graduates of the School of Theater such as panelists María Jesús Cabezas and Joaquín Chaparro. The Núcleo de Investigaciones Artísticas NIA (Artistic Research Nucleus) was presented by Soledad Pinto (UMCE/UC, CL) at the table on spatiality as an interdisciplinary entity that was born from the UC Doctorate in Arts, but later integrating other researchers. In her keynote speech, Natalia Calderón (UV, MX) presented the Permanent Seminar on Artistic Research of the Universidad Veracruzana (SPIA UV), one of the most active instances of artistic research in Latin America. She emphasized the need to articulate the poetic, the political and the imagination to propose alternative and committed forms of organization and coexistence in the generation of knowledge. By presenting encounters, actions, publications, podcasts, and other productions, she exposed artistic research as an inter- and non-disciplinary process that links art, nature, and technology to explore multispecies and non-human relationships in the creation of livable worlds. The SPIA seeks to generate new sensitivities in everyday life, integrating fictions and collaborations beyond traditional academic frameworks and in a way that is situated in the mesophilic forest of Xalapa.

Conclusion

To conclude this itinerary, I will first recall its main results. When I took the PaR model as a guide, I accommodated myself to its elements and to what in an exercise of abstraction I called its central zones. Based on what each of the different presentations known at the Congress indicated to me, I proposed in a certain way to turn it around, to look at it from below, in order to overcome its elitist vocation and reconnect it with a living cultural substrate that can be epistemically enhanced. I announced what I had done in the introduction, but I would like to highlight this inverted view now: in the epistemic zone, I noticed how artistic research does indeed produce knowledge, but also that the incorporation of the notion of saber/savoir would allow its exclusive circulation through academia to be avoided; in the critical zone, I observed the weight that autoethnographies had within what could be called autologies, as a necessary complement to any critical reflexivity and because it allows situational and contextual articulations; In the ontic zone, which is actually ontoepistemic, the new materialisms and anthropomorphism attributed to them led me to highlight bodies as foundations of knowledge, bodies mainly of women researchers in relation to other invisible, marginalized and threatened bodies; In the communicational zone, which I first thought of as an organizational zone, I noticed some outlines of a transacademic relationality that still has a lot of room for expansion, but that already knows relevant activations.

The saber/savoir is there, the bodies that investigate know it and the knowledge helps to perfect it. In Chile, in the feminist mobilizations of 2018 and in the Social Outbreak of 2019, looks, demands, slogans closely related to the positions known in Congress were manifested. Precisely from the universities, they had managed to permeate the social body, strengthening themselves during the mobilizations. But the reaction was not long in coming and, in the face of this, artistic research can give at least two answers: one of them, perfecting its interventions from a more complete knowledge of its problems and contexts, as well as its own places of enunciation and techniques, to generate new artivisms; the other, generating spaces of affective knowledge adapted to a more general public, according to transindividual modes of artistic-epistemic co-construction. Surely, the latter happened in the backroom of the mobilizations and also through the aborted constituent process, but it is possible to continue expanding these spaces. Perhaps, together with cultural institutions, universities or academia in general can continue to be the institutions that host them, this time officially, through the PaR and initiatives similar to those of Yosotras or the NIA, for example.

List of acronyms

ENSAD, PE: Escuela Nacional Superior de Arte Dramático, Perú

GOLD, GB: Goldsmith College, Gran Bretaña

IO, BE: Instituto Orpheus, Bélgica

PUJ, CO: Pontificia Universidad Javierana

UACH: Universidad Austral de Chile

UASPL, MX: Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, México

UC, CL: Universidad Católica de Chile

UCSH, CL: Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez, Chile

UDP, CL: Universidad Diego Portales, Chile

UDELAR, UY: Universidad de la República, Uruguay

UGTO, MX: Universidad de Guanajuato, México

UMAYOR, CL: Universidad Mayor, Chile

UMCE, CL: Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación

UNICAMP, BR: Universidad de Campinas, Brasil

UNAM, MX: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

UNLP, AR: Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina

UNA, AR: Universidad Nacional de las Artes

UNC, CO: Universidad Nacional de Colombia

UP8, FR: Universidad París 8, Francia

UPLA, CL: Universidad de Playa Ancha, Chile

USP, BR: Universidad de Sao Paulo, Brasil

UV, CL: Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile

UV, MX: Universidad Veracruzana, México

UCHILE, CL: Universidad de Chile

Notes

1. In the Research Catalogue, the platform that supports the publication of JAR and was created for this purpose.

2. The criticism is from the philosopher Quentin Meillassoux, but referring to him would take us to another place.

References

Nelson, R. (2022). Practice as research in the arts (and beyond): Principles, processes, contexts, achievements (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan

Menchón, R. (2021). "The Return of the Repressed of Metaphysics". In Harman, G., Meillassoux, Q., Brassier, R., & Hamilton Grant, I. (2021). Speculative Realism: A One-Day Workshop (R. Menchón, Ed.). Arena Libros.

Biography

Carolina Benavente Morales (Chile, 1971). Experimental researcher in art, literature, and culture.

She holds a Ph.D. in American Studies with a specialization in Thought and Culture from the University of Santiago de Chile, and a Bachelor's degree in History and Political Science from the Catholic University of Chile. She grew up in France and Mexico. She co-organized, alongside Ana Pizarro, África/América: literatura y colonialidad (FCE, 2014), edited Coordenadas de la investigación artística: sistema, institución, laboratorio, territorio (Cenaltes, 2020), and authored Escena Menor. Prácticas artístico-culturales en Chile, 1990-2015 (Cuarto Propio, 2018). She co-founded and directed Panambí. Revista de investigaciones artísticas and the Centro de Investigaciones Artísticas (CIA-UV) at the University of Valparaíso (2015-2018). She led the Fondecyt Regular 1151112 research project "Cultural consecration, toman and spectacle in Latin America: Carmen Miranda, Yma Súmac and Eva Perón" and is currently Journal for Artistic Research developing the Fondart Nacional 549522 project "Editoriality in Chilean academic journals of visual arts". Since 2021, she has been part of the Editorial Board of the (JAR).

- 1In the Research Catalogue, a platform that supports the publication of JAR and was created for this purpose.