Felix:

I think that we are approaching a consensus, particularly in the arts and humanities, that the contemporary condition requires new epistemologies, new ways of knowing, or, perhaps more importantly, new ways of learning. This has to do with the fact that the present is characterized by a multiplicity of agencies in complex, dynamic, often opaque settings. While critique remains important, of course, many of the modern methods for producing critique — distance, separation, disinterestedness, and universality — are perhaps no longer productive, even without considering the problematic historical legacies of these methods, imbricated as they are in coloniality and the destruction of nature.

Rather than being confronted with stable objects that we can point to, we find ourselves immersed in situations that require research to untangle, intervene and transform. In other words, rather than being disinterested observers, we — as researchers, curators or artists — are constitutive agents in an open field with many other constitutive agents, human and non-human, entering into, and disentangling from, cooperative as well as adversarial relations. However, when it comes to aesthetic practices of exhibiting, conventional, modern formats are still prevalent. Against this background, I would like to talk to you about your recent curatorial practices, which you see as a research process, a framework of open-ended and ongoing exploration and learning, rather than as something where the results of research are made available to the public.

in January 2019© Aya Schamoni

Olga:

Let’s take the project New Alphabet School that we organized at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin from 2019 to 2022. The basic idea behind it was that different ways of knowing in- and outside academia and the arts can be brought into relation by focusing on the practices of knowledge production. That’s why we organized gatherings dedicated to practices of Learning and Unlearning, Translating, Situating, Instituting, Feralizing, Commoning etc. The idea was that common methodological questions could be addressed between artistic, academic, activist and community practices. Questions of how to frame a topic, from which perspective to tell a story, how to work collectively, how to address untranslatabilities and opacities, were equally shared by academics or researchers in the context of art and culture, people working in the context of NGOS or activist projects. So, the New Alphabet School enabled exchange between researchers, or knowledge workers if you will, in very different fields, asking how knowledge can be both situated and relevant on a planetary scale. It became a way of doing research from the curatorial perspective, because each edition was developed in conversation with school members who came forward to propose a place from where a specific practice should be addressed. For instance, members proposed to work around the question of Instituting from Athens, where a lot of the public and cultural sector had been destroyed after the financial crisis and people at the time had learned to self-organize and squat theaters and hotels to institute alternative spaces. And then other members proposed to work with APROSMIG, a self-organized alliance of sex workers from Minas Gerais in Brazil, who are working towards creating a museum of sex work in order to institute recognition and knowledge around their work. So, they were invited to join this session in Athens. The practice of curatorial conversations was one of weaving an argument and a constellation which can be seen as open-ended research.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

Our recent curatorial project is an investigation into ‘Unreal Data’. Unreal Data explores the inherent ambiguity of data as an opportunity not just to describe the world, but to strategically intervene into it. Is it possible to create specific real-world outcomes by modifying our data streams? Within our research we are interested in how the unreal quality of data is identified and strategically used to game the system in different areas of life and different technological systems. Our investigation found unreal data practices in activist projects, in collective actions, but also described in theoretical texts, by sociologists and by journalists. So, curating allowed us to bring together works, practices and investigations of unreal data in a way that we would have struggled to achieve, say, in an academic text or a single artwork. Curating allowed us to show artworks within an exhibition space, and include performances, talks, podcasts, publications. We see the curatorial work within Unreal Data not as an output format to show the results of a research project, but as an extended, open-ended conversation that we as researchers have with other artists, researchers and publics.

Our curatorial practice is closely linked to and intertwined with our artistic practice. As artists, we explore networked technologies and their implications for our societies, how they change and shape not only communication but all aspects of our lives. We do this using both the classical methods of research, but also through hands-on experimentation. Attempting to find the breaking point in technological systems, we misuse technological tools to explore the – intended and unintended – uses that may also be inscribed in a technology. Take a technology like surveillance cameras systems for example: Can we tap into them? And when we do this, how does having access to the images change our relationship to the city? In which way can the space before a camera become a performance space? A space for critique?

When so many of our daily interactions are mediated through technology, it seems urgent to also expand the fields of art, of artistic research, of curating and develop the formats and tools to reflect on these developments. The shiny and seamless surfaces that our new technologies present require critical examining, artistic imagination, questioning and deconstruction, all practices that art is good at and curating can expand on.

Felix:

Research, like making art, has traditionally been conceived as a relatively linear process in which the first part, the actual research or the making of the artwork, happens largely in secluded spaces, withheld from the public, like the studio or the laboratory. Once this work is done, the results are presented to the public in relatively standardized formats, say the research paper or the (white cube) exhibition. The open-ended processes that you have developed on the contrary consist of a multiplicity of formats, which seem to correspond with different ways of doing research, of curating, and of working together.

Olga:

Curatorial research is a very embodied, experience-based and conversational one and it is based on a shared curiosity and trust. The level of objective distance is hence extremely low. Sometimes workshops in the New Alphabet Schoolstarted to feel like therapy sessions where members for instance exchanged experiences of racism or othering. Such research can only take place collectively and when everybody is open to sharing. It cannot be done by one analyst/interpreter/researcher who collects other people’s experiences. A lot of what could be considered outcomes of this research can also not be published as an outcome but stays within the semi-public processes of conversation and collective organizing. Often what participants learn is how to address asymmetrical power relations in which they themselves play a role. In that sense it is a lot about raising awareness of vulnerabilities, of privileges etc. Formats emerge out of the curatorial process and cannot be determined upfront.

at Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin in September 2022© Laura Fiorio

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

Also in the case of the Unreal Data research, the research is embodied and knowledge and knowing is often anecdotal and based on experience. Many of the artistic practices we show are based on trial and error, engaging with systems and attempting to decipher patterns in order to draw conclusions. Artists who work with technology increasingly handle, disrupt, intervene into technologies that are becoming more and more opaque. They also develop with mind-boggling speed. This requires artists to find other ways of engaging with the technological contemporary that are immediate and embodied. In the role of curators, it is then interesting for us to bring different and often disparate artistic practices into one exhibition space. Both as a form of thinking together and as an attempt to form a relationship between research, formats and practices that may as yet be unrelated to each other.

AIA Zurich, 2022. Photo: Martina Huber Marthaler / AIA

Felix:

Olga, you also point out that you do not want to speak about artistic initiatives, but that you aim for a mode of ‘speaking nearby’ or ‘together with’, terms you borrow from the post-colonial theorist, composer and filmmaker Trinh Minh Ha. And Carmen, I assume this also resonates with your work?

Olga:

As a curator I think there is a certain common understanding to act as a host for the artists you invite and through that to be in conversation with them. So, speaking ‘with’ someone instead of speaking ‘about’ them is kind of self-evident. As an academic researcher you are usually expected to keep a critical distance, which is not really possible in curating. Trinh T. Minh Ha uses this expression of ‘speaking nearby’ to emphasize that the antidote to objectification and Othering, especially in anthropological research, is not just a mode of participant observation, but about joining in a struggle and a cause and being in solidarity with those one is doing research ‘with’ rather than ‘about’. Hence you don’t study the practices of artists or activists or whoever it is you are hosting, but you study with them. A curator then is someone who invites others to work on a question and to be invited back by them to follow their practices and their lines of thought, which might even change the question one asked in the beginning.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

Yes, both the term and Olga’s elaboration of it, how she understands it as a form of solidarity and being with someone, resonate. When we work with artists on an exhibition, we do so as artist-curators, as peers. We study with them; we exchange ideas and we try to be accomplices to their work. Speaking near resonates especially also when talking about artistic practices within the techno-political sphere. Oftentimes those affected most by surveillance, by bias and by the worst aspects of algorithmic governance are marginalized communities, minorities, refugees. As artists we see and make these struggles visible without necessarily being affected ourselves. Of course, it is important to do this in solidarity with the communities who are directly affected.

Felix:

When we speak about opacity as it relates to socio-technical systems and the complexity of cross-cultural, multi-agent processes. We might also be tempted to respond to this with a call for transparency and the kind of rationality this enables. However, in your work, opacity is much more than that, it’s a resource, a condition that opens up possibilities.

Olga:

The way I understand Édouard Glissant’s notion of opacity is that it stresses the unavailability of what can be known, especially in a colonial situation in his native Martinique, where the French enlightenment tradition demanded the transparency of the colonial subject not just to know it, but also in order to govern it. To make something visible in such an asymmetrical situation implies to render it ready at hand for exploitation and appropriation, to allow for it to become part of the inventory of the museum collection of the colonizer so to speak. In such a situation, opacity for Glissant in fact is the basis of relation, because it is “that which cannot be reduced, which is the most perennial guarantee of participation and confluence” (1997: 191). He sees opacity as a reminder “not to think in the world, which could again lead to ideas of conquest and domination, but to think with the world” (2009: 46) and as generating “stubborn shadows where repetition leads to perpetual concealment, which is our form of resistance” (1989:4).

And both curating and artistic practices can be a beautiful way of creating spaces of opacity in that sense, because they invite others into joined processes where things can remain implicit instead of having to be explained or made explicit. Opacity then is not seen as something that has to be made transparent as in the case of technology but it can be something that is invited or even produced in order for certain opaque processes to take form in the first place. Not everything is a discernible object or a hidden function we need to unmask or reveal, but a lot of knowledge lies within how things are done differently. This also changes the mode of criticality, which is rethought as a practice of care. It is a criticality that comes from a position where one is immersed in processes rather than claiming an outside objectivity.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

In the case of technology, opacity is more often than not used to obfuscate the mode in which a tool or system works. The technology becomes a ‘black box’, disclosing no knowledge of its inner workings to users. This is problematic, because it essentially excludes policy makers, citizens, activists from understanding how a technology works and thus holding the company or service to account. Especially when decision-making is delegated to automated systems, it is fundamental that we as societies can understand the mechanisms and data the decision is based on. Delegating predictive policing, automated handling of social benefits, health care decisions and the like to automated decision making systems requires that these systems have some level of transparency. Otherwise, they cannot be monitored and held accountable.

There is a sketch called ‘computer says no’ in the British comedy television programme Little Britain, where Carol Beer, a bank worker and, in later sketches, a holiday rep responds to a customer’s inquiry by typing it into her computer. She then responds “computer says no”, no matter how reasonable the customer request is. Little Britain started the sketch in 2004, when “computer says no” was still a slightly absurd way to answer a request. With an increasing number of social services and more and more of our daily interactions shifting to automated decision-making, it is frightening to see how many decisions are explained away this way. And because the deciding system is essentially a black box, it means that the decision cannot be challenged. This is why we prefer to work with open-source technology and develop our systems along the guiding principles of conviviality, where access to knowledge about a tool, technology or system is a given.

Olga:

I absolutely agree that open-source technology should be the standard. But I think opacity, as Édouard Glissant frames it, would in relation to technology rather be something the ‘user’ (also an outdated concept) should be granted, something they have a right to, instead of having to hand over all their data and trajectories, in order to have access to a service. For Glissant, opacity is a decolonial tool. Of course, it cannot be used top down, then it becomes intransparency and can even be authoritarian. That’s why the concept is so interesting to me because it is so depending on context.

der Kulturen der Welt Berlin in September 2022© Laura Fiorio

Felix:

Open, collaborative processes are often imagined to be quite harmonious, but in practice, as we all know, they can be quite conflictual, and there are always practices of inclusion and exclusion.

Olga:

In open processes like the New Alphabet School, where any three or more people together could submit proposals to teach, we also needed to ensure that no discriminatory practices become part of the school or that there are no fact denying positions in the program, for instance in relation to the Covid 19 pandemic. This is why the work of the jury in the New Alphabet School was not just one of selecting proposals in a yes or no manner, but the jury really took care and curated the positions it selected, entering a process of collaboration. There were long conversations with workshop conveners how to set things up and they were provided feedback. In one case we excluded someone from the school who did not comply with our code of conduct, because he submitted a proposal naming two other people as his collaborators who had not been aware of this. But it is possible to include contradictory and critical voices, also in relation to us as institutional workers, to listen to them and also publish them on the blog with their respective perspectives, when a lot of time and care is put into the conversation to make arguments stronger or more fact-based.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

For any collaboration to work, there needs to be a basic agreement on certain rules or guiding principles. This may require positioning and excluding certain other options, ideas or collaborators. In our view, if this is done deliberately and in a way that is transparent, it enriches and strengthens the project. When it comes to technologies, there is also a balance to be struck between openness, inclusivity and achieving certain project results. If you are designing a website for an exhibition for example, you choose to use certain code, certain functionalities, certain data-types, which in turn will be more or less inclusive to publics in The Global South who may be accessing the website from older devices and with less bandwidth. So, we’d say that in any project there are certain social and technological protocols that shape accessibility. Choosing those protocols means defining a position from which to relate to others.

Felix:

Many of the approaches you both describe have an element of collective self-education. Whom does the research address?

Olga:

What is often criticized about the self-organized research and instituting practices in the arts is that they do not publish outcomes and results and hence people who have not been part of the processes are excluded. They also cannot reference them as research positions. In that sense the schools for self-education remain opaque for outsiders which can be seen as elitist circles of confidentiality, sometimes even intimacy. There is a lot of dissent and conflict within the schools, but this is usually not accessible from an outside perspective so the schools can look like places that are built on pre-existing assertions or agreements that are not questioned. This has to do with a question of scale. Because the schools are not universities and they are certainly not state institutions, but rather enable processes of what Markus Messling calls a minor universality. Markus Messling writes that after the end of European universalism as an imperial project, universality as a planetary scale needs to be defended by addressing it from a very localized and specific struggle, from the margins or from a minoritarian perspective. This is a universality that is created bottom up and not exported top down as European universalism historically was. What is also important in this context is what Isabell Stengers calls a “minor key” (2005: 187). The schools I study for my PhD research are decidedly small and do not scale up to large institutions. This is what I call a permanently preliminary institutional form. Rather than assuming one can make universal claims or found a new uni-versity, published results of these pluri-versities or para-versities or anti-academies often take the shape of a montage of different takes and voices which is great, but it also means that the schools are hard to argue with. However, they do offer points of relation for other marginalized perspectives and that’s where their “minor universality” lies. It’s true that we can get the impression of a closed circle or bubble rather than the general public being addressed. But maybe the idea of addressing everyone is always an illusion and institutions always create their public or counter-public realms as specific social spheres around them.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

This is a really interesting point. In many ways the same universalism is at play when we look at how technologies are developed. It is mind-boggling that most of the technologies we use are the same all over the world – with few exceptions. When critically examining technological developments, we are often confronted with the notion that technological development is determined and that the media and the tech we have is exactly what we need. But does tech development necessarily need to be driven by innovation and profit? What would it mean to develop technologies for de-growth? What would technologies look like that were tailored to the specific social spheres around them? Maybe our technologies, but also our exhibitions, our learning environments could be more convivial and specific to our contexts without becoming illegible to other contexts.

Conviviality is a term coined by Ivan Illich in the early 1970s and used to think about alternatives to universality, both in regard to schools or the production of knowledge and technologies. The scholar Andrea Vetter describes dimensions of convivial technologies that could also work for curatorial formats: Relatedness (how does something integrate into a complex system of human relations, infrastructures, knowledge), Accessibility (can we access both the materials and the knowledge needed), Adaptability (is use voluntary and is it scalable) and Appropriateness (can we use locally available knowledge, materials and aesthetics).

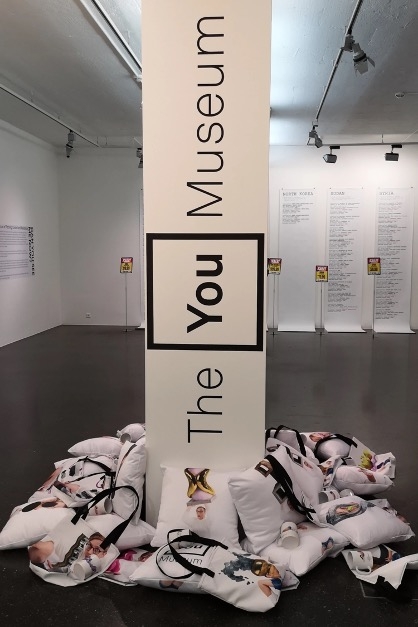

Yours, Ours, Drugo More Rijeka, 2023. Photo: Tanja Kanazir /

Drugo more

Felix:

For me, this points to the deep relationship between form and content, or, slightly differently, between the format and the possibilities of knowing. This also indicates that there is not one format of knowing, but questions and approaches necessitate different formats, from the very process-oriented to the very representation-oriented. This raises the question of the relationship between doing and showing.

Olga:

Curatorial research takes place on the level of doing together, which cannot be extracted and shown in the context of an exhibition. This overthrows the logic of the universal museum or exhibition that claims to be able to display any given aspect of the world as re-presentation. I am interested in how museums and art spaces can develop new formats that allow visitors to join in the doing rather than to look at representations of things done. This implies a lot of change within cultural institutions. You can no longer have the curatorial team develop the research which is then handed down to an educational department which then in turn creates educational formats for the public. Museums used to have small educational departments with people doing the guided tours, but now whole institutions are rethought as places of education and mediation, where this is their main purpose.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik:

For us, the difference between ‘showing’ and ‘doing’ is not as important as the difference between ‘showing-doing’ and ‘speaking’. Many of the works we show in exhibitions have already expanded the exhibition format from a representational show, into a more active and inclusive process that encourages doing. Look at Simon Weckert’s work Google Maps Hacks (2020) for example. In this work, Weckert takes 99 smart phones for a walk through the streets of Berlin in a handcart. The phones are all connected to Google services, and thus Google Maps interprets the data the phones emit as a traffic jam. Because usually 99 phones moving slowly down a street signifies 99 cars moving slowly. Google Maps marks the street red and reroutes all other cars to avoid the area. The video installation of the work acts both as a documentation of the performance and an instruction for doing to the viewer. Weckert does not obfuscate the technology but rather makes its workings visible.

Understood in this way, both showing and doing require the messiness of involvement and engagement. The artist, and in extension also the recipient, needs to get their hands dirty, probe and prod the systems they are dealing with. On the other hand, speaking requires distancing oneself. Speaking may even require a level of analysis and sorting that carries a degree of violence. Speaking requires a different temporality and it requires the extraction of knowledge, the drawing of conclusions. Speaking is of course a very important activity – but when we are dealing with contemporary technologies, it may require that we collapse the multi-facetted view that we aim for in our curatorial practice.

References

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Janez Fakin Janša, (un)real data☁️ - (🧱)real effects, Aksioma, Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana forthcoming in 2024

Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse. Selected Essays, [Le Discours Antillais, Paris: Les Editions du Seuil 1981], transl. Michael Dash, The University Press of Virginia, 1989.

---, Poetics of Relation, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997 [Poétique de la Relation, 1990].

---, Philosophie de la Relation: Poésie en étendue, Paris: Gallimard 2009.

Trinh T. Minh-Ha, Woman, Native, Other. Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, Indiana University Press, 1989.

Markus Messling and Franck Hofmann (ed.), The Epoch of Universalism 1769-1989 / L’époque de l’universalisme 1769-1989, Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter 2020.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons, Fugitive Planning & Black Study, New York: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Frank Pasquale. The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Olga Schubert, “100 Years of Now” and the Temporality of Curatorial Research, The Contemporary Condition 11, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018.

Isabelle Stengers, “Introductory notes on an ecology of practices,” in: Cultural Studies Review, vol.11 Nr. 1 (March 2005): 183–196.

Valentina Tanni, Exit Reality - Vaporwave, Backrooms, Weirdcore, and Other Landscapes Beyond the Threshold, Ljubljana: Aksioma, 2024.

Brad Troemel, “Provocative Materiality in the Valley of Death,” in: Peer Pressure, Brescia: LINK Editions, 2011.

Andrea Vetter, “The Matrix of Convivial Technology – Assessing technologies for degrowth,” in: Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 197, Part, 2, 1 October 2018, Pages 1778-1786.

Curatorial and artistic projects mentioned

New Alphabet School at Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin (2019-2022) https://archiv.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2019/new_alphabet_school/new_alphabet_school_start.php

Can You See Me Now? at AIA Zürich (2022): https://.bitnik.org/cysmn

Unreal Data: Mine, Ours, Yours at Drugo More Rijeka (2023): https://drugo-more.hr/en/mine-yours-ours-2023/

Unreal Data – Real Effects (2024) at Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art Ljubljana: https://aksioma.org/unrealdata/

Latent Spaces Research Project: https://latentspaces.zhdk.ch/

Let’s Play: Brexit Reality with Total Refusal and Valentina Tanni, Slovenska kinoteka, Ljubljana https://aksioma.org/unrealdata/performances/lets-play-exit-reality/

Tega Brain, Unfit Bits, 2015: https://tegabrain.com/Unfit-Bits

Simon Weckert, Google Maps Hacks, 2020: https://www.simonweckert.com/googlemapshacks.html

Jeremy Bailey, The You Museum (2015 / 2022): https://www.theyoumuseum.net/about.html

Biographies

Felix Stalder is a professor teaching Digital Culture at the Zurich University of the Arts. His work focuses on the intersection of cultural, political and technological dynamics, in particular on new modes of commons-based production, copyright, datafication, and transformation of subjectivity. He not only works as an academic, but also as a cultural producer, recently retired as a moderator of the mailing list <nettime>, a crucial nexus of critical net culture. He is a member of the World Information Institute and the Technopolitics Working Group, both based in Vienna. He is the author/editor of numerous books, among others Deep Search. The Politics of Search Beyond Google (Transaction Publishers, 2009), Digital Solidarity (PML & Mute, 2014), Kultur der Digitalität / Digital Condition /字 状况 (Suhrkamp, 2016/Polity Press, 2018, School of Public Art, 2023), Aesthetics of the Commons (Diaphanes, 2021), Digital Unconscious (Autonomedia, 2021) and From Commons to NFTS (Ljubliana 2022). → http://felix.openflows.com

!Mediengruppe Bitnik (read - the not Mediengruppe Bitnik) are contemporary artists working on, and with, the Internet. Their practice expands from the digital to physical spaces, often intentionally applying loss of control to challenge established structures and mechanisms. !Mediengruppe Bitnik’s works formulate fundamental questions concerning contemporary issues. They have been known to subvert surveillance cameras, bug an opera house to broadcast the performances to the city, send a parcel containing a camera to Julian Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy in London and physically glitch a building. In 2014, they sent a bot called «Random Darknet Shopper» on a three-month shopping spree in the Darknets where it randomly bought items like keys, cigarettes, trainers and Ecstasy and had them sent directly to the gallery space. Their works are shown internationally and are part of public and private collections, among others at the House of Electronic Arts Basel, Kunsthaus Zürich and the Servais Family Collection Brussels. They have received awards including the Swiss Art Award, PAX Art Award, Prix de la Société des Arts Genève, the Golden Cube at Dokfest Kassel and an Honorary Mention at Prix Ars Electronica. !Mediengruppe Bitnik are Carmen Weisskopf and Domagoj Smoljo. https://.bitnik.org/

Olga Schubert was the initiator, co-curator and project leader of the collective learning and artistic research format New Alphabet School (2019-2022), editor of the publication series Library 100 Years of Now and curated the lecture series Dictionary of Now at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. She continues to work at HKW and freelance with Julia Grosse (Contemporary&) as an editor for publication practices. She is currently the recipient of the Dissertation Completion Fellowship of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Junior Research Fellow at IFK International Research Center for Cultural Studies Vienna and a PhD candidate at Kunstuniversität Linz, where Karin Harrasser supervises her dissertation "Curating Opacity and Coevalness. Alliances between Decolonial and Post-Soviet Anti-Academies after 2000”. Previously she worked in curatorial teams for the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden, the Grimmwelt Kassel and the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst Berlin. Her publications include Wörterbuch der Gegenwart (with Bernd Scherer and Stefan Aue, 2019), 100 Years of Now and the Temporality of Curatorial Research (2019) and Glossar inflationärer Begriffe (with Sara Hillnhuetter and Eylem Sengezer, 2013).