At the end of 2023, artist and researcher Rik Fisher participated in a Walking Residency organised by ReRouting (RR) in partnership with Co-Making Matters (CMM) initiated and curated by Viviane Tabach. CMM’s container space at Haus der Statistik (HdS), a building in the centre of Berlin that until recently was an empty relic of the GDR, acts as a residency base for reflection, whilst the surrounding streets become the studio and site for research.

ReRouting is a project based on research-through-motion that explores the potential of walking as a curatorial space for exchange and encounter. Initiated by curator Clementine Butler-Gallie, the project takes walking as both method and metaphor to question and rethink how we perceive space for production, research and presentation.

This is an edited version of a conversation between Rik Fisher and Clementine Butler-Gallie, that took place through an exchange of text over a month, acting as a reflection from this residency period and offering a meandering map of how walking enters a practice.

CBG: Rik, it has now been a few months since your time at the Walking residency. Your practice has engaged with walking as a research method and theme for some time and so I am curious to hear more about how you entered into or departed from this residency structure. How did it differ from your usual ‘studio’ / walk routine?

RF: My usual routine can vary a lot, it depends on what I'm working on. But one constant is that it nearly always involves walking (in its various forms including wheeling, stumbling etc.) as research in some way. To give an example, for a period of three years I walked around a specific area of Berlin, using longitudinal documentation (or repeat photography) to record various graffiti. I then created and facilitated a participatory group walk visiting some of these locations and using the graffiti as a prompt to open up dialogue on various issues. This idea, like most of mine, came from a simple walk and what that can reveal.

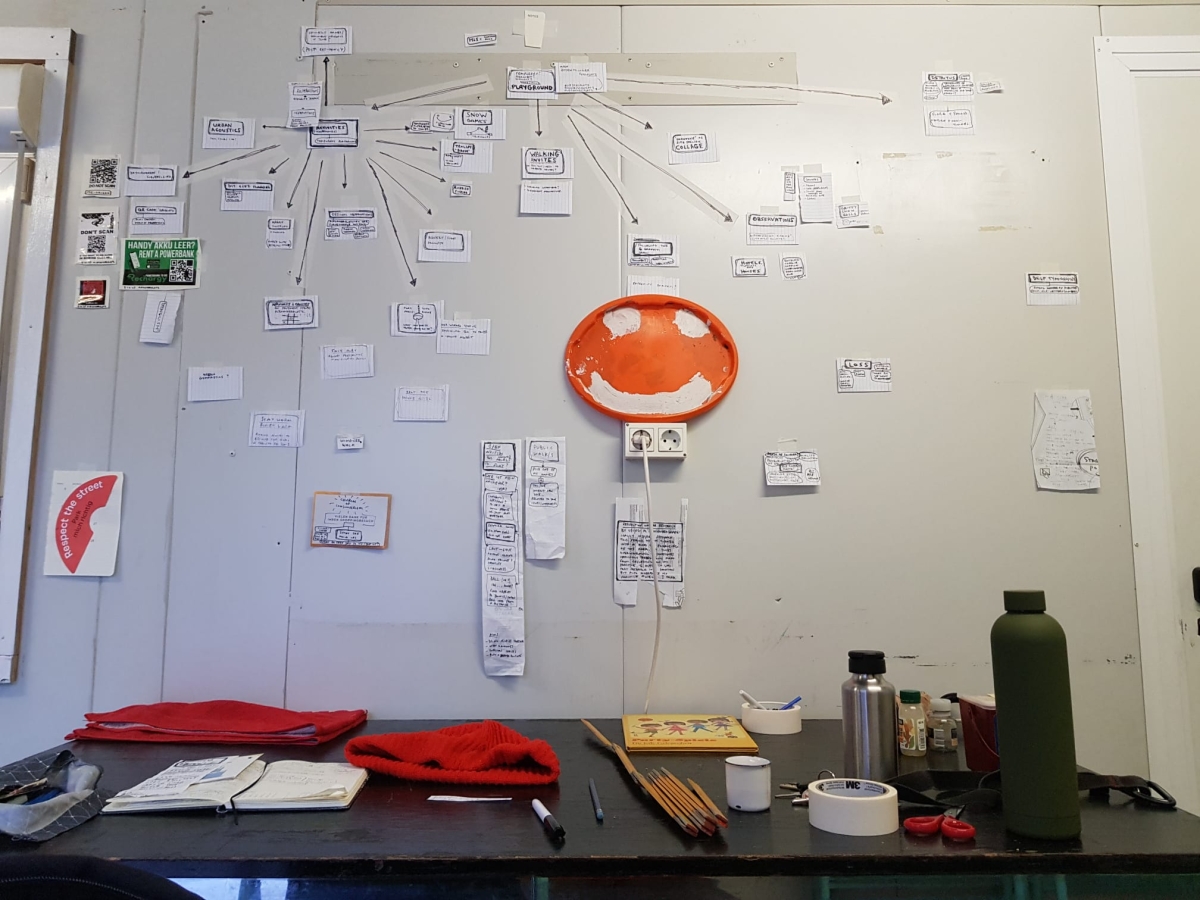

A big privilege of the residency format for me is consistent time and also studio space to focus and reflect (things that some people take for granted). This is a wonderful thing, especially for me after my practice has had to alter since becoming a parent. Physical space can be precious and being able to turn a wall into a giant mind map during the residency was useful, not only because I often work visually, but to be able to move things around and also to be able to try to explain to others, what was going on inside my head.

I guess an idea of a residency is that it in some way breaks the routine (and potentially makes new ones) of whoever is participating in it. Also in my practice, as it is inspired by the Situationists and psychogeography, this breaking of, or questioning, routine is a useful tool that opens up opportunities to become critical.

Walking, and loitering (which I also did a lot of), does help to connect to a place, not just through human, transport and architectural aspects for example, but a wider whole, including fauna, flora and even rubbish. The change in routine here was multiple. For example, I loitered around Alexanderplatz for extended periods, repeatedly for several days, to the point where I was wondering if the police were going to finally ask me what I'm doing. This allowed me to explore the area deeply. Which, coincidently, reminds me of Nick Papadimitriou's approach to walking, 'deep topography'1.

I fell into a kind of routine. I always began each day arriving into Alexanderplatz on the U-bahn, wove my way through the underground station, sometimes stopped and sat down for a coffee, to do the opposite of most people in the station and then randomly picked one of the many exits to leave up to street level. I always surfaced somewhere around the middle of Alexanderplatz and from there the day went off in its own direction. The only constant being that I returned to the studio space to reflect or plan... or to dry off.

CBG: The questions of who is walking where and why, what one is observing along the way and what that says about an area, and a site’s social dynamic are vital groundings to the walk as a research method. It also raises an important point, especially within a curatorial context, of how the way one walks reflects or affects what is perceived as a ‘walking space’, for example the privilege or necessities of the flâneur vs the vagabond.

As there are many ways to walk, there are also many ways (or reasons why) one can loiter. I also find your mention of loitering in relation to Alexanderplatz particularly interesting because the area in the context of Berlin is seen as the middle ‘Mitte’ point, yet it is a bit of a transient place. People often travel through the area, not to forget its proximity to Friedrichstraße which was the place of transit between East and West during times of division. But to spend time there, particularly in the loitering sense, is something else. To wait around or move without clear or obvious direction is of course a big element of many research processes, at least I very much relate to that. The short format of the residency was intended to create a small shift in the participant’s regular rhythm, and there is no set expectation to produce or walk with a clear intention - simply thinking about walking or walking whilst you think could in fact be part of the walking residency.

RF: I can see how the focus on walking in the residency could be a shift of rhythm for many participants. For me, with my practice already being rooted heavily in walking and spatial practices, the main rhythm change was that the residency allowed an intensity to my research and practice. Also having access to the studio did give me a base, a place to revisit, rest, contemplate and become focused.

As you said, the site of Alexanderplatz and the surrounding area were obviously very important to the residency. There is a lot of history that should be acknowledged. And with the TV tower (Fernsehturm) often in sight, it's hard to forget that you're in an internationally renowned, iconic place.

Specifically on the location of HdS, I read that it used to be a care home for older Jewish people. I was reminded of this when I stumbled across a memorial that triggered stories to be read through speakers as you walk by it on the street. I think this memorial was installed by an artist who continues to work with the local neighbourhood exploring and remembering this history2.

Another form of memorial that I would see when walking around were the ‘Stolpersteine’ (translated into English as ‘Stumbling stones’) in front of some doorsteps where previously residents lived, before being forcefully removed and mostly murdered by the Nazis. These are a common sight across Berlin3 and an important way to remember how history has shaped lives and landscapes.

I also stumbled across unexpected links, for example as I walked down the road from the memorial, I mentioned I noticed the Bürgeramt flying the Israeli flag. Considering Germany’s history, this was obviously a statement of solidarity and in relation to the Hamas attacks at the time. However, since this happened Israel attacked Gaza and many more people have been killed. It is a difficult subject to discuss and has a long and complex history, but it is not safe to silence it, which it seems it is to some extent here. It needs to be discussed and something must be done. For me this uncovers how the streets show connections, even internationally, and they speak volumes in many ways.

Back in the GDR people spoke about the walls listening in. HdS and Alexanderplatz were previously GDR centres of surveillance, to collect and store data on people and their actions. So, the irony of me being there and observing the area was not lost on me. Not that all loiterers need what they do to be academicised, but here I was loitering as research.

As you walk through the large shopping centre on Alexanderplatz called Alexa, you can almost feel the GDR turning in its grave. It's a real capitalist spectacle to be somewhere like this, it might be normal for a lot of people, but to be there as part of a residency made it even more surreal. As I found out, in the morning people can enter the shopping centre and wait around before the shops inside open. Then at a certain time you hear a bell chiming and a person announcing that the shops are opening, with the bells ringing and the masses of people it feels like you are in the church of consumerism. Buy buy buy! Almost reminiscent of John Carpenter's film 'They Live'4 and the sunglasses that reveal what's really happening, although instead of sunglasses, the residency was my lens.

Despite all this, HdS still holds some socialist values. You can read in more detail about the history elsewhere5, but because of the protests and work of a number of creative and community groups they managed to somehow get the state to buy back the HdS building and agree to turn it into much needed social housing and a community and art space. This is all in process now and is why the studios are temporarily in containers outside the building, creatively using the space around the building. So, although we lost the 'cool' looking windowless front (apparently made windowless on purpose to reduce vandalism) of the building with the iconic altered sign 'Allesandersplatz' (translated roughly to ‘place where everything is different’) and the giant painted letters spelling 'STOP WARS', HdS is changing for the better. Perhaps like the socialist ghosts could not be fully chased out by neoliberalism?

Coming back to loitering. Perhaps this is something viewed as static, not as a walking practice, but as is always the difficulty with this mix of terms and practices, loitering is inherently linked to what I do, and to my approach to spatial practices and psychogeography. Ralph Rumney (ex-situationist) talked about this in the interesting book 'The Map Is Not the Territory'6 and called this 'static drifting', something that a member of Wrights & Sites later used as part of their film '4x4x4'7. And take Georges Perec for example, he wrote a whole book on sitting down in 'An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris'8. It can become overwhelming, as well as inspiring, to loiter. When the world opens up before your eyes you start to see how much of it you are missing in your rush. Psychogeography aims to break routine, to notice, question and possibly change.

CBG: It definitely feels like you noticed a lot in the area, I hadn’t come across the plaque for the Jewish care home before. This acknowledgment of sitting, resting, not necessarily doing anything at all, as an equally important aspect of research, particularly walking research, reflects something of the format of this particular residency. A container space is offered to residents, so one could question how this offer is different from a standard studio residency. But the offer of a base responds to the fact that this practice of ‘sitting’ often accompanies a walking practice. The term ‘residency’ insinuates staying-put, to be in residence, to live somewhere, at least for a period of time. Walking implies the opposite, one is on the move, in motion. So, a ‘Walking Residency’ is somewhat of an oxymoron, but I think that opposites meeting enters so much of practice-based artistic research.

I want to jump back to this ‘loitering as research’ and how you highlight that we don’t always have to academicise the everyday. I often reflect on this when building or conceptualising curatorial structures and projects - how can the complexities and the rhizome effect inherent in so much of research be simplified, and how can seemingly simple frameworks reveal their layers? For me, walking as a departure point encapsulates both of these - it allows a de-academisation of the curatorial through the simplicity and everydayness of walking, yet within the motion the multiplicity can unfold.

RF: Terminology can be exhausting. The Situationists discussed this and aimed to make their revolutionary praxis an everyday one, not one separated off into inaccessible terminology or divisive specialised forms. So, yes, we don’t always have to academicise things as this can create barriers to access and also continue power imbalance, but if we don’t ask questions and unravel these complexities (i.e., using critical or radical theory), there is a danger that we oversimplify or are not aware of important factors.

I previously studied for a master’s degree in social work in the UK, it was an absolute privilege to do so. Traditionally, in the past, social work courses in the UK had a radical focus (radical meaning challenging the culture and status quo, aiming to bring systems of oppression to an end through advocacy, community organising, and direct action. Radical social work also seeks to empower individuals to participate in creating social change and self-advocacy). However, more recently, the UK government funded many 'fast track schemes', one of which they called 'Frontline'. With the premise that students can be taught practical methods fast, graduate quickly and earn a large wage. The problem is that this actually has a political agenda, it side tracks critical theory and therefore politics, creating social workers who do not question the system, or recognise systemic issues. Education, like everything, is not neutral.

With some forms of education, we are encouraged not to question and this can also be the case as we walk down a street. We encounter signs telling us not to enter or not to play ball games etc. So, what happens when we choose to ignore this, when we explore spatial practices as critical opportunities? Some recurring collective experiences of mine have been through the Loiterers Resistance Movement9 and Berlin Diversion Agency10. In relation to education, my practice often takes critical pedagogy and group consciousness raising as inspiration. As in, we can all learn from each other, something I have researched with Paulo Freire's11, bell hooks'12 and Mark Fisher’s13 approaches.

CBG: The question you posed about what happens when we ignore signs that don’t allow entry takes me to the term or act of trespassing. I have recently been thinking a lot about what trespassing as a curatorial act can mean, particularly in relation to the hierarchy and elitism of access to space or the pseudo-publicity of sites (both in relation to art and everyday settings), but also linked to censorship and cancel culture that can exclude space for debate and dialogue. How do we enter places we may not be wanted or invited? In the late 18th and early 19th century in the UK The Enclosure Movement14 saw common land, of which there used to be lots across the country, sold as private property. In response to this, groups of men and women would gather, calling themselves Ramblers, to trespass on the land as a simple act of protest. There is something about trespassing with others that gives an additional sense of performance but also of intention. I’d love to hear more about your experiences of walking with the LRM and BDA groups - did you ever trespass? and how did the collectivity, or walking together with others, compare to the times you have walked alone as research?

RF: Access and trespass are big topics for me. They raise questions around physical access, which can take many forms, from wheelchair access, to the housing crisis, to gentrification. How does it affect people when their needs aren’t part of the process of planning (whether that be urban planning, art projects or something else), but just an afterthought or tick box exercise, if not forgotten completely? Talking of gentrification and the privatisation of land opens up the topic of trespass, the less land that is public, the less land we (legally) have access to. Obviously, we have weird in-between spaces, like the Alexa shopping centre for example, which is open to the public, but with conditions and with its own private policing. It seems we are getting more and more of these types of spaces. Access also relates to subjectivity and intersectionality15. All of this also changes as we move through space. But using theories and lenses such as black feminism for example, this allows us to consider intersecting oppressions, unravelling power and privilege.

In regards to trespass and the Enclosure Movement, this act of collective power through trespass is important. My example of this growing up in the north of England was the mass trespass of Kinder Scout in 193216. However, this is not something of the past, it continues to this very day and laws around the right to roam need fighting for17. Showing that walking can be an important tool to protest. Again, this all links in with what I mentioned earlier - group consciousness raising, so not just the number power of people coming together, but also the other potentials that this opens up. This is something explored by the Loiterers Resistance Movement (LRM) and Berlin Diversion Agency (BDA).

Both groups were inspired by Situationist praxis and specifically psychogeography and the ‘derive’ or ‘drift’. If I’m correct, the LRM was set up back in 2006 by a Manchester based collective that wanted to use psychogeography as a way to explore the streets. Thanks to a massive commitment by Morag Rose, around eighteen years later the LRM still meets once a month to do a group drift around Manchester and Salford. As I mentioned, I took part in some of these when I lived in the area.

When I moved to Berlin, I found nothing like it. I considered this and decided to create something like the LRM, but different, inspired not only ny the Manchester collective but also by a number of other things. It was an experiment, something new, with the flexibility to change to the collective’s needs and search for ways to practice something that was playful but also meaningful. So, with the need for a name, I came up with Berlin Diversion Agency (BDA). BDA is an experiment in collective spatial explorations, working with various approaches, with an aim of being critical and radical. As with most of my practice and projects, we are using walking as a means of experimental pedagogy and group consciousness raising. The collective element opens up diverse subjectivities and narratives, so the streets really do become layers unravelled and unsilenced. Which I find a fascinating approach to research.

CBG: Can we return to the residency and hear about how that process of mapping ideas worked for you, between your walks and the wall of notes? It is included in the invitation to the residency that a public walk can be organised together - whether this be a walk, an artist talk, a reflection or a more conceptualised offering. This is not an expectation, as it is not a production residency, but simply a route left open to the artists. Do you have any plans to continue with the research and ideas that emerged during your walking time?

RF: Yes, the mind mapping was initially a way of collecting thoughts and focuses after walks. I find it very helpful to work visually in this kind of way and it can help to describe to others. It helps me to log or remember things and find connections. Exploring and unravelling how things are, how they are not, or how they could be interlinked. Mind maps are something I have worked with when I have the space and I didn’t really consider it much, until getting comments from people who saw them and also coming across other people using mind mapping in interesting ways, such as Moses März’s decolonial cartography18.

Mapping has traditionally been used by and for those in power, so I find it fascinating to use it as an alternative narrative or critical tool. There are many examples of this and it can touch on some really interesting topics and approaches. For example, countermapping as used by William Bunge who worked with communities to raise awareness around social injustice19.

It’s really enjoyable to be able to talk about the residency and I want to focus on one aspect you mentioned, gathering objects found on the walks. I had an idea previously that was lingering in my head and the walks repeatedly bought me back to this focus; exploring the idea of taking objects out of their environment. But also thinking about what would happen if these were then sold or commodified, for example as a badge.

I found myself having extended continuous trails of thoughts as I walked. It's a dense topic, coming from simply picking up something, which would be considered rubbish by most people, and presenting it differently, exploring its story and how it speaks to us. And smells to us sometimes! A lot of questions arose, some very unexpected. For example, finding a healthcare card and considering ethics and your civic duty to return this or not. Turns out it had expired, but still, should you return it? Did I?

And for those who might be sceptical, in its defence, this is a form of research, a kind of archaeology, like 'gleaning'20 or 'mudlarking'21. There were also some things that were literally stuck in the streets, that I would have had to arrange a mini archaeological dig to retrieve (see below). Walter Benjamin also talked about the ‘ragpicker’22 and how these people who picked unwanted objects off the street were in a way using what capitalism rejected.

Some of these found objects got turned into sculptures of a kind, that I then hung in the window of the studio. I had several thoughts around this, one being that it might interest passers-by, open up their thoughts or even encourage them to knock on the window and speak to me. These found objects included a broken pair of glasses, that were fun to alter your vision with, and the pairing of a metal bar and stone, which made a nice chime. The objects became a kind of assemblage, taken from the streets to reflect and prompt thoughts.

Back to your question about considering future plans from what emerges from the residency…

As you mention, there is a possibility of doing a public walk in the future. This was definitely something I kept in mind during the residency. I wanted to embrace the luxury of having no expectation to produce something, but as HdS states it exists for the “common good” and because my practice explores elements of participation and terms like ‘socially-engaged art’, I did put pressure on myself to think what would be interesting or potentially useful for people living in the area. But this is not much use if you’re not actually communicating with people living locally. This is always a good way to question your own practice and research. Such as, is it useful? Are you representing anyone? Are you speaking for anyone? Other than the potential for follow-up, public walks, I felt the residency was rich in other ways, that it opened up many topics and if the opportunity (or funding most likely) arose I would like to document this in some kind of zine or book, so that could be shared and discussed, perhaps with local residents? Perhaps this is a possibility through HdS and their art/community space when it is finished?

Biographies

Clementine Butler-Gallie works in the field of curation, arts education, and artistic research with a focus on constructing future spaces for and learning from past stories of cultural exchange and encounter. She is the initiator of The ReRouting Project and other current roles and projects include editor of JAWS journal, editor of the publication ‘They:Live - Manual for Social Art Practice’ published by nGbK Verlag in Summer, 2024, and part of the curatorial team for the interdisciplinary project ‘Dissident Paths: Walking Together as a Method’ at neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst (nGbK) in 2025/2026. See more here: https://clementinebutlergallie.com

Rik Fisher (they/he) has a background in DIY music, social work and mental health advocacy. Their research and practice aims to explore, question, open dialogues and transform through participatory projects, exploring spatial practices inspired by approaches such as psychogeography and also experimental, critical and radical pedagogies.

Rik writes and talks about their research and practices through publishing zines/books (Ambulant publishing), Journal essays and presenting at various conferences/events.

Rik’s solo and collaborative practices include walks, interventions, performances and more. And has had work exhibited, for example, as part of ‘Walk!’ a collection of work from international walking artists at Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt.

Rik founded Berlin Diversion Agency and co-founded the international collective [Per]mission to Play. Both collectives continue to actively explore various forms of critical and radical spatial practices.

Email: [email protected]

Instagram: @rikfisher

- 1There are various videos on youtube about Nick Papadimitriou and the approach termed 'deep topography' e.g. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnW1XDo7usI

- 2For more information on the history and project visit online: https://monumentlab.com/bulletin/one-site-layered-histories https://www.rsteinwexler.com/projects/fuegungdesschicksals

- 3Stolperstein or Stumbling stone as a memorial. More information online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stolperstein

- 4'They Live' Film directed by John Carpenter. Released 1988.

- 5More information online: https://hausderstatistik.org

- 6'The Map Is Not the Territory' by Alan Woods. Published 2001 by Manchester University Press.

- 7'4 x 4 Screens' Wrights & Sites. DVD released in 2013 by Live Arts and Development Agency (LADA).

- 8'An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris' by Georges Perec. Originally published 1975.

- 9Loiterers Resistance Movement (LRM) for more information visit the website http://thelrm.org

- 10Berlin Diversion Agency (BDA) currently has no online presence. For those interesting in joining or with any questions please email [email protected]

- 11See 'Pedagogy of the Oppressed' by Paulo Freire.

- 12See 'Teaching to Transgress' by bell hooks.

- 13This is in reference to the lectures given under the title 'Post-Capitalist Desire' as taught by Mark Fisher at Goldsmiths University. Fisher used an open approach asking students to be involved in directing the course. A former student of his, Matt Colquhoun, turned the transcribed lectures into a book, published under the same title 'Post-capitalist Desire' by Repeater Books 2020. See also ‘Egress: On Mourning, Melancholy and Mark Fisher’. Mark Fisher’s students continue this legacy on in different ways. E.g. see For K Punk https://4kpunk.wordpress.com, walking related project Incursions https://www.incursions.uk and Matt Colqhoun’s website/blog here: https://xenogothic.com

- 14The Enclosure Movement in Britain, more information online: https://www.thelandmagazine.org.uk/articles/short-history-enclosure-britain (accessed 14.03.2024)

- 15Intersectionality, as explored by Audre Lorde, can be defined as the study of overlapping systems of oppression or discrimination that stack against individuals of different races, genders and sexualities. See ‘Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches’ (1984).

- 16Mass trespass of Kinder Scout, more information online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_trespass_of_Kinder_Scout

- 17Here is an article exploring Labour’s recent U-turns on right to roam laws and fighting this in Dartmoor, UK. See online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/feb/19/mass-trespass-dartmoor-england-right-to-roam-laws

- 18Moses März’s decolonial cartography. More information online: https://12.berlinbiennale.de/artists/moses-marz/

- 19William Bunge’s Countermapping. For example see online: https://civic.mit.edu/index.html%3Fp=220.html https://adventureuncovered.com/stories/meet-the-counter-cartographers-using-maps-as-a-tool-for-social-change/

- 20For example see the documentary film 'The Gleeners and I' Directed by Agnes Varda. 2000. France.

- 21Mudlarking. For example see online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mudlark

- 22Ragpicking. See for example page 63 in ‘Everyday Life and Cultural Theory’ by Ben Highmore. Published 2002 by Routledge.