My roots

I speak from my father and my mother. I speak from Nayru.

I speak from Nueva Atzacoalco, north-east of Mexico City, and from Santa Úrsula Coapa, to its south.

I speak from Yuri, Natalia, Marina and Francisco.

I speak from the National Autonomous University of Mexico and from public and free education.

I speak from a body that hurts.

I speak from the Graduate Unit and the Faculty of Arts and Design.

I'm talking from public transport and from a pink Nissan March.

I speak from the open sea and the Marlboro Crafted.

I speak from the wound of academia.

The substrate

Five years ago, I was about to enter the Doctorate in Arts and Design, a program belonging to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM), where I have completed all my higher academic training. I was interested in knowing how what is called "artistic research" was carried out.

Even though there are references from other latitudes, mainly European, the context implies important determinations in its doings, so I decided to focus on investigating my particular context, the doctoral research in arts at UNAM. Now I understand that, in reality, I was inquiring about my own doing, I was looking for myself and my place in the world. In the end, despite the classic notions of objectivity and neutrality that exist in academia, what do we investigate if not what affects us, what touches us, what hurts us? questions that lead me to the idea that, beyond checking or validating data, it is important to present the processes that lead to specific results during our own investigations.

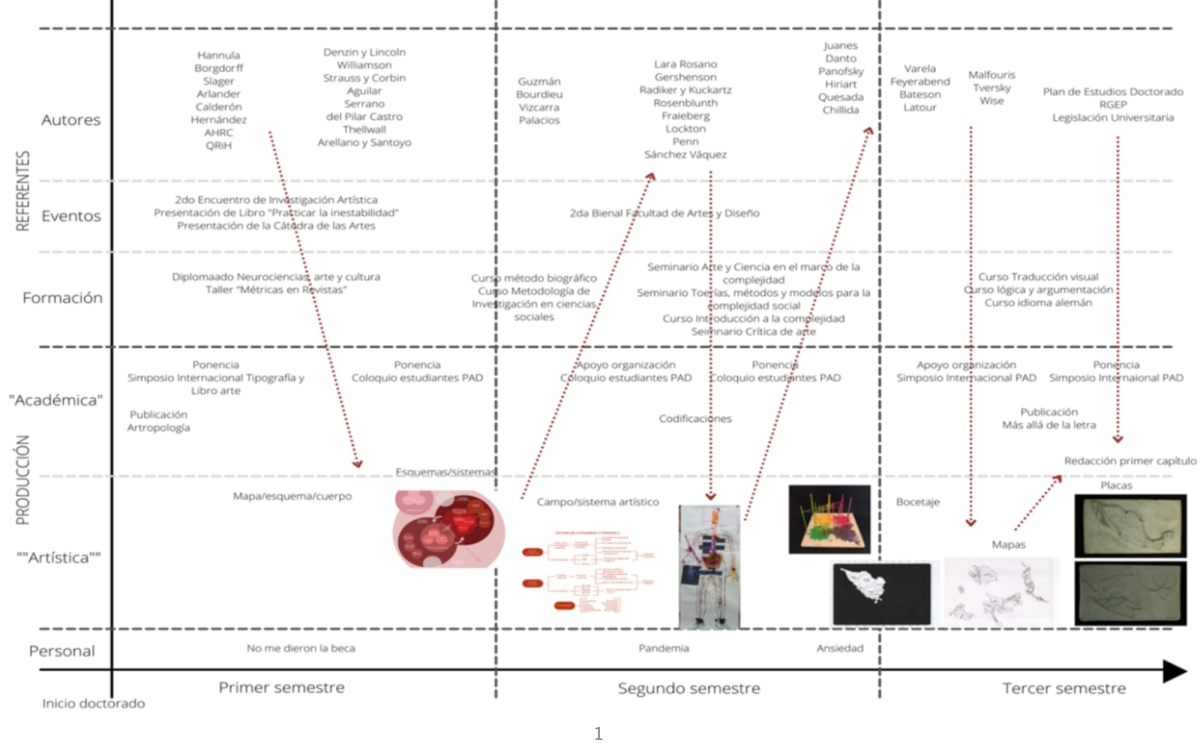

In that vein, I began to obsessively record my actions and graph them. The first approach to this journey was made under a temporal scheme that divides the "academic" dimension from the "artistic" dimension (Figure 1). This division, as I will explain later, will be diluted to give way to a more global understanding of research. However, at that moment, that first visualization gave me the initial clue to question in what ways we can talk about our processes?

The Postgraduate Program in Arts and Design (PAD) of the UNAM, one of the most recognized institutions in the country, has its most remote origin in the Academy of San Carlos, which is considered the first art school in the American continent and which in 1785, the year of its creation, was in the center of Mexico City. Different social, economic and political events led to the integration of this school into the University and years later, in 2013, the aforementioned postgraduate degree was created.

In 2019, after a bachelor's and master's degree in arts and in the innocent belief that the academic path was easy, I looked at my folio on the list of those accepted to the PAD's Doctorate in Arts and Design.

My approach to artistic research had been influenced, up to that moment, by authors such as Frayling (1993), Hannula, Suoranta and Vadén (2005), Hernández (2006), Borgdorff (2010), Arlander (2014) and Elkins (2014), although one of my main references has always been Natalia Calderón (2015).

In my first meeting with Y, he asked me to develop the basis of a graph that would later be transformed into a Complex Dynamic Schema (Serrano, 2017) and an Adaptive and Hyperbinding Information System or SIAH (Aguilar, 2018). These became the bases of many of my processes and the beginning of my permanent work with schemes.

My subsequent meeting with Y, A and J was disastrous. I felt destroyed. I must admit that I was not very prepared, but it helped me to notice that I needed to be clearer, confirming my affinity with schemes and their usefulness (Arellano & Santoyo, 2012; Novak, & Cañas, 2006).

Germinate

The tree of knowledge has functioned as a metaphor in various areas of human life, from religion to the life sciences. Linguistics, for example, has applied this metaphor to visualize relationships between natural languages. In biology, it is taken as a resource to graph phylogenetic trees that show the evolutionary history of a taxonomic group.

Its use certainly invites a thought that generates evolutionary and linear descriptions. However, I chose this metaphor because it is also possible to understand it in a different, more systemic, complex and human way.

An inevitable comparison is the concept of "rhizome", proposed by the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (1976), who use it to make an explicit and radical critique of the metaphor of the tree. These thinkers propose that the tree represents a hierarchical way of thinking with a vertical organization that follows linear and causal patterns. They also mention that each element is constituted with a fixed and stable identity and, finally, they refer to the exclusion of the multiple. All the above entails a limitation of creativity, divergent thinking and the connection between various elements.

I believe that, more than a confrontation, understanding the tree as an ecosystem and not as a static entity allows us to dialogue with the rhizome proposal, finding in it a complementary metaphor. The tree has structure, hierarchy and verticality, but these characteristics do not imply isolation. Rather than a contradiction, the tree represents a bridge between the individual and the collective, a starting point for understanding the ecology of relationships that exists in any complex system.

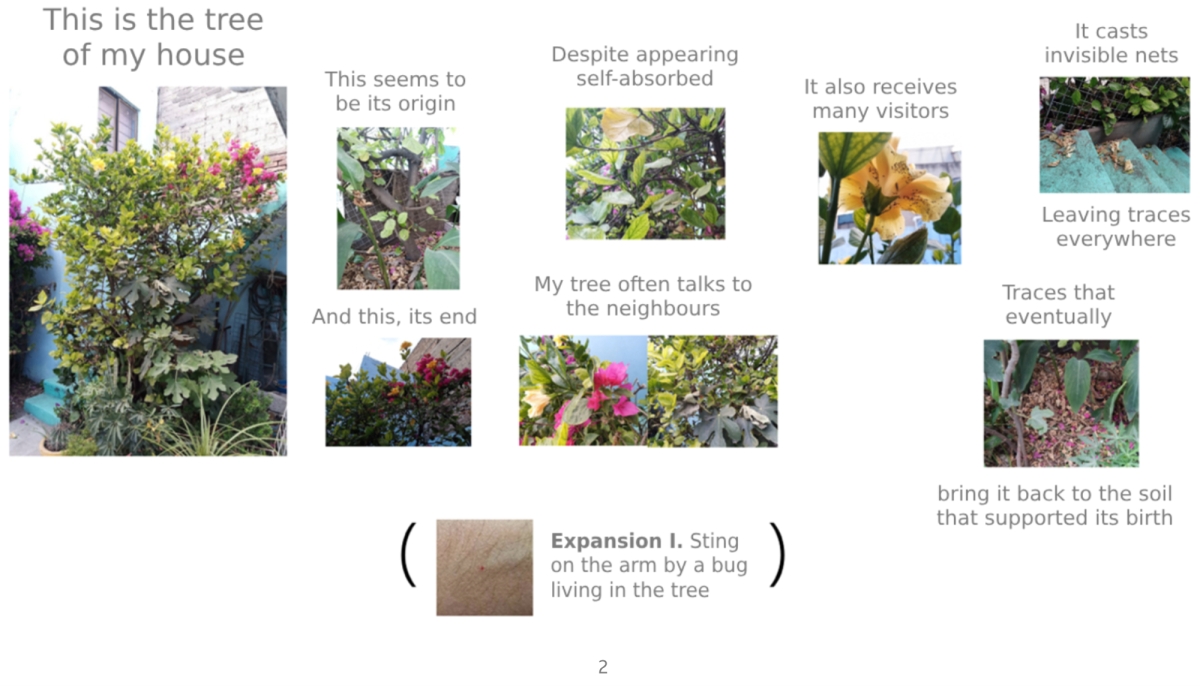

Sitting in the garden of my parents' house (the house north-east of the city, where I have spent most of my life), I found myself looking at the tree next to me. Perhaps because of my particular sensitivity, perhaps because of the reality of the encounter, I did not see a classification, a linearity or a hierarchy, I saw an ecosystem. The tree embodies the qualities of life and its growth. In it are the ideas of origin, substrate, root, development, flowering, pollination and more, in addition to the interactions between its cells and those of its symbionts, its interaction with the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, the soil, other macrofauna, such as squirrels, birds, but also insects, etc. The tree is not an isolated unit; it is a network of networks, a microcosm within a macrocosm. The tree includes the concept of rhizome, but by not limiting itself to that interaction, one can highlight not only the horizontal connections, but also the verticality and multi-scale relationships that are structured from it.

Therefore, I propose to consider the tree as an agent of an environment-context, rather than a differentiated unit, assuming the aforementioned ecosystem position.

The presentation of my research in the form of a tree makes explicit the historical substrate, the origins, processes and results. It emphasizes the direct connections that were generated, but also those emerging dynamics and even the unfinished paths. It is not possible to speak of a closure or conclusion, since their dynamics of interaction will have expanded the work to many other possible dimensions, people, contexts, disciplines or research.

I begin with a chronicle (Figure 2) and it is built in strategies that move from the visual to the material.

I thought that the review of European authors would be enough to cover my object of study: the doctorate. It was from Esche's proposal (cited in Slager, 2012) about an arts research academy without specializations, without isolations and without hierarchies that I realized that, clearly, these proposals did not operate in the context of my doctorate, which was characterized by having a disciplinary structure, specialization, isolation and hierarchy. In my perspective, UNAM in general has this tendency: far from being a space for the creation of free knowledge, it is a fierce battlefield, with impositions of power and inequalities in many ways.

Starting a little from scratch, but with a necessarily situated vision, I then set myself the task of establishing new theoretical and methodological lenses for my analysis, which would consist of the revision of the theses generated in the doctorate.

Thinking about a methodological diversity, in the manner of Paul Feyerabend (2010) taken up by Hannula, Suoranta and Vadén (2005), my crystals —a term I use to replace the idea of the theoretical framework due to its narrowness— were complex systems (Gershenson, 2011; 2013), the theory of social fields (Bourdieu, 1990) and sculptural practice. The latter, because I consider that the specific sensitivity with which we apprehend the world also shapes our way of investigating it.

I began, then, with the analysis of doctoral theses. To do this, I selected those that defined themselves as containing artistic practice as part of the work (excluding purely "theoretical" approaches). Being in confinement derived from the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, it was only possible to work with the theses available online, resulting in a corpus of 48 documents generated between 2013 and 2020.

The categories of analysis I used were taken from qualitative research proposals (Denzin & Lincoln, 2003; Guba & Lincoln, 2002; Morse, 2006; Vasilachis, 2006; Taylor & Bogdan, 2013). Due to my interest in unraveling the concept of "research-production", a conceptual axis that is proposed in the Graduate Program, I worked with a provisional analytical division between, on the one hand, the categories referring to the academic research process and, on the other, the elements inherent to artistic production. The result was as follows:

Academic practices:

a) Paradigms and theoretical perspectives

b) Research strategies

c) Collection and Analysis Methods

d) Interpreting and Presentation Practices

Artistic practices:

a) Artistic techniques/historical disciplines

b) Presentation Strategies and Resources

c) Theories and artistic positions

d) History of art (references)

I used the qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA, which allowed me to assign, count and visualize in an orderly way the categories that were assigned to each part of the documents, identifying not only the elements themselves, but the relationships between them, to carry out a further interpretation process.

Grow

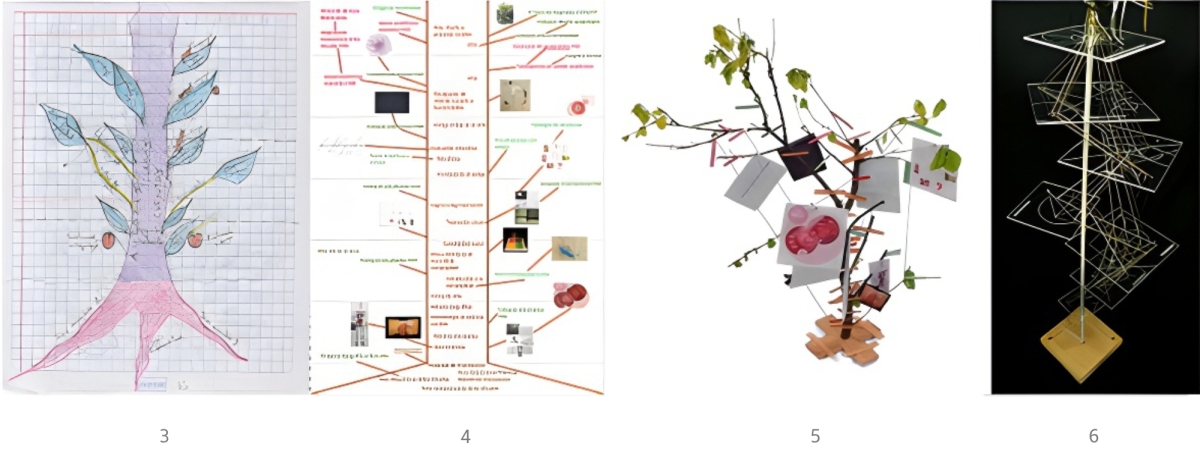

The first graphic allusion to the tree presents the trunk as the central theme of the research, the roots as its antecedents (mine), the branches and leaves as inquiries that were generated along the way, and the fruits as the results, socialized up to that moment (Figure 3).

Subsequently, we return to the schematization, alluding above all to the stratification and vertical branching of the tree. The elements that "entered" the central structure are presented in different colors, such as the formative events (seminars, workshops or classes), the artistic activities I attended, the management and teaching activities, the images resulting from that stage and the personal situations (Figure 4). At this point, a conception of research began to appear that overcomes dualistic notions such as theory-practice and focused instead on thinking about the different dimensions that we go through when researching, which, in addition, not only correspond to the usual academic or even artistic elements, but also to experience, dialogue, conversations, corporeality and a long etcetera.

It is also worth mentioning that all these elements probably do not correspond to the same semantic order. However, it is this dissemination of information in different strata, scales and dimensions that reaffirms the ecosystem notion. The tree of knowledge establishes connections with other trees understood as disciplinary borrowings, with other people, understood as dialogues and with other experiences.

These dimensions are linked in ways that are not always linear, establishing emergent relationships that become more evident in the first object stage of the tree. Working with a part of the original tree that was pruned, I integrated with texts and images the elements referred to in previous stages. I also placed threads of color that seek to make present in a material way the connections that appeared and that do not necessarily follow "natural" growth (Figure 5).

These connections represent the internal and external interactions that can occur during an inquiry. Such interactions are not visible or tangible, they are information. And that information is exchanged in different ways and in different languages and media.

The last personal work I made as part of the project was a sculptural piece that condenses the material and the formal in the presentation of the process. I placed transparent squares, like planes that rise in different axes. Each one is engraved with meaningful words, activities or sensations, as well as circular diagrams that refer to the first drawings I made. The planes are crossed by lines that generate different trajectories in space, creating an illusory volume (Figure 6). The closing word is ‘uncertainty’. We don’t know what will come next.

From the second semester of my doctoral stay, a diverse disciplinary and thematic interest exploded in me, probably motivated by my contradictory and impatient personality.

Although UNAM can be relentless at work, it is extremely generous with its students.

I attended the metaphysics seminar of the Faculty of Philosophy, courses on research methodology from the qualitative, the biographical, the autoethnographic, the grounded theory; I attended courses and seminars on complex systems, art and science, social complexity, art criticism, logic and argumentation, dissemination of the humanities and social sciences, educational evaluation and critical code in art. I also participated in the Permanent Seminar on Artistic Research SPIA coordinated by Dr. Natalia Calderón, and the Seminar on Art, Design and Social Processes coordinated by Dr. Yuri Aguilar Hernández.

I mention all this, not with the intention of making a curriculum summary, but rather to establish a position on the importance of dimensions that are not normally considered relevant in research. We tend to think of our referents as those great theoreticians; however, the construction of our thinking and therefore of our inquiry is also built from everyday experiences and interactions, disciplinary dialogues, feelings and experiences. The tree coexists with birds, ants, insects, but also with other trees, it is nourished by the water of the sky and the elements of the earth. Its paradigm is diversity.

Thanks to these formative experiences and the dialogues with C, S, J, R, R, A, N, Y, H and many others, the research took shape.

Beyond the results of the analysis of the theses, which can be reviewed more precisely in my doctoral thesis (Palacios 2023), the tree began to bloom. The main finding, without a doubt, was the proposal for classification regarding the relationship between academic practices and artistic practices, with which I came to the conclusion that graduate programs are not ready to have that conversation.

But that work, combined with the diversity of experiences, was only one dimension of the results. The central trunk of the tree generated numerous ramifications, seeking the objective of visualizing and socializing my processes. This was achieved through various strategies: the presentation of academic communications, the organization of events, the material elaboration of devices and the writing of various texts; although the most important so far has been the pedagogical possibility that detonated this proposal.

Bloom/Watch Bloom

Thinking of the tree as a strategy to visualize and socialize processes, I worked with my students on a similar initiative. The provocation was to think of ways to socialize their research processes beyond the traditional artistic exhibition or the academic article. My tree served as an example, but the richness of the matter was to co-construct sensitive paths that were combined with the nature of each project. This type of pedagogical exercise makes the research activity expand, makes sense beyond itself and its results. The tree in my house was always in the middle of an urban garden. That does not prevent it from dialoguing and socializing with other trees, and much better, with other environments, people and beings.

I am conflicted to operate under the label of "artist" or "researcher". Some years at the university have let me feel disenchanted with academia and its great figures. It's fortunate, since I can now conceive of myself beyond those rigid labels. For this reason, my person is constituted from my teaching practice, in the first place, and from the diverse reflections that derive from it, by specializing in the didactic-methodological issue of research in the arts. The activities of researching, teaching, learning, growing with others, seeing them flourish and take their paths, planting new trees of knowledge, have re-enchanted me.

The proposed exercise showed its fruits. First of all, I like to think that the research generated in my class carries some essence of the tree, which has expanded towards screen printing, the future, hegemonic images, feminism, dreams, art production, decolonization, verticality and all those themes and processes that R, J, N, A, E, E, D and N have worked on and that have found their own form of arborescence from sound, image, dance, installation...

Secondly, we were able to generate collective work. From a series of exercises and experiments, each one established a device to show their processes. The slogans were to get out of the traditional extremes of academic and artistic exhibition (the paper and the gallery) and think about what can be in the intermediate range, while allowing oneself to talk about the research process and not about the topics or results.

The result was a catalogue that develops each of the proposals, articulated from a joint title: "Mapping routes" (Figure 7). These devices will be exhibited soon.

The tree becomes a forest.

References

Aguilar Hernández, Y. A. (2018). Hagámoslo nosotros mismos: investigación inmersiva del arte en acción. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [PhD thesis, National Autonomous University of Mexico]. TESIUNAM Institutional Repository http://132.248.9.195/ptd2018/octubre/0781674/Index.html

Arellano, J., & Santoyo, M. (2012). Investigar con mapas conceptuales. Narcea.

Arlander, A. (2014). On methods on artistic research. In AR Yearbook. Swedish Research Council.

Borgdorff, H. (2010). El debate sobre la investigación en las artes. Cairon. Revista de Ciencias de La Danza, (13), 25-46.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). Sociología y cultura. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes.

Calderón García, N. (2015). Irrumpir lo artístico, perturbar lo pedagógico. La investigación artística como espacio social de producción de conocimiento. University of Barcelona.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1976) Rizoma. Pre-textos.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2003). Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Sage.

Elkins, J. (2014). Artists with PhDs: On the new Doctoral Degree in Studio Art. New Academia Publishing.

Feyerabend, P. (2010). Tratado contra el método. Tecnos.

Frayling, C. (1993). Research in art and design. Royal College of Art.

Gershenson, C. (2011). The Implication of Interactions for Science and Philosophy. Foundations of Science, 18(4).

Gershenson, C. (2013). Complexity. In B. Kaldis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Social Sciences. SAGE.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2002). Paradigmas en competencia en la investigación cualitativa. En C. Denman & J. A. Haro (Eds.), Antología de métodos cualitativos en la investigación social (pp. 113-145). El Colegio de Sonora.

Hannula, M., Suoranta, J., & Vadén, T. (2005). Artistic research-Theories, Methods and Practices. Academy of Fine Art and Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Hernández Hernández, F., Gómez Muntané, M. del C., & Pérez López, H. (2006). Bases para un debate sobre investigación artística. Ministry of Education and Science, Spain.

Morse, J. M. (2006). Asuntos críticos en los métodos de investigación cualitativa. University of Antioquia.

Novak, J.D. & Cañas, A.J. (2006). The Theory Underlying Concept Maps and How to Construct Them, Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01. Institute for Human and Machine Cognition.

Palacios Ruiz, I. (2023). Paradigmas y prácticas en contradicción. Acercamientos múltiples a los elementos que configuran las investigaciones doctorales en artes visuales del Posgrado en Artes y diseño y sus relaciones. [PhD thesis, National Autonomous University of Mexico]. TESIUNAM institutional repository. http://132.248.9.195/ptd2023/octubre/0848128/Index.html

Serrano Figueroa, L. E. (2017). Arte, diseño y complejidad ambiental urbana: recursos críticos del arte y el diseño en investigación acción interdisciplinaria sobre procesos culturales y socioambientales. [PhD thesis, National Autonomous University of Mexico]. TESIUNAM Institutional Repository http://132.248.9.195/ptd2017/septiembre/0765167/Index.html

Slager, H. (2012). The pleasure of research. Finnish Academy of Fine Arts.

Taylor, S., & Bogdan, R. (2013). Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación: la búsqueda de significados. Paidós.

Vasilachis de Gialdino, I. (2006). Estrategias de investigación cualitativa. Gedisa.

Biography

Itzel Palacios Ruiz. Born 33 years ago in the eastern part of Mexico City, she always dreamed of having a window overlooking the street. With a bachelor's degree, a master's degree, and a PhD in Arts and Design from UNAM, as well as a master's degree in education, she navigates between the academic and artistic fields, specializing in research methodology, artistic training, educational research, and complex systems. Of a conflicted and contradictory personality. She is currently a teacher and tutor in the Faculty and Graduate Program in Arts and Design, and although her window still doesn’t face the street, she remains hopeful.