With the COVID-19 pandemic and the rapid development of digital technology, the topic of digital identity and space have entered people’s daily lives. Telepresence has also become more dominant in work, education, society, and creative practice This reflective article discusses the use of telepresence for creative practitioners in the context of the pandemic. Rosina Yuan and Sherry Liu argue that tele-technology is an under-explored method for artistic exploration and collaboration; it can realize (inter)connection and interaction between people and manifests an alternative public space during a pandemic. Wilson Yeung and Jan Sze point out that telepresence can assist curatorial approaches, emphasizing the transition from ‘object-based’ to ‘people-oriented’ curation. The four researchers took the 2020-2021 student-led art project, Impro, as an opportunity to examine the online workshop model in the global pandemic.

RMIT University’s Curatorial Collective is an initiative led by art students. It was established in 2017 to promote collaboration between students and creative practitioners with different backgrounds. For many years, the Curatorial Collective has been committed to exploring diversified, innovative, and collaborative curatorial and creative methods.

Impro was initially planned as a series of face-to-face collaborative art workshops on the campus of RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. The project aimed to explore the concept of impromptu curation, to study the possibility of collaboration between contemporary art and exhibitions. Unfortunately, affected by the pandemic in 2020, art students lost physical contact and opportunities for creation at all levels. The profound impact of this special situation on creative activities prompted the Curatorial Collective to investigate the isolation and its influence on student artists, and the collective decided to move the entire project online.

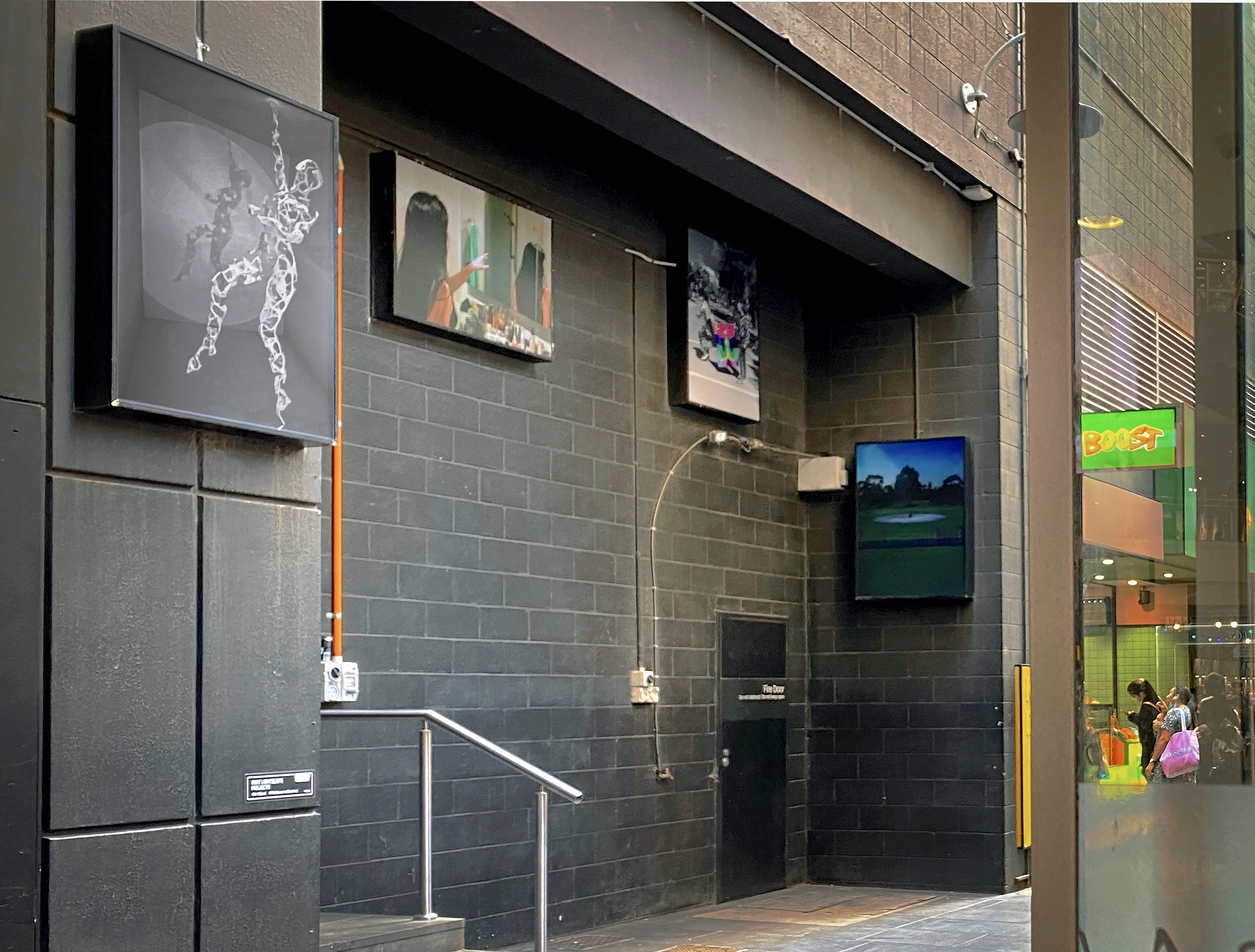

As an online-based collaborative art project, Impro connected the community and provided care during the COVID-19 while exploring dialogue and companionship. This experimental project involved various artistic activities, exploring the transformation of online and offline creation and display, and was overseen by two curatorial teams. Wilson and Jan curated the workshop We wandered in the wilderness (in April 2020). Rosina and Sherry developed the workshop In Companionship (in October 2020). Thirteen student artists created eleven lightbox works, which were planned to be exhibited at Rodda Lane and Knox Place-Melbourne Central. These student artists came from different cultural backgrounds and had various artistic practices, including printing, textiles, painting, photography, and digital media. Through the telepresence (inter)connection, we formed dialogues of production, development, presentation, and self-care.

In their work, Wilson and Jan engage with the dynamic relationship between curators, artists, artworks, and audiences. Rosina is a digital artist interested in digital ontology and telepresence. She brings new insights into how artists and practices occupy digital space, and how digital space influences artistic practices. Sherry is engaged in the art field of social participation. She investigates the digital space in artistic practice to promote public participation and interaction. During the development of the Impro project, the organisers intended to discuss how artists and curators can create together in physical space and digital space. How do people interact? How do creative practitioners encounter each other? Most importantly, where do the artists look for companionship during isolation?

Telepresence as (Inter)Connection Agency

The Internet has played a significant role in public and social participation. This has become especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the Internet has become more important for social communication and interaction. Zoom is a widely used online conference call application, and it has been used as a compensation and remedial measure for physical isolation. People can use Zoom to communicate in a group in real-time to break the barriers of distance. As a telepresence technology, Zoom provides another way for individuals to participate in collective activities and dialogues in isolation.

(Inter)connection is not an action but an experience. Although the Internet can build a bridge for connection and communication, experience is the essence of forming a ‘meaningful’ relationship and facilitates dialogues. Telepresence usually refers to technologies that allow remote operation and control, such as telephone, television, and telescope. They are a type of agency that allows people to access and control at distance. The word telepresence holds a certain oxymoronic overtone (Goldberg, 1998). ‘Tēle’ from Greek means at a distance, and ‘presence’ means something present that is visible or concrete in nature (Merriam-Webster, 2021). Although Zoom can only allow people to communicate and engage remotely, it presents perceptual information that corresponds to a remote physical reality (Goldberg, 1998).

In the context of COVID-19, most people have experienced isolation, and this shared physical perception creates the potential for ‘affective interaction’. ‘Affective interaction’ is a term coined by Sherry. Inspired by Gilles Deleuze’s affect(philosophy), Sherry believes that there is an implicit, dynamic process in which experience can stimulate interaction and resonance in the environment. Media theorist and educator Eric Kluitenberg (2015) indicated that these similar experiences can be contained in the capacity of resonance impulse from the environment. When people turn on their camera and see other people through the digital screens, they can understand each other's ‘affect’, feelings, and emotions because they seem to be in a group.

In the Impro project, the curators first considered what they could do to support each student artist and asked them about how they viewed the situation. They revealed that teleconferencing and video calls made them rely more on listening and dialogue. The curators, began to care more about the experience and feelings of the student artists at the time, than about the resultant artwork they wanted to create. The team strived to create a comfortable online environment and provide participants with a shared, friendly, and collaborative space to talk and communicate. This model of participation chose empathy-based care in difficult times. Student artists from different situations and cultural backgrounds could share everyday experiences and emotional resonance when they met and connected. Friendship among the student artists and the curatorial team was established from the ongoing online exchanges. They learned about the different needs of participants in their life and creative practices, and became familiar with the various impacts of the pandemic upon them.

For example, some student artists expressed they had been looking for an outdoor lightbox space to show and share their thoughts and emotions about isolation; others shared the hardship of living alone and the anxieties of seeking self-accompaniment. The online workshops involved dialogues, encouraging participants to share their stories and make connections. Gradually, the curators became both emotional experiencers and collaborators in student artists’ creations, exploring how art practice can involve accompanying each other in this challenging era. In the process, according to the improvisational nature of the project, the boundary between curator and artist became blurred.

Application of Telepresence in Artistic Participation

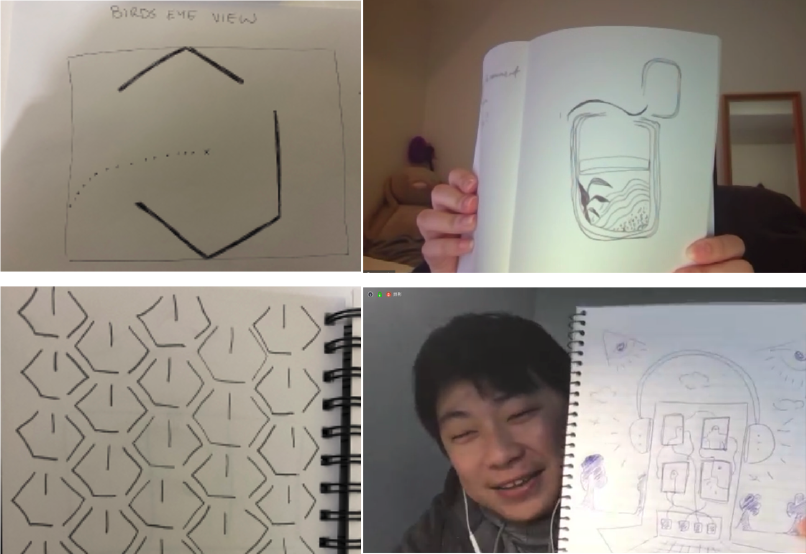

The co-curators found that student artists had varied experience and skills in digital technology, however, as young creatives, participants were willing to use digital tools in workshops and in their practice. Student artists introduced various online activities and games as interactive art, sharing their daily concerns in the workshop. These activities seldom paid attention to art forms and creative achievements, preferring a focus on communication, exchange, and negotiation. This attitude was reflected when student artists let go of their usual practice or techniques and adopted a more direct interaction and communication method.

In one of the activities, student artists drew sketches to show their living environments; some pictures were figurative and symbolic, while others illustrated their feelings. The exercises lead participants to think about the things they were grateful for from the past to the present and the discussions enabled participants to express their ideas humorously and comprehensively. When each student artist held and showed their sketch in front of the camera, the gallery view in Zoom made it seems like a new artwork that summarized collective and social memories of the global pandemic. By participating in these activities, the distinct roles of artists and curators were transformed into artistic collaborators. They do not encode messages unidirectionally, but made an open-ended expression and context in this dynamic environment (Kac, 1993).

In these workshops, telepresence provided a pragmatic and operational medium that created intuitive interfaces, links, and connections for art (Kac, 1993). No physical media were used; instead, the creative and interactive process used the Internet and digital means. Rosina emphasized that screen-sharing and recordings allows participants to experience virtual exhibitions and digital artworks in real-time; they can travel the world virtually and discuss the future of gallery spaces and art archives. The telepresence employed in art introduces the notion of expanding space as a bridge to another place (Kac, 1993). When each student artist converts their work into digital formats, they need to explore and use the digital screen as a metaphor for their perception.

Rethinking Presence and Public Space Shaped by the Internet

Writing about the potential of telepresence in engineering and how it might influence the future economy, American cognitive and computer scientist Marvin Lee Minsky wrote, “To create true telepresence, we must supply more natural sensory channels…” (1980) Diverse types of tele-technologies offer different interfaces and ways of telepresence, and the effectiveness of the technology does not rely on total immersion with expansive sensory channels, but depends on how it has been used. Reflecting on audio-visual communication in Impro, the researchers argued that companionships manifested through digital screens are authentic and effective. It may be seen as a compromised alternative solution to the physical presence during isolation. However, the unique attribute of distance is also a more inclusive advantage and allows people to focus on verbal communication.

References to transmission, isolation, and social distance have dominated the media throughout the pandemic period, and this has aroused people's interest in public health. Naturally, people have started to rethink their physical states and change the level of their concern about health threats. Some artists became more concerned about where they go, what they do, who they talk to, and even what they touch. This phenomenon may have a lasting impact on how people view their bodies and the nature of socialization.

Tele-technologies expand the way people perceive and exist, allowing people to live in multiple ‘locations’ simultaneously. The video and digital imagery capturing an event are undoubtedly different from the thing itself. They are properties transmitted through the Internet and mediated through screens (Paulsen 2017, p. 9). Nonetheless, we can easily accept them as valid realities – though we are not in the same space, the presence of others is vital. Participation is possible because of the distributed and connected nature of the Internet. In art projects during the pandemic, telepresence was used to convey interactive visions to the public. For the student artists involving in the Impro project, digitization became a precondition for all submitted artworks, they were asked to adopt specific digital formats for the works to be printed and exhibited in lightboxes. Hence, digital editing was an essential part of the process. Student artists could use these editing tools to give each other feedback and effectively provide visual concepts and references.

In the final online workshops, student artists, isolated in different spaces, achieved a common visual experience using video, sound, or multi-media. A curator and filmmaker Pauline Drescher proposed, “Presence here is conscious, especially because the spectator needs to perceive two different environments simultaneously: the psychical environment and the represented mediated surrounding.” (2009, p. 8) This was the case in the workshop, where perceptions were based on dialogues and mutual understanding, and passive participation was essentially forced by the media. This was different from conventional face-to-face workshops where the presence of others and the artworks were unquestionable.

The Impro project aimed to establish dialogues and ‘take care’ rather than make conclusive statements about emotional experiences. Despite the lockdown, we still insisted on delivering these artworks to the physical space. This delivery required a digitization process for printing, but they were juxtaposed within a complex biological environment. The presence of these lightboxes made the materiality and boundary between media ambiguous. Lightboxes became windows to the public space. Each window led to the artist’s manifestation, expressing their feelings and voices about living in the pandemic.

When the digital photographs were exhibited on a shared screen through Zoom, the screen effectively removed a sense of context and environment from the works; displayed as an online exhibition, the possibility of dialogue and open communication with and around the photographs seemed reduced. In comparison, showing the works on the facade of a building, placed the art in an unstable state, where works of art to be given another identity when they were encountered by different people, producing unique interpretations. The pandemic has become the experience, knowledge, and memory of the global collective. When the artworks were encountered, together, in physical space, they could provide more opportunities for empathy and resonance, and encourage more diverse dialogues.

Ongoing Dialogues

This article is a collective reflection on the Impro project. It summarizes the unique artistic approach, delivery, and social setting of the project, which contributed to the individual developments of participants and curatorial dialogues of practicing care. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Curatorial Collective used tele-technology to interact with the student artist community and the public. By planning online and offline art activities, they re-examined the role and function of art curating and found that curating can entail being keenly aware of the needs of artists and society, by exploring new ways of encountering, collaborating, and forming dialogues. The devastating impact of the pandemic is shared by numerous people, which lays the foundation of mutual understanding. The initiators of the Impro project hope to re-establish community dialogue in both physical and digital spaces in future artistic practices.

References

Minsky, M. (1980). ‘Telepresence’ in OMNI. Jun.

Paulsen, K. (2017). Here/There: Telepresence, Touch, and Art at the Interface. MIT Press: Cambridge.

Goldberg, K. (1998). ‘Virtual Reality in the Age of Telepresence’ in Convergence, The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 4(1), pp. 33-37.

Anon. (2021). Presence. In: Merriam-Webster. [online] Available at: <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/presence> [Accessed 20 Mar. 2021].

Kac, E. (1993), ‘Telepresence art’ in Teleskulptur 3. Kulturdata and Division of Cultural Affairs of the City of Graz, Graz: Austria. pp. 48-72.

Drescher, P. (2009), Understanding Telepresence in Art and Society. Universiteit van Amsterdam: Netherlands.

Kluitenberg, E. (2015). ‘Affect space: Witnessing the movement (s) of the squares’ available at: <https://onlineopen.org/download.php?id=298> [Accessed 20 May. 2021]

Biographies

Chun Wai (Wilson) Yeung is an artist-curator, researcher, and creative producer. Wilson is currently a PhD candidate at the School of Architecture and Urban Design and an industry member of Contemporary Art, Society and Transformation (CAST) Research Group at RMIT University. Wilson is the founder of the Curatorial Collective in Melbourne, Australia.

Rosina Yuan is a painter, researcher, and digital designer. Rosina studied Fine Arts at the RMIT University and is currently researching virtual environments as a PhD student at the School of Architecture and Urban Design at RMIT University.

Wing Ting (Jan) Sze recently graduated from the Master’s in Arts and Cultural Management of the University of Melbourne. Jan also holds a Master’s in Arts (Arts Management) from RMIT University. She was the Vice-Chair of the Curatorial Collective in 2020.

Ye (Sherry) Liu is currently a PhD candidate at the School of Art, RMIT. Sherry’s artistic practice connects issues of the environment with social engagement to explore how creative practice illuminates the value of communities and creates emotional engagement with the public.