1. A wounded organism

Dependence isn´t only the plundering of resources.

Its ultimate purpose is the induction of meaning in the production of knowledge

and the place from where this meaning is thought.1

Every body of knowledge has its origins in the bodies-territory and territories-body that give it life. The creation and construction of knowledge, which is sometimes slow and processual and sometimes vertiginous and urgent, results from the composition of bodies, experiences, and soils. The same soil gives rise to diverse interpretations, meanings, and symbolizations by different human and non-human groups. This diversity is of special interest as evidence of interculturality (not monoculture), and pluriversity (not universality). Of interest as well is the powerful feedback provoked by the notion of body-territory/territory-body from decolonizing, ecofeminist, spatial, and environmental justice perspectives.2 What ways of knowing and investigating the world are possible within processes of extermination, cruelty, and plundering of territories and living beings? What qualities are desirable for the artist-researcher's subjectivity in communities and lands that have been violated and sacrificed? How do we imagine their tools and methodologies?

The present text aims to share reflections and concerns that will help bring the reader, who is an artist-researcher, closer to the Argentine context. It also establishes links between this context and the global context, which I propose to characterize as a ‘common world’: a post-pandemic, planetary commons in an eco-social emergency. These conditions and events result from the hegemony of a way of perceiving, conceiving, and imagining the relationship between nature and culture. This is an inheritance of Western modernity and its anthropocentric, logocentric, and phallocentric ontology and epistemology. This is evident in the emphasis placed on a dominant economic and social model linked to the belief in unlimited progress and the exploitation of ‘natural resources’ and human beings, as well as the consequent logic of wealth accumulation and concentration. It´s crucial to promote mutual listening, conversation, and exercises in political imagination among artist-researchers interested in creating a different common world than the exclusionary one that emerges from that heritage.

These objectives are consistent with the previous publication in the JAR Network Section of A constellated field (Molinari, 2023)3, a paper reflecting on situated processes of artistic research. It´s derived from my experience participating in the conception and development of the Artistic Research Grants, which were convened by the Secretariat of Heritage of the Ministry of Culture of the Nation, together with the Ballena Project4 of the Kirchner Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, Argentina, between 2021 and 2023. While still under the social isolation imposed by the covid-19 pandemic, the call was addressed to inter-, multi-, and transdisciplinary artists and centered on the neologism ‘T/tierra.’5 (E/earth). Written with two ‘t’s, the word draws attention to two scales: 1) Investigate the global and local effects of human actions on the environment and all living things. 2) Focus on contemporary modes of land access, ownership, and use. In the first stage of the call for artistic research grants, I was part of the selection jury. Then, I served as a tutor, supporting the development of the selected projects. Finally, I co-edited the book that compiled images, testimonies, and reflections produced by the scholarship recipients from various Argentine regions: Misiones; Entre Ríos; the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires; the Province of Buenos Aires (José León Suárez, Bahía Blanca, and Mar del Plata); Chaco; and the ancestral territories of the Mapuche people in the current Patagonia (Chubut Province). These territories are also the setting for the migratory drift of different native seeds.

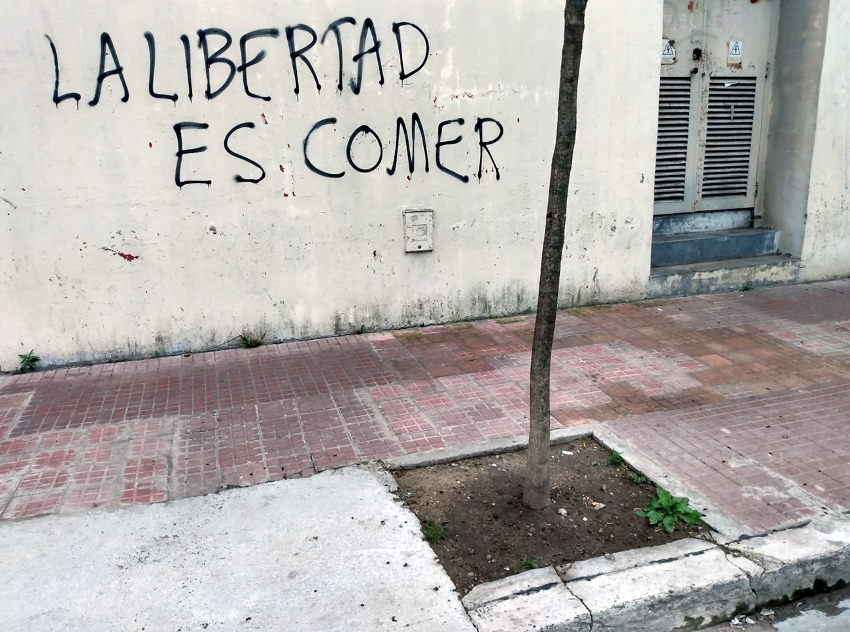

Thinking about artistic research means conceiving of an interdependent field of living forces that inhabit different corporealities. First, the bodies of the researchers as territory. Second, territories as body, spatialities that are never ‘empty.’ Third, bodies of living knowledge, which are the fruit of situated experiences and are embodied in different types of artifacts, devices, interventions, and actions. Artistic research implies processes of co-learning and co-teaching. It detects and/or creates knowledge. It can house, treasure, and transport knowledge. It can circulate and share knowledge or encrypt and protect it in secret. We´re always speaking of living, mutant knowledge that must be nurtured, cultivated, and cared for. As Calderón, Cervantes, and Salazar explain, it´s "mobile, unstable, and undisciplined knowledge that cannot be quantified as objects or data and that resists the accumulative logic of capital." (2022) At this point, it is important to note that if all artistic practices produce some form of textuality, then there is no text without context. This statement is relevant because it links both terms without defining them univocally. Each artist researcher must define these terms, which may result in rational, logical, and conceptual narratives or scientific discourses. Alternatively, they may follow the paths of unreason: sensory, emotional, and fictional narratives; hallucinogenic and delirious narratives. They will allow themselves to be affected and trapped by uncomfortable and divergent realities that unleash a methodological lack of control. The relevance lies in how each artistic research defines its own context or situation—the composition in which questions of interest appear. Each context possesses a certain historicity: a spectral handful of memories and legacies; ancestors, ghosts, and entities; collective voices; unfulfilled desires and latent dreams. Returning to our initial statement, we can conclude that behind every body of living knowledge, there are living bodies—the territories of researchers—and a living body-territory that is always inhabited by other beings and situated. We can conceive of these vitalities as part of a single living organism; an ecosystem. How, then, can we describe this organism through artistic research experiences in Argentina? A first sensory tour reveals that it is a wounded organism-ecosystem whose skin or bark bears the marks of its colonial history. These traces, scars, and open wounds can be seen in its geography and social body. These traces can also be seen in its precarious industrial, military, transportation, food, education, health, and justice infrastructures. These traces are also evident in its architecture and urban planning, and in the ruins of all of the above. As we circulate through these physical spaces, we will encounter powerful flows and forces. There are degenerative energies that evidence the presence of oppressive power. However, regenerative energies of pure life, resistance, struggle, liberation, and emancipation persist. These are the flows and forces that (neo)colonialism pretends are dead and buried, but which persist. Our artistic research seeks them out.

2. A handshake

First, we will kill all the subversives.

Then, we will kill their collaborators and sympathizers.

Then, we will kill those who remain indifferent.

Finally, we will kill the timid ones.6

The pedagogies of cruelty are daily in charge of teaching us

“not to feel, not to recognize our own or others' pain (...)

The world of owners we inhabit needs non-empathic personalities,

subjects incapable of experiencing the commutability of positions,

of putting themselves in the other´s place.7

Them, the enemy; they are an impurity, a toxin, a poison that endangers us. Only by degrading living organisms can we generate the conditions for their annihilation. While I don't want to bore the reader with a historical review, it does seem pertinent to present a hypothetical epistemological key to understanding and contextualizing the wounded organism-ecosystem mentioned above. This key proposes the continuity of a violent social drive, evident throughout Argentine history in the creation of an internal enemy and the subsequent need for its immediate annihilation or extermination. This ‘way of knowing’ the surrounding world, shaped by drive, conception, and strategy, continues to shape a pedagogy and a science. This drive, incapable of putting itself in the place of the other, shapes social insensitivity and influences how we perceive, conceive, and inhabit otherness; our links with nature; and the forms of participation and decision-making that seek political transformation in democracy.

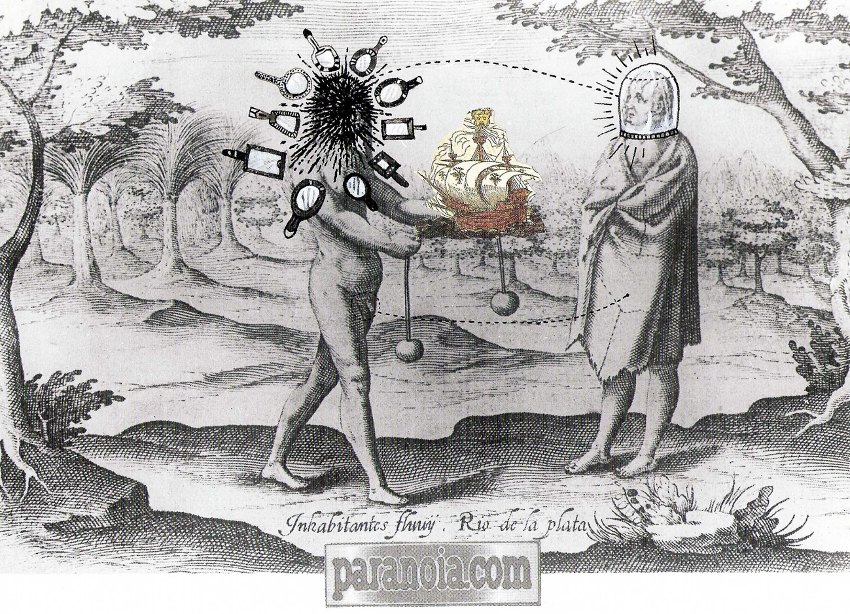

Some of the geography that makes up modern-day Argentina was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Created by the Spanish crown in 1776, the Viceroyalty's capital was Buenos Aires. The conquistadors' presence in the region is linked to the founding of Buenos Aires. Pedro de Mendoza founded the first settlement in 1536, guided by stories of ‘mountains of silver’ in the area. However, the fort and houses were soon abandoned due to hunger and harassment by the Querandí natives. Juan de Garay definitively founded the city in 1580. The introduction of horses and cattle by the Spaniards changed the region forever. The rapid reproduction of cattle ensured a food supply and gave rise to a significant business: the export of hides and meat, a practice that continues to this day. The increased use of horses gave a sense of identity and empowerment to those who acquired horsemanship skills. Indians, gauchos, and slaves brought from Africa were central figures in the social and cultural structure of this territory, embodying a way of life linked to the pursuit of greater freedom of movement in a borderless space. On the other hand, for the city-port's privileged social sectors, which were linked to the colonial authorities through political and commercial interests (including the legal and illegal export and import of goods), the ‘inland’ and its inhabitants posed a real threat. Perceiving themselves as ‘decent people,’ they maintained an alienated relationship with the land itself and the original inhabitants and popular sectors.

In 1806, during the Napoleonic wars in Europe, the United Kingdom attempted to invade Buenos Aires to control the estuary and the main access to the continent. The invasion was repulsed, as was a second attempt in 1807. The stories I learned in school included intense sensory details and information about the skin color (more or less black or brown) of the local armies. They also described the devastating effects of boiling water thrown by neighbors from the terraces of their houses on the invaders' bodies. Although the British colonialist pretensions were frustrated, it would not take long for them to take their revenge by forcefully occupying the Malvinas Islands in 1833. This distant archipelago in the South Atlantic has a sparse and inactive population but strong roots in our history. The Spanish authorities were officially deposed in 1810 and replaced by a Provisional Government Junta, which sparked wars for independence that spread throughout the South American region. The armies, which were largely composed of mestizos, gauchos, blacks, and Indians, confronted those sent by the King and Queen of Spain. Argentina declared independence in 1816, though the struggle for different models of government intensified in the interior of the country. The Buenos Aires merchants' alliance with the Pampean landowners and their representatives in the interior provinces tried to impose a unitary, centralist government. Meanwhile, popular sectors organized through local leaders (‘caudillos’) advocated a confederation. The civil wars culminated in 1852 with the triumph of the centralists and the promulgation of the first National Constitution in 1853.

For readers interested in artistic research in the Argentine context, it´s important to approach the philosophical, political, and aesthetic categories that influence the narratives and imaginaries that cross our ways of experiencing and knowing the world, of investigating it and creating knowledge. The antagonistic slogan "Civilization or Barbarism"8 encapsulates that internal conflict, which originated under the influence of scientistic positivism but is still prevalent, even in the violent speeches of our current president. Historical supporters pointed out two evils to combat: 1) The excessive territorial extension of the country. Paradoxically, they designated vast territories as ‘deserts’ even though they were inhabited by native peoples. 2) The negative qualities of the native population. It took them a long time to recognize indigenous peoples, blacks, and gauchos as fully human. They considered them barbarians, savages, and lazy but apt to be transformed into slaves, servants, and soldiers. From 1870 onwards, there was a shift in this narrative due to Argentina's insertion in international markets and the sale of raw materials to industrialized nations. From 1878 to 1885, the military campaigns known as the ‘Conquest of the Desert’ were carried out under the leadership of Julio A. Roca. The armed forces committed genocide against the indigenous populations of the Pampa and Patagonia regions. This included the forced disciplining of the gauchos, who were subjected to proletarianization, which was essential for the agro-export model. This ‘conquest’ is considered the founding genocide of the nation-state. The oligarchy believed that they could complete the annihilation of ‘barbarism’ through immigration policies, but these policies soon showed their political reverse side. Instead of the desired Anglo-Saxon immigrants, workers arrived from Spain, Italy, Russia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. At the beginning of the 20th century, these politicized subjects became the protagonists of the first workers' and trade union struggles. The dichotomy of civilization versus barbarism has shaped political, historiographic, scientific, literary, and visual narratives and imaginaries, and continues to do so today. This includes pedagogy, research, and knowledge production. It has shaped a specific mode of political dispute and violence between two factions without a third protagonist. This dispute and violence continued into the 21st century, pitting a minority subordinated by its own conviction- to successive international divisions of labor and forms of cultural domination (first European, then North American), against popular majorities that are postponed and excluded. These majorities led important struggles and gave rise to the main political parties and movements (radicalism, Peronism, the Marxist left, and progressivism), which turned their inclusion in democratic life, the validity of their social and labor rights, and the free development of their own culture into reality.

It´s important to note that Argentina has a long tradition of artists who are committed to blurring the boundaries between art and politics. Among the experiences that have influenced my generation of research artists the most are those involving significant interactions between social actors engaged in struggles and resistance and individual artists or artist collectives. These interactions produced intense processes of aesthetic experimentation, crossing artistic languages, as well as rich works of detection, creation, and transmission of living knowledge, information, memories, and imaginations. These works sought to influence different political, social, and cultural situations, strengthening the forces of transformation.

One example from the beginning of the 20th century is the Artistas de Pueblo (José Arato, Adolfo Bellocq, Guillermo Facio Hebequer, Agustín Riganelli, Abraham Vigo), who nourished themselves from the social context in which the prevailing oligarchic regime disputed the sanctioning of laws that would allow popular majorities to participate in democratic elections. They also built new contexts from their critical relationship with official art institutions. This includes the creation of the ‘Salón de Recusados’ and their connections with cooperatives that supplied materials for artistic creation and production. We are also talking about their choice of engravings and publications as tools to spread their ideas and imagination more widely. Another example is the use of trucks and the realization of exhibitions in streets, unions, and at the exits of factories to strengthen ties with the working class. Between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, these territorial links with the popular and community worlds were also present among another group of artists: the Painters of La Boca. This group included Juan Del Prete, Alfredo Guttero, Víctor Cúnsolo, Miguel Diomede, Alfredo Lazzari, Fortunato Lacámera, Benito Quinquela Martín, and Raquel Forner, among others. They paid special attention to capturing neighborhood and port-life sensitively, and to community forms of organization in the urban margins. I see a common trait among these two groups of artists: their desire to inhabit specific sites of proletarian, migrant, and marginal life with their art, as well as their confidence in the transformative power of artistic practices on reality. This trait is similar to that of some singular artists or new groups of artists from the 1960s and 1970s, as well as those that emerged at the beginning of the 21st century around the 2001 crisis in Argentina. These were all moments of greater closeness and proximity between artists, community life, territory, and counter-hegemonic struggles.

I find a common thread here that accounts for the fusion of art, life, and politics. This thread weaves a persistent presence of the human figure in the works of artists such as Antonio Berni, Aida Carballo, Carlos Alonso, Jorge de la Vega, and Marcia Schwartz. These artists found various ways to make the excluded visible, whether they were ignored or persecuted. This thread also connects with the plot of situated experimentation and collective artistic research in convergence with the social sciences. This thread is also seen in various actions of defiance against the prevailing regime of visibility during the period of Peronist proscription and military coups. Among others, I am referring to Alberto Greco's remarks (his Vivo-Ditos in the early 1960s), the actions and research of the Tucumán Arde group (1968), Carlos Ginzburg's actions and interventions (early 1970s), Victor Grippo's oven in a public square (1972), and the intensity provoked by the narratives and imaginaries of artists such as León Ferrari, Juan Carlos Romero, Edgardo Vigo, and Luis Pazos. I see a common interest in experimental research that seeks to unveil knowledge, information, or sensibilities buried, silenced, or annihilated by authoritarian and anti-democratic forces of the time. These investigations are more or less plastic, artistic, sensorial, and material, but they also bear disruptive and challenging poetic and political forces. These flows led many artists from different disciplines to put their artistic work on hold or space it out in order to fully commit to the political struggle, even to the point of losing their lives. I´m thinking of Franco Venturi, a visual artist. I´m also thinking of Héctor Oesterheld, scriptwriter and the co-creator of the popular comic strip El Eternauta with cartoonist Francisco Solano López. I´m also thinking of Raymundo Gleyzer, a filmmaker and director of incisive documentaries. And Rodolfo Walsh, a writer, whose journalistic and literary investigations pioneered what we know today as nonfiction.

As part of a generational experience shared since the return of democracy in Argentina, I´m interested in highlighting the ‘Siluetazo’9 a collective and collaborative action by the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, artists Rodolfo Aguerreberry, Guillermo Kexel, and Julio Flores, and attendees of the Third March of Resistance. This event took place in Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires between September 21 and 22, 1983. In an open workshop, participants laid their bodies on paper and had their silhouettes drawn. Then, they pasted those drawings vertically on the surrounding buildings. This attempt to evoke and make present the absent due to dictatorial violence was also an emblematic case of questioning the concept of artistic authorship. What interests me most about this experience, however, is how it contributed to a social and collective journey—both artistic and extra-artistic—to find research tools and methodologies that allow access to the truth. In this case, the truth about what happened to citizens who disappeared during the last Argentine military dictatorship. If all research puts at the center, in different ways, questions about the truth of what is investigated, ‘Siluetazo’—whose blurring of the boundaries between art and politics, which includes a reconfiguration of the concept of authorship—opens the possibility of rethinking the body-territory / territory-body relationship. I will return to this point later. Within the framework of this legacy, it´s important for me to mention two collectives with which I have shared art-life since the mid-1990s: the Grupo de Arte Callejero (GAC)10 and the Etcétera group11. Together with human rights organizations, both have always embodied modes of artistic experimentation and research in the struggles for memory, truth, and justice.

Argentina experienced six dictatorships in the 20th century12, with coups d'état executed by the armed forces, with the involvement of civilians and sometimes of the catholic church. The last military dictatorship (1976-1983) implied a radical change in the use of institutional violence, giving rise to a phenomenon that reached an unusual systematicity and scale. I am talking about state terrorism, a clandestine method of persecution, kidnapping, imprisonment, torture, murder, concealment and disappearance of the bodies of the victims, all those who were labeled by the repressors as ‘subversives’. It included the theft of babies and the removal of their identities. The armed and security forces, under the orders of the Military Juntas and their National Security Doctrine, were trained by French military (counterinsurgency methods used in Algeria) and American military (teachings of the School of the Americas). The most traumatic effect of this exterminating action was the disappearance of 30,000 people in Argentina. The figure simultaneously illustrates the magnitude of the crimes committed and the difficulty of determining an exact number of victims, precisely because of the clandestine nature of the events and the pact of silence among the perpetrators. These actions are considered genocide and crimes against humanity, and are therefore imprescriptible. The objective of this violence was to initiate a ‘process of national reorganization’ and transform the economic, social, and cultural structures at their core. In 1979, those responsible for these crimes honored and vindicated the work of their military colleagues during the ‘Conquest of the Desert’ at the end of the 19th century. The ‘anarcho-libertarian’ alliance currently governing Argentina, chainsaw in hand, does not cease to publicly vindicate both experiences.

Since then, the Argentine organism-ecosystem has had to coexist with the effects of this true "biopolitical machinery for the production of spectra" (Pérez, 2022). The violent transformation marked by blood and fire has influenced successive governments since the return to democracy in 1983. The seeds of the neoliberal experiments that began in 1989 were planted in that violent mark. The governments of the 1990s were responsible, along with international lending agencies (specifically the IMF), for leading the country into the 2001 crisis. The day after the twentieth anniversary of the last military coup, March 25, 1996, Secretary of Agriculture, Fishing, and Food Felipe Solá of Carlos Saúl Menem's government, signed Resolution 167, which authorized the experimentation, production, and commercialization of ‘glyphosate-tolerant soybeans’ and their derivatives in the country. Thus, Monsanto's transgenic RR soybeans entered the country, initiating the process known as ‘sojización.’ After the United States and Brazil, Argentina has more than 40 million hectares of crops. GM soybeans alone occupy nearly 19 million hectares for the 2024/25 sowing season. Although there are no official statistics, it is estimated that more than 300 million liters of pesticides are sprayed on these lands every year. Argentina ranks first in the world for pesticide use: 10 liters per person per year13. The environmental, health, social, and cultural consequences of this ecotoxicological experiment are closely linked to the tools and methodologies used, such as direct sowing, pesticide use, fumigation, and land clearing. These tools and methodologies have lethal effects, including floods, droughts, fires, land, air, and water pollution, population displacement, cancer, infertility, and birth defects. The agribusiness model implies the extermination of all unarmed living beings that do not resist agrotoxins. The neo-extractivist machinery also includes sacrifice zones for the development of mega-mining and lithium exploitation. Real estate business, wild urbanism, financial speculation and institutional racism emerged around these areas. The Indigenous Women and Diversities Movement14 defines this necropolitical process as ‘terricide’, a word that synthesizes a simultaneous annihilating action: ecocide, genocide, feminicide and epistemicide.

The wounded organism makes an awkward and absurd gesture. It manages to shake its own hands. Genocidal thought and terricidal action shake hands. A liquid makes the contact uncomfortable. They are bloodstained hands. What can we learn from this gesture? Can we investigate artistically to the point of breaking the impunity, the regime of (in)visibility, and the silence imposed by genocides and terricides? What knowledge will we find there? The Whale Project's Artistic Research Grants undoubtedly delved into the causes and effects of this situation.

3. A mutilated body

I love to be the mole that destroys the State from within.15

Argentina's period of neoliberal hegemony (1989-2001) culminated in a profound economic, social, and political crisis in December 2001. This crisis occurred shortly after the attacks on the Twin Towers and the subsequent declaration of a ‘war on terrorism’ in the United States. A popular revolt ousted the government, raising intense questions about the meaning of ‘work’ when the state and capital abandon the people. It also raised questions about desired forms of institutionality and decision-making in democracy. In relation to the previous analyses, the governments of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner sustained and renewed their commitment to the social consensus established in 1983: ‘Never again’ to the crimes committed by the last military dictatorship. Encouraged and accompanied by the historical struggles of human rights organizations, the state took responsibility and promoted memory, truth, and justice policies that included trials and the effective imprisonment of genocidal perpetrators. The case of former dictator Jorge Rafael Videla, who died in prison, acquired very high symbolic power. In line with the regional geopolitical situation, during this period the state acknowledged its place in Latin American history and confronted the challenges of greater regional integration. Although Argentina's progressive governments achieved significant social inclusion and believed in the positive effects of wealth redistribution and increased domestic consumption as economic drivers, they did not make substantial changes to the country's economic structure. Although the ‘commodity consensus’16 provided macro-political support, neoliberalism transformed sensitivity into a micro-political battlefield. Fake news, judicial harassment, and hate speech added to the subjective and collective difficulty of imagining and producing changes in ways of life and consumption, which were increasingly subject to labor flexibility and precariousness. Pedagogies of cruelty did their thing. The chosen metaphor for this new version of the old necropolitical narrative aligned with the spatial turn of the crisis of global capitalism and its associated ecological crisis. Argentina is divided in the 21st century by a crack. The organism (bodies-territory + territory-body) is broken. “Democracy is a mixture of the warfare state, which makes politics a permanent search for enemies to eliminate, and postmodern fascism, which reduces freedom to personal opinions and admits difference only if it´s claudicating.” (López Petit, 2014). The governments of Mauricio Macri (2015-2019) and Alberto Fernández (2019-2023) show different ways to claudication. Macri's administration was characterized by a frustrated attempt to return to the 1990s, while Fernández's administration was marked by manifest ineptitude and an inability to effectively support the most vulnerable. Macri requested the largest loan ever granted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), ignoring the institution's own internal regulations. Fernandez's future was marked by the questioned management of the Covid-19 pandemic, forced renegotiations with the IMF, and a vertiginous increase in inflation in 2023. Amidst growing discursive violence against Kirchnerism, dolls with the faces of the leaders, guillotines, mortuary bags, and lit torches against the government house were part of a dangerous repertoire of ‘performances.’ On September 1, 2022, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was the target of an assassination attempt in front of her home. The attacker sought to fire two shots at her, but the gun failed to fire. Despite the expressions of condemnation from different sectors of society, no popular crowd expressed a sufficiently overwhelming reaction. In the post-truth era, frustrations arose, caused by the failure of the last two governing alliances (simultaneously representing the opposite poles of ‘the crack’ and the ‘political caste’) to fulfill their promises to improve the quality of life for Argentines. These frustrations combined with the hate speech against ‘left-wing populism’, the anti-political mood stimulated since the pandemic years, and the uncertainty about the future of a planet showing more and more signs of climate distress. Together these factors worked during the 2023 presidential election process as a device of social, political, economic, and cultural atomization. The concentrated powers that be organized around this malaise and soon found the best person to interpret it: Javier Milei. They legitimized the emergence of a figure outside the traditional parties who could embody the transition of neoliberalism from cynicism to hatred and from there to cruelty. Without any modesty, he recreated a narrative based on eliminating the enemy: social justice.

From the outset of my text, I propose that "behind every body of knowledge, there are bodies-territory and territories-body" and ask what the desirable and possible ways are of knowing and investigating the world within processes of plundering and the unlimited extermination of biodiverse life. Perhaps the main symbol chosen by the current ruling libertarian worldview—the chainsaw—shows the extremely worrying mental and spiritual state of Argentine society. However, we know that this worldview also rules many other places on our planet. If we continue, everything indicates that nothing but mutilation awaits us.

4. Metamorphosis of a body

The matter of which I´m made has nothing purely present.

I transport ancestral past and am destined for the unimaginable future.17

I thought it was necessary to delve into the sociohistorical dimension of my country, Argentina, to open some paths and build precarious bridges that would allow readers and artist-researchers from other places to come and go, enter and leave, and weave our stories into a shared history. Metamorphosis is a force that allows living things to unfold in a plurality of forms simultaneously and successively, and it connects those forms, allowing them to pass into one another (Coccia, 2021).

Similar to how the Ballena Project's Artistic Research Grants were triggered by the neologism E/earth (T/tierra)18, which proposes simultaneously inhabiting and feel-thinking the macro and micro spatial scales of our existence on Earth, I consider it pertinent to think that situated artistic research is drifting towards new onto-epistemic paradigms. In this sense, the local and global dimensions of our histories undergo a metamorphosis. This presents a challenge to our modes of artistic research. What time are we inhabiting today? Whose time? What temporal coordinates are of interest to our artistic research?

It´s also necessary to understand whether our artistic research “opens or closes the door to otherness”19. Do our works allow us to reveal and deconstruct processes of subjectivation that naturalize inequalities and exclusions? Or do they reproduce and recreate experiences of violence and domination? In this regard, it´s also worth asking if situated artistic research practices are sensitive, giving rise to new alliances and opening themselves to new knowledge from new human and non-human actors.

Finally, from my artistic, pedagogical, research, and activist practices focused on the visual arts—although the question applies to all artistic disciplines—it is urgent to ask ourselves about the role and power of symbols, imaginaries, and poetics created from our corporealities within the dispute against the machinery of annihilation of diverse life forms. I believe that we can counteract and deactivate the mutilating violence of the terricidal chainsaw through a sensitive offensive: community-based artistic research that detects, creates, transports, and shares constellated, living knowledge.

Eduardo Molinari, May 23rd, 2025.

Bibliography

González, Valeria Roberta; Molinari, Eduardo (2023) Becas a la Investigación Artística. Proyecto Ballena, Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, Buenos Aires.

Calderón, Natalia; Cervantes, Abel; Salazar Atzin (2022) Saberes vivos en la investigación artística. SPIA, Instituto de Artes Plásticas, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa.

Coccia, Emanuele (2021) Metamorfosis. Cactus, Buenos Aires.

Pérez, Marana Eva (2022) Fantasmas en escena. Teatro y desaparición. Paidós, Buenos Aires.

López Petit, Santiago (2014) Los hijos de la noche, Bellatera, Barcelona.

Biography

Eduardo Molinari. Born, lives and works in Buenos Aires. Visual Artist. Bachelor in Visual Arts. Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Professor at the Department of Visual Arts of the Universidad Nacional de las Artes (UNA), Buenos Aires, Argentina. Walking as an aesthetic practice, research with artistic tools and methods and trans(in)disciplinary collaborations form a central part of his work. In 2001 he created the Archivo Caminante / The Walking Archive, a visual archive in progress that investigates the relationships between art, history and territories. Together with Azul Blaseotto, he is a member of the collective La Dársena_Plataforma de Pensamiento e Interacción Artística. His artwork includes drawing, collage, photography, installations in public spaces and specific sites, performance, video, texts and publications.

- 1Carrasco, Andrés. La ciencia a la intemperie. Tierra del Sur, Los hornillos, Epuyén, Barracas, 2015. P.38.

- 2I use the term ‘body-territory’ to describe the intertwining of three concepts: First, the affective and mutually nurturing relationship between humans and non-humans, stemming from Andean indigenous thought. Second, the qualities of rootedness and community-building that Rita Segato highlights in the role of women in the struggle against pedagogies of cruelty. Third, the need for a critical spatial turn, as proposed by American geographer Edward W. Soja.

- 3https://jar-online.net/es/un-campo-constelado

- 4In the words of its creators, the Whale Project "is a public cultural policy whose first edition took place in 2020. It was a space for dialogue and a laboratory for reflection, open to all, that brought together diverse voices and conflicting ideas. It was also an attempt to think about the current times and those to come in an era marked by uncertainty."

- 5https://palaciolibertad.gob.ar/becas-a-la-investigacion-artistica-proyecto-ballena/15971/

- 6Speech by General Ibérico Saint Jean, Governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, 1977.

- 7Segato, Rita. Contra-pedagogías de la crueldad. Prometeo, Buenos Aires, 2018. P.79

- 8Facundo o Civilización y Barbarie en las pampas argentinas is the title of the book written by Domingo F. Sarmiento during his second exile in Chile. Published in 1845, it recounts the life of the federal caudillo Facundo Quiroga, Governor of the province of La Rioja, and analyzes the aforementioned antinomy. English review: https://content.ucpress.edu/title/9780520239807/9780520239807_intro.pdf

- 9https://www.comisionporlamemoria.org/archivos/jovenesymemoria/volumen13/docs/1-arte-y-politica/Texto%204.pdf

- 10https://grupodeartecallejero.wordpress.com/

- 11Ig @etceteraarchivo

- 12Dictatorships occurred during the following years: 1930-1932 / 1943-1946 / 1955-1958 / 1962-1963 /

- 13Between 2008 and 2010 I conducted an artistic research on the effects of soybean production in Argentina. The results were part of the exhibition "Principio Potosí. How can we sing the song of the Lord in an alien land?", curated by Alice Creischer, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz and Andreas Siekmann. Here you can consult the publication that was part of my installation "The soy children": https://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/soychildren-web.pdf

- 14https://contrahegemoniaweb.com.ar/2022/09/30/entrevista-a-movimiento-de-mujeres-y-diversidades-indigenas-por-el-buen-vivir/

- 15Milei, Javier. President of Arrgentina, 6.6.2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=INeuEL8vtCU

- 16Svampa, Maristella. El consenso de los commodities y lenguajes de valoración en América Latina. Ver:

- 17Coccia, Emanuele. Metamorfosis. Cactus, Buenos Aires, 2021. P.21

- 18Molinari, Eduardo: https://jar-online.net/es/un-campo-constelado

- 19https://periodicoscientificos.ufmt.br/ojs/index.php/educacaopublica/article/view/17440/13858