There is a story in Greek mythology of a man named Theseus. Theseus became a hero when he ventured into the dark corridors of the labyrinth to hunt and kill the part bull/part man monster residing at its core—the Minotaur. All he had to find his way back was a ball of red thread he carried into the maze. This past December we used similar metaphors to introduce the idea of artistic research (AR) to the participants of our cozy salon in south Tel Aviv. The Hebrew title of our presentation read, more or less: “Artistic Research: how does one describe this strange beast?”. But alluding to Lesage’s1 provocation, the real problem we found ourselves tackling was not a monster, but rather the culture of implicit fear of its very existence. In other words, the problem was the labyrinth.

Israel's art and design academia is a stranger kind of maze, defined more by few crooked narrow invisible paths than by rigid convoluted hierarchical bureaucracy. It is the lack of options, not the rigidness of its process, which get you unexpectedly stuck in dead ends. Whereas today in many parts of the world artistic research is an integral part of postgraduate art education, in Israel it is practically nonexistent. The exceptions are some random additions to curricula, mostly led by the few scholars who return to the country after having completed their doctorate in this field abroad. Even the legitimacy of this field is heavily contested. In fact, the coupling of the words “art” and “research” would pit scholars and practitioners against one another in a bloody dispute.

This is why we felt that a rewriting or even reversal of the myth was strongly needed. Whereas the rest of Israel’s academia still saw in AR a ghastly chimera, we sought out to show that they’re needlessly taking stabs at a defenseless animal. But we also saw potential in its empowerment. Reducing its image to that of a beat-up teddy bear with threads showing at the seams would defy the purpose all the same. Instead, we hoped that if we lock on, embrace and coddle it properly, AR in Israel, too, would eventually show some teeth and bite back at its captors.

1. Snack and bait

There’s a saying in Hebrew: “words engender reality.” We were indeed set on building a platform from scratch, which would give artistic researchers the much-needed freedom to develop their ideas in a friendly environment. But emancipation also requires some self-discipline; some wild animals need to first be tamed a little to establish proper trust among their peers. In other words, we needed to lure our crowd in, which is why we were also great believers in the motto: “Want people’s attention? Give them something to munch on.”

Getting the right group of practitioners and scholars together in a room had been an idea of ours for a long time. Gabriel S Moses had first tried to host an offshoot public event on AR, but it only culminated in a short-lived confused and heated debate. It was clear that such a setting wouldn’t suffice. We needed tangible incentives, beyond good intentions. We wanted to give AR more than just a conceptual home. And so started our pursuit after a permanent abode to set up the buffet.

Initially, we thought of following the tradition of a classic salon where meetings would be hosted in our living room. But since we lived in a five-roommate apartment at the time, this idea soon fell through. One cultural center showed interest but was in the midst of relocation and would take too long to offer a vacancy—not unlike any other hyper metropolis; Tel Aviv’s alternative scene tends to offer very precarious conditions. This is where Dvir Cohen-Kedar comes in. Dvir is one of the founding members of the Alfred collective who runs a well-kept showroom and studio space downtown.2 An enthusiastic artist and scholar himself, Dvir was quick to approve and offer our rogue stray critter a permanent shelter at Alfred.

2. Picking up the threaded trail

The Tel Aviv Salon for Artistic Research took off in the autumn of 2018 and structured itself step by step as we went along. Quite unintentionally, the first two sessions ended up serving as a chaotic “experimental prelude.” They took longer to convene and were marked by a looser make-up of participants keen on confronting one another, in a way that hindered the conversation. The subsequent sessions already consisted of a steadier crowd and were much better planned. The sessions were announced on a monthly basis, always taking place on Saturday evenings at 7 PM, each meeting featuring one or two guest speakers from various fields. To facilitate the formation of a community, each meeting included time for mingling over some snackbait and a concluding discussion following each presentation. To further formalize the setting, we also opened a transparent mailing-list.

Year one eventually spanned over a total of seven sessions, concluding in June 2019. At its end, a dedicated community indeed formed. However, this was not at all an easy pursuit. When we first journeyed off, our main challenge aside from structural concerns, was that few had the proper context to grasp what the heck we were talking about. Few actually studied in AR programs. And so even though our guests were practically cherry-picked, all coming from the otherwise brethren faculties of art, design, cultural studies and the humanities, the dispute was unavoidable.

Another complexity which we gave too little thought to at first, was the initial entanglement of our discussion on AR with that of digital-based art—in itself a marginalized field in the Israeli art landscape. It also didn’t help that many of the salons first invitees were previous regular attendees of the Nu-Media salon which had disbanded shortly before.

This became very apparent at the first session. Gabriel had invited Tsila Hassine to present her practiced based Ph.D. which she is currently pursuing at the Paris-Sorbonne University. Tsila’s project intersects art history and artistic practices with the technology and the discourse on the Internet Of Things (IOT). It was chosen as a starter not only because it was explicitly certified AR in an academic context. It also served as a fascinating example of the relevance of AR for various discourses existing within and without the contemporary and academic art discourse. The thematic framework of the Ph.D. takes off from a review of the role of the still object within the history of art, from the ancient and classical Western epochs and throughout Modernism and contemporary culture. Focused on the ongoing evolution of concepts such as Still Life and the Readymade Object, Tsila charts a trajectory in which the focus is constantly shifted towards the still object, whose significance in the cultural discourse is growing imbued in conceptual social and political contexts. In direct continuation of this thread, Tsila then demonstrates through her practice as an artist, how an even further evolution of the art-object is now made possible through contemporary “smart objects”. By connecting the works in her exhibitions to heat and light sensors, she transforms “still” existing art objects into “smart” art objects that can interact with their own environment. Each work reacts differently to the collected data, according to assigned “personality traits.” In this way, art objects are granted unprecedented agency, and possibly even “subjecthood.” Tsila’s transposition of IOT logics onto art is also meant allegorically, as a critical thought experiment, pointing at the wider and possibly disturbing potential of quantification and data-layering technologies to shape and control sentience and cognition.

The responses from those of us savvy in the intersecting fields of Tsila’s project were indeed very positive. However, for those of us who were newcomers to some of the discourses it addressed, Tsila’s innovative methodology proved too unique and multifaceted to serve them as a clear introduction to AR.

And so, the result ended up as a mishmash of incompatible conversations, which once again, quickly escalated into an argument. The usual conservative claims were rehashed: “Thank you Tsila, this indeed seems like a wonderfully creative exploration but in which way is it applicable as scientific research?” rebutted with “Define applicable, define scientific research, Sir! Why should your academic discipline enforce its definition?” then retaliated with “Because art practice which meshes with academic research never leads to any constructive results!”, or “Art messes up the questions that academic research attempts to answer” and so on and so on.

3. Lock on target - I want it alive

The tensions which marked the Salon’s first encounters were eventually resolved by a more robust curation of its program than we originally had in mind. This was carried out threefold:

Aside from the formal structuring of the subsequent sessions—as laid out in the opening paragraph of part two—the salon would now assume a slightly more didactic thematic stance. Instead of a free-form discussion around the presented guest projects, they would now each serve as particular case studies of the fundamentals of AR, on the one hand, vis-à-vis the field’s literary canon. On the other hand, the salon would also expand beyond the exclusive academically framed boundaries of AR, to include design as well as broader applications of practice-based and led forms of research (PBLR).

This expansion resulted in a steadier, yet altogether different make-up of attendees, coming from a much wider array of disciplines and practices. This also meant, even more than before, that we couldn’t insist that everybody accept the fundamentals of any PBLR approach or discourse as a given. But we had very limited time in each monthly session to overcome these discursive impasses, and we risked scaring people off with homework reading assignments. Instead, we simply kept putting one key question out there: where does practice meet research inside and outside of academia? To answer this question properly the sessions ended up being divided in two.

One strand of sessions introduced particular PBLR approaches in various art and design disciplines—all of which have been hardly represented in Israel to date. These included presentations by Shani Avni, on her Masters in typeface research (University of Reading); Maayan Zadka, mainly on her doctorate in sound art and studies,(University of California, Santa Cruz) and Maya Offir Magnat and Lilach Dekel-Avneri, on their work in performance studies in Israel.

The other strand of sessions addressed particular counterpoints relating to PBLR approaches. The goal of these sessions was to increase the visibility of the less expected yet altogether significant role of these approaches in the academic landscape.

“From the personalized to the scholarly and back”, for instance, was the title given to a session intended to demonstrate how PBLR can serve as a bridge between different disciplines. The session mirrored two supposedly opposite art-based methodologies in altogether separate fields. Both, however, used AR to establish personalized perspectives which drove the research to its necessary conclusion:

Nitzan Chelouche Master’s thesis was carried out at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The thesis offers a reading of the permanent installations of the Documenta in Kassel as a palimpsest-like evolution from artworks to monuments. Her project could be described as a “top-down” approach. Although her research began as a broad survey of the literature on the Documenta, and although it hinged on the scholarship of public memory and art, Nitzan’s data was eventually all collected on the ground and then coded, based on her personalized exploratory route, as a visitor inside the Documenta herself. Through her eyes, a hidden permanent exhibition within the exhibition of the Documenta was revealed and interpreted in the particular historical context she had charted on her way.

Meeting her from the other way round was Asaf Oren’s Master’s project, “Zerrissen” (torn), which he carried out at the Berlin University of the Arts. Asaf’s project is designed from the bottom up. Rooted at its center is Asaf’s mourning experience over the death of his mother, and the tension which he had felt form between his personal grieving process and the rigid protocol of Jewish customs which his family was expected to follow. To resolve this tension, Asaf then looked outbound. He further contextualized his personal history, beyond its ethnic link to Judaism by exploring the influence of his Western upbringing on his personal mourning experience, and sought the help of its wider scholarship on mourning practices. This part of his exploration started with the Jaws T-shirt he had worn for the Jewish tearing ceremony on the day of his mother’s death and ended with Douglas Crimp’s comments on public mourning as a form of protest, resistance and empowerment during the aids epidemic in the US.

Nitzan and Asaf’s works eventually came full circle, each according to the criteria of his or her discipline. Nitzan’s personal exploration was eventually submitted as an academically styled thesis whereas Asaf’s scholarly pursuit culminated in an art exhibition, whose work process was documented and reflected on. Still, both projects bore similarities in their ability to weave previously unaddressed cultural contexts through the thread of the researcher’s personalized engagement and practices. The spectrum which we now opened by pairing these two projects was meant to help our salon-goers find their place, no matter how distant the fields that they are active in.

An altogether different conversation on the place and role of artistic research, in this case particularly in Israel, was held in our concluding session for year one, titled “Visibility and Feasibility: Between Research, Institution and Establishment.” In it, we tackled the problem of the limited framework available for PBLR in Israel. Udi Edelman was invited as the founder of the Institute for Public Presence within the Center for Digital Art in Holon, to share a chair with Dr. Yoav Friedman, Head of the Research and Innovation Authority at Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. Udi is an artistic director keen on AR, whereas Yoav acquired his administrative position following his rigorous study of EU and globalization-based higher education policies. Seating the two together gave us a much clearer picture of the conjuncture which defines PBLR in Israel today. This also helped clarify, in a way, why our AR Salon is unique in the structural discursive platform it offers. We were confronted with two models:

The first was that of the independent art curator, in this case Udi, who embraces AR in his very personalized interpretation and implementation of it. The Center for Digital Art in Holon definitely helps introduce the broader international discourse on AR,3 but the Center’s main investment seems to lie more in the use of art-based research for the curatorial purposes of its own shows. Yoav, on his side, presented the current general administrative approach towards PBLR in Israel. In his presentation, he charted a narrow yet solid path for possible funding, according to specific market and industry needs—with his orientation mainly towards design, not art. Here too, however, there seems to be given very little room for scholars’ and practitioners’ personal projects, engaged in reflection and contribution to their research field per se. The main emphasis in Yoav’s presented model is put on the applicability of PBLR approaches at the service of other fields, namely science. Incentive is given to scientific project which bring artists and designers on board to help science tackle problems “creatively”; to use product-oriented practical approaches as a glue, to bridge the chasm between basic and applied scientific forms research.

Conclusion: Theseus’s pet

As of today, there still exists no robust institutional framework PBLR in Israel’s higher education system. Some programs do offer an introduction to these approaches, mostly in one-off events, supplementary courses or the possibility to submit PBLR projects. Some scholars manage to squeeze in PBLR project under the guise of a niche within the niche of more established, mainly product-oriented programs for design and architecture. Either way, the vocabulary mainly seems to be that of pragmatism; practical knowledge applied where applicable and an extension of the student’s main toolkit. Outside and beyond graduate-level academic studies, certain prospects do exist, as presented in the concluding session of the salon. Still, as appealing as these prospects may seem, financially, they underscored the stark feeling of displacement of PBLR in Israel. To put it in prose, to do AR in Israel, you can either run your own institute with your own shows or you can resort to teleological, utilitarian persuasions of the science community on how to help them alleviate problems like the climate crisis with your extensive knowledge in organic based-pottery.

Perhaps it is the strong leaning by Israel’s economy on technological innovation. Perhaps it is its exclusion from the conjunctures and shifts in higher education which helped establish the field worldwide—such as the Bologna process in the EU. The focus in Israel remains on introducing art and design based approaches, under suspicion, as a possibly efficient addition; not as a vibrant discourse existing in its own right. In that sense, as marginal as our endeavor might be, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that the Tel Aviv Salon for Artistic Research remains the only Israeli forum explicitly dedicated to the field.

It is important for us, however, to end this piece on a positive note. As the first year concluded, it was no surprise to us when the vibe in the room pointed to a definite ‘yes’ regarding a possible second year. Granted, things didn’t go as originally planned. What began as an attempt to form a community of explicitly artistic researchers, reshaped itself into a dedicated curious interdisciplinary group of practitioners and scholars who finally found a place to have a much-needed conversation—one they couldn’t name, yet all felt they desperately lacked.

This conversation is far from over.

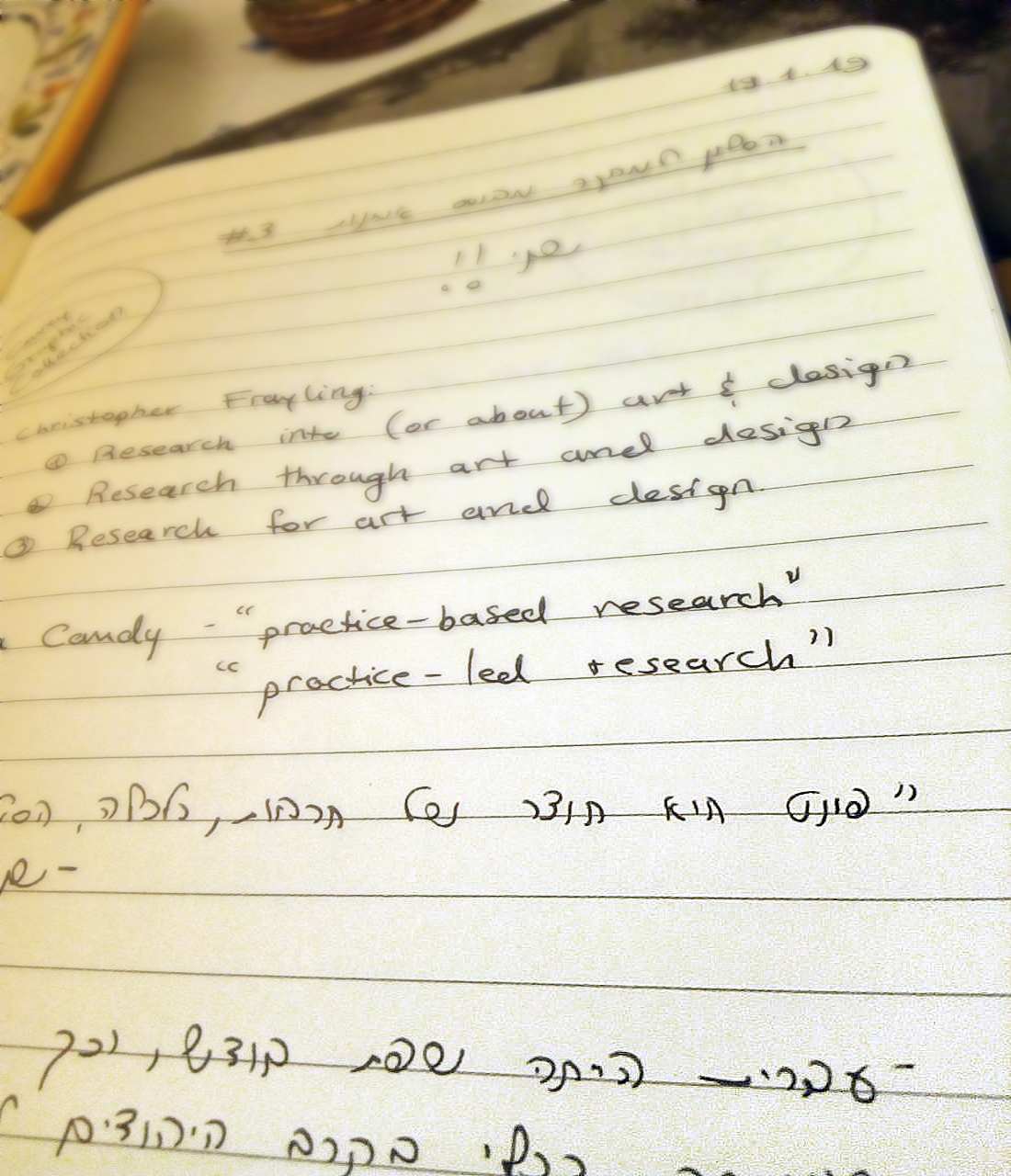

For the coming year, set to launch Nov 30th, a long list of potential speakers has been jotted down in our notebook. Building on last year’s foundation more scholars and practitioners are now invited to introduce their work and to help expand our tight-knit community. The number of Israeli students in AR programs abroad is growing and we would love to invite them to contribute their bricks and mortar to this grassroots establishment.

Some houses need work. They might come without a roof, or have creaky staircases and crooked twisted corridors. But when tearing down your house is not an option, best work on one good corner. Make one spot inside the maze feel like home and hopefully you can branch out to the adjacent rooms in time. In Israel’s marginalized sectors of culture and art, work starts small but ventures are pursued passionately. Remember, the shadow at the end of the hall is not a monster, it is a reliable watchdog. It is the driving creative force at the heart of it all. It is the perceptive, unique, critical pair of eyes through which the openings appear, and it only listens to you. So nurture it, build your community around it, grow by helping it grow, and when you’re tired of the road, sit, share a snack and it will snuggle up with you.

* This text was updated on Jan 6, 2020, to adjust an incorrect affiliation

Biographies

Gabriel S Moses is a Leipzig based scholar and media artist with a millennial complex. In other words, he is older than he appears and he exploits it. His deceptive looks helped him publish several graphic novels in Germany (Spunk, 2010, and SUBZ, 2011) and also showcase works in Ars Electronica (Linz), transmediale (Berlin), Lenbachhaus (Munich) and FILE (Sao Paulo). In 2014, his project Enhancement won 1st prize at the "Future Storytelling" contest in HKW (Berlin). He holds a Master’s degree in artistic research from the Institute for Art in Context (UdK-Berlin). He is currently a DAAD scholar and is pursuing his PhD in artistic research at the Bauhaus University in Weimar on the boundary of performance, discourse and digital-culture studies. Since 2018 he has been co-running the Tel Aviv Salon for Artistic Research together with Nitzan Chelouche.

Nitzan Chelouche is a graphic designer and PhD candidate at the DAAD Center for German Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her interdisciplinary research examines Hebrew typography in German public space. Nitzan’s goal is to introduce epistemology and research methods familiar to designers and artists into the world of social sciences and humanities research. She enjoys revealing the wonders of typography to academic audiences. Her work has been presented at the Freie Universität Berlin, the University of Montreal and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She holds a Master’s degree (magna cum laude) in Contemporary German Studies from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a Diplom (FH) in Integrated Design from the Cologne University of Applied Sciences. Since 2018 she has been co-running the Tel Aviv Salon for Artistic Research together with Gabriel S Moses.

- 1Lesage, D., 2009. “Who’s Afraid of Artistic Research? On measuring artistic research output.” Art & Research, 2(2), pp.1-10.

- 2Alfred Cooperative Institute for Art & Culture, official website: https://www.alfredinstitute.org/eng/alfred-institute-welcome

- 3A good example was the Center’s hosting of the practice-based PhD program of the HFBK (Germany) for a session of doctoral presentations, on May 30th, 2018. Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/187868245267365/ last accessed 12.11.2019